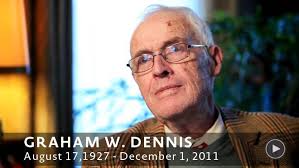

As a bitter strike at Atlantic Canada’s largest and most storied daily newspaper heads into its second year, both sides frequently invoke the memory of the Halifax Chronicle Herald’s late publisher to justify their competing arguments. But the more important question now is, will Graham Dennis’s 170-year-old newspaper even be around for anyone to remember by the time this strike ends… if it ever does?

By Stephen Kimber

Even before today’s I’ll-show-you-mine-if-you-show-me-yours, beginnings-of-bargaining dance between representatives of the Halifax Chronicle Herald and the Halifax Typographical Union, David Wilson already knew this round of contract negotiations would be the most difficult yet.

It had been 16 years since Wilson, the Ottawa-based staff representative for the Communications Workers of America (Canada) — the parent union that represents the newspaper’s 61 reporters and editors — negotiated a first contract at the Herald. That one had taken seven months. “There was pushback from management,” he recalls today, “but, at the end of the day, we got a decent deal for a first contract, and everyone was happy.”

Much had changed since then — none of it for the better for anyone.

The giant, fire-breathing, media-killing dragon in every ink-on-paper newspaper newsroom is the Internet. The entire industry is reeling, not only from over-the-cliff declines in the numbers of print subscribers, thanks to oceans of free-for-the-clicking content online, but also from the continued cratering of all forms of traditional newspaper advertising (houses, automobiles, classifieds, display, etc.), thanks to the reality sellers now have many more direct digital channels to reach their buyers.

The traditional 80-per-cent-advertising/20-per-cent subscription revenue model appears broken beyond repair, and most experts agree the future of the old printing-press, fleet-of-trucks, legacy newspaper industry — if it has one — will involve becoming more digital. The questions for those legacy publishers that no one can yet answer: how to get there? at what cost? who will pay for the news of the future and what will they be willing to pay?

In addition to those big picture woes, the Herald itself faced increasing competition for readers and advertisers in its own small market: there was Metro, a free daily that is part of the deep-pocketed Toronto-based Star Media Group; The Coast, an alternative weekly that attracts plenty of entertainment-related advertising; allnovascotia.com, the online business daily that has become the go-to source of business and political news for the local business community; and the Halifax Examiner, an ad-free online news outlet run by award-winning investigative journalist Tim Bousquet that is building readership with a mix of free and paid content.

The Herald had non-journalism-related financial issues as well. Like plenty of private companies, its defined benefit pension plan had been sideswiped by the 2008 financial meltdown. Management recently had to write a cheque for several million dollars to make things actuarily right again. Perhaps understandably, the company now wanted out of that costly, contract-mandated plan.

That said — unlike many newspaper companies across North America, which were still shuddering under the debt burden of expensive, expansive mergers and acquisitions made in earlier, headier times — the Herald had avoided at least that fiscal abyss by steadfastly remaining one of the few large independent newspapers in the country. Not that the company didn’t have significant other debt of its own: it was still paying down a $26-million “state of the art” Wifag printing press bought back in 2003.

As a private company, the Herald was under no obligation to make its finances public, of course, but it has insisted its current union contract — signed in 2011— is “unsustainable.” According to the union, however, the company’s audited financial statements — which it was later permitted to examine on a confidential basis — “showed the Chronicle Herald to be profitable.” The “potential reduction in its profitability,” according to the union’s reading, was that the newspaper had decided to write down its printing press debt faster than normal in order to make its finances look worse than they really were in order to pressure the union into more concessions.

The first official bargaining session was scheduled to take place today, October 21, 2015, in a private meeting room at Halifax’s Lord Nelson Hotel. When it began, the company handed union negotiators a copy of its 2011 contract with penciled-in changes it wanted. There were more than 1,200 changes to the non-monetary contract clauses alone! Some were mundane, but others seemed designed to slam a heavy management fist down hard on the scales of union-management balance.

Jula Hughes, a University of New Brunswick law professor who specializes in labour law, reviewed the contract for the CBC. She concluded it would change the notion of job security to “an aspiration rather than a right… I can’t tell you what would happen, but I can tell you that the employer certainly would have the ability to fundamentally move from being a unionized to a non-union workplace.”

When he first saw the company’s offer, Wilson remembers, “I said, ‘Oh my lord, look at this.’ If we accept this, we’ll be a union in name only…. We knew this would be tough, and we knew we would have to be concessionary. But…”

He tried to be optimistic. Without strikes, or public rancour, the union had recently struck deals with other newspaper owners, occasionally even achieving modest salary increases. Wilson himself negotiated contracts with all three New Brunswick dailies. In Saint John, he says, “we reached a deal in one hour and 24 minutes. With the Irvings!”

And yet he knew relations between Herald management and the union had been deteriorating for at least a decade. Each of the last three sets of contract negotiations had become more fraught. In 2009, the company laid off a quarter of its 100-journalist newsroom; in 2014 another 17 had been lopped through layoffs, buyouts and early retirements. In the winter of 2015, the company locked out its small pressmen’s local after those members had rejected company proposals to decimate their pension plan. The pressmen were quickly — and some said brutally — brought to heel in a way many in the journalists’ union saw as a dry run for company plans to do the same to them in this set of negotiations.

To complicate matters for everyone, Graham Dennis, the paper’s longtime owner and publisher who’d helped make the Herald one of Canada’s most successful independent newspapers, had died in 2011. Dennis, who didn’t want the bad publicity he knew would result from having his employees on a picket line in front of the Herald building, had often apparently intervened to short-circuit near-strikes during previous rounds of negotiations by instructing his negotiators: “get it solved.”

Mark Lever (Halifax Examiner)

He’d now been replaced as publisher by his daughter, Sarah, and — more worrying to the newsroom — her new husband, Mark Lever. He had become the company CEO in 2012. As the union was quick to point out, Lever knew nothing about newspapers and his own relatively skimpy business resumé included two bankruptcies. Lever had spoken hopefully of re-inventing the Herald as a new and different digital-based entity “with all the complexities and risks this transition entails.” That re-invention would be easier, it went without saying, if the company didn’t have to deal with a pesky union.

Lever was not at the negotiating table today. Neither was Sarah Dennis. In fact, Wilson had never met Lever and only encountered Sarah once, in passing, at the time of the signing of the 1999 contract. But Wilson certainly knew the Herald’s designated negotiator: Grant Machum, a Halifax-based management lawyer and partner at Stewart McKelvey, whose web page boasted he had been “successfully advising employers on operating union free for over 20 years.”

Machum’s starting position was clear. It was also, he told them, his ending position. Although the newspaper would go through the bargaining process — including conciliation, if necessary — it would not change its offer. The union, he told Wilson, could accept what was offered, or “you’ll be in the snowbank in January.”

“Graham Dennis,” he added is his opening comments to the full union negotiating team, “isn’t around to save you anymore.”

For the record, Machum says “the words attributed to me are not correct,” but the larger record is also clear. Before January ended, the paper’s reporters and editors were in the snowbank, even after the union had put what it called “serious concessions on the table.” Those included:

- an immediate five per cent wage cut across the board,

- no wage increases for the first two years,

- a 25 per cent reduction in starting salaries for new reporters and photographers,

- a severance cap,

- reducing the reporters’ mileage rate by 17 per cent

- and cutting back on vacation days.

Although the union claimed its concessions would “save the Chronicle Herald and take away from bargaining unit employees millions of dollars over the life of the collective agreement,” management “rejected outright” the offer.

The journalists then voted virtually unanimously to give their union a strike mandate, but the union said it wasn’t planning to walk off the job — it was expecting to be locked out — until the company forced its hand by announcing plans to unilaterally impose its original, un-agreed-to contract proposal on the newsroom until a final deal was reached. That contract, of course, included the provisions that would have effectively gutted their union’s future bargaining power and resulted in the layoff of nearly one-third of their members.

The editors and reporters walked away from their terminals at midnight January 23, 2016, and have been on strike ever since.

Since then, there have been just two abortive attempts at bargaining — in May and November. As part of those after-last-call sessions, the union even ceded more of its existing contract, agreeing to negotiate a non-union production hub that will eliminate another dozen union jobs.

The company countered by upping the ante with new demands:

- exclude four more positions from the bargaining unit, including one occupied by the union’s vice president;

- reduce sick leave pay after 30 days;

- reduce wages by a further four per cent;

- lay off eight more employees (If you’re counting, that’s 26 layoffs, including the union’s president, plus 16 more union members removed from the bargaining unit, including the union vice president — meaning 42 of the 61 union members at the beginning of the strike would no longer be in the union.)

- To add insult to injury, the company insisted it be allowed to retain new replacement reporters and editors hired during the strike even as it was laying off its experienced union journalists.

- Finally — before it would even agree to sit down to talk in November — the company said the union would have to agree to not only close its online strike paper, ca, and turn over the website and all content created during the strike to the company, but that all union members — including those who’d lose their jobs as a result of any deal — would also have to agree to sign a “non-disparagement” of the Herald clause. Before it would talk.

After the most recent failed attempted to re-start negotiations in early November, the union — which has also unsuccessfully asked the Nova Scotia government to become involved — filed an unfair labour practices complaint with the provincial labour relations board, accusing the company of “bargaining to impasse proposals that are designed to be rejected,” and asking the board to order Herald management back to the table to actually negotiate a contract. A decision on that complaint is pending as of this writing.

And so it has gone. And keeps on going…

Which means there are still far more questions than answers about this dispute. Does Herald management really want a deal or is this strike, as the union insists, all in furtherance of the company’s larger intent to operate “union-free?” But if management does honestly want to negotiate a contract, has the bitterness this dispute has engendered rendered such a happy ending impossible? Even if the two sides can indeed put aside their differences and come to a deal, will the paper they all claim to love still have enough advertisers to pay their bills, and enough readers to write for?

And then too, of course, there is a larger, though largely symbolic, and completely unanswerable question: what would Graham Dennis really think about what is happening at the newspaper he considered a “sacred trust,” and presided over for 57 years?

The union often invokes his name, calling him the “highly respected owner of the Herald,” and suggests he would be “turning over in his grave” if he only knew what his heirs were really up to. For his part, new Herald CEO Mark Lever argued in a pre-strike letter to readers the company was simply following Graham Dennis’s dictum that maintaining the newspaper’s independence was “vitally important [and] he would want all of us at the Chronicle Herald to work toward this goal.”

As for Graham Dennis himself, he isn’t talking.

***

The first newspapering Dennis was Graham’s great uncle, William Dennis, a displaced “live-wire” Englishman who joined the Halifax Morning Herald in 1875. At the time, there were five competing dailies in Halifax, another five weeklies and even a literary fortnightly. Dennis liked the newspaper business so much he eventually bought the Herald, as well as an afternoon paper, the Evening Mail. When he died in 1920, he instructed his executors that his newspapers “shall be conducted as public utilities for All The People.”

His successor, a nephew named William Dennis was described as “a bullying, aggressive, pushy, smart businessman,” not to mention a flamboyant promoter and crafter of sensational headlines who helped transform the paper into the most read and most important newspaper in the province. By 1949, he had engineered the merger of his last remaining competitor and transformed Halifax into what would become a one-newspaper town for the next 32 years.

Just five years after those mergers, however, William died suddenly, and his son Graham William Dennis, then just 26, officially inherited his father’s mantle and monopoly.

“An eccentric, formal man, who rarely went out in public without his three-piece suit” and never quite fit the mold of the swaggering newspaper magnate, Graham Dennis became a curious, complex, enigmatic figure.

During the 1970s and eighties, the newspaper business, if not a licence to print money, came close. Annual profits of 20 and 30 per cent were not uncommon in the industry. Given the Herald’s dominance in its local monopoly market, of course, suitors lined up with offers to buy it. Graham rebuffed them all, partly because — like his great uncle — he saw Nova Scotia ownership as a “sacred trust.”

Graham himself spent freely on his newspaper’s journalism, opening bureaus across the country, as well as in London, England, and his reporters and photographers roamed the globe to cover important events from American elections to the famine in Ethiopia. The Herald itself also became a benevolently paternalistic organization where loyal employees facing personal issues could expect a helping hand. Some workers even got interest-free loans to buy their homes. Graham presided benignly over it all from his fourth floor management perch, descending to the third floor newsroom only occasionally, but always just before Christmas when he and his managing editor would personally hand out Christmas cards with bonuses inside to his reporters and editors, and offer his grateful thanks for a job well done.

That all began to change in the late 1970s after Graham hired Bill Smith, a curmudgeonly, bombastic, Trump-like figure, as his managing editor. While carrying on quixotic Dennis-supported editorial campaigns in favour of highway safety and against estate taxes on the wealthy, Smith casually reassigned, belittled, alienated and fired many of the paper’s best journalists. They, perhaps not surprisingly, called in union organizers.

But the first attempt to unionize the newspaper failed dismally. The supposed ringleaders were fired, rehired after the union filed unfair labour relations charges against the paper and then reassigned to scut duties like organizing clippings in the newspaper’s library. It would take the paper’s journalists 20 more years to work up the courage to invite union organizers back on to the premises.

By the time the Herald and its newly unionized reporters and editors did reach their first contract agreement in 1999, Graham was still in charge, but he was now 71 years old.

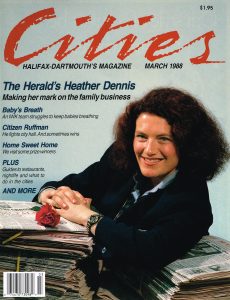

She was successful. After a Heather-supervised redesign, the newspapers’ circulation topped 148,000 (versus today’s less — some say significantly less — than 70,000), but not everyone was pleased. There were “shouting matches” between Heather and some of the paper’s middle managers, who’d liked things just the way they were, thank you very much. In 1989, Heather, frustrated, she says now, not only “by the people dad had advising him,” but also, ultimately, by her father himself, quit her job. “I saw myself as a change agent, as someone who brought together people from all departments to redesign the newspaper. My father was more of a divide-and-conquer kind of manager who would never say yes or no directly. We never had a meeting about issues. Instead, there’d be the cold shoulder, the silent treatment. You got the message.”

A decade later, Graham tried again, anointing William, his son by his second marriage, as chosen successor. But then, in 2002, just as Will was about to assume a more senior role in the newspaper, he died after complications associated with an epileptic seizure. He was only 30 years old.

Sarah Dennis (Dalhousie)

Sarah, Graham’s daughter from his second marriage, then became the reluctant heir apparent. Though she’d earned an MBA from Saint Mary’s University, tried on virtually every non-editorial job at the Herald and been named the company’s vice president in the 1990s, she didn’t feel the newspaper in her bones as her father had. In fact, Sarah insisted she would have much preferred to have shared the job with Will. Even after Will died, she wasn’t sure she would actually get the nod from her father. “You could never tell with my dad,” she told KPMG’s inBusiness in 2013, “so there were many times, up until he died, that I didn’t know if I’d be the one running it or not.”

Her father, she admitted, was not an easy man. He rarely talked to his daughter — his vice president — about the paper’s financial situation, but he would often test her to see if she’d trip up. Working for him, she explained in that 2013 interview, was like being a contestant on Survivor. “I’ve tried to bury a lot of those things back in the past.”

Soon after her father’s death, however, Sarah officially became the newspaper’s new publisher. After she married Mark Lever, she named him the company president and CEO. Despite his lack of newspaper experience or business track record, the union claims Lever’s starting salary was $12,000 a month. Employees became more irritated when — at a time management was talking poor, and demanding concessions from the union — Lever showed up in a new silver Mercedes valued at over $100,000, and he and Sarah began to take exotic vacations, including one, on strike’s eve, to Antigua.

No one outside the paper’s innermost circle, of course, knows their real working relationship — Sarah declined to be interviewed, Lever did not reply to requests — but it is clear Sarah’s view of the role of her newspaper is different than her father’s sense of it as sacred trust. “It’s a business,” she told inBusiness. “You have to run it like a business. The history is important but you can’t let that dictate what you do.”

***

But perhaps because the Chronicle Herald has been Nova Scotia’s “newspaper of record” for longer than most Nova Scotians have been alive, or perhaps because, traditionally, newspapers have been central to our notions of democracy and informed citizen decision-making, this dispute between one newspaper’s owners and the reporters and editors who re-create it daily, seems both more important and also more personal than most labour disputes.

Some longtime readers have cancelled their subscriptions in protest. (No one knows how many; the union speculates the number could be as high as 10,000; the company won’t release numbers.) Some readers — again there are no numbers — have threatened to boycott companies that continue to advertise in the paper. While some advertisers have stopped placing ads, others have hung in. Members of the local arts community recently staged a press conference to complain about the strike’s impact on attendance at cultural events. The dispute has even split the Dennis family itself; while Sarah and her husband run the newspaper, her half-sister Heather has become a public champion of the striking reporters and editors.

Despite it all, David Wilson, the union negotiator, refuses to give up hope. Although he now lives in Ottawa, Wilson recalls he grew up in Halifax and delivered the Chronicle Herald as a kid. “I know how important the paper has been to the community.” He knows too that solutions take time. How long? He notes pointedly that union members at Saint John radio stations CFBC, K-100 and Kool 98 spent two years on the picket line before finally winning a new four-year contract with wage increases and job security in May 2014.

No one wants this dispute to go on that long.

“For everyone’s sake,” as prominent Halifax stockbroker and musician Denis Ryan lamented in a recent opinion piece for LocalXpress.ca, the strikers’ online newspaper, “the strike needs to end… We need our democracy back.”

Originally published in Atlantic Business Magazine, January-February 2017

Sidebar: “Portrait of a picketer“

Related Stories:

- “Mark Never, Grant Machum and Graham Dennis isn’t around to save you anymore” — Halifax Examiner

- “The Publisher’s Daughter” — Cities Magazine

- “Victims of the Herald” — The Coast

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books