There must have been a storm, but it has passed. Nothing remains but a yawning silent void, a mist-shrouded, blue-black-grey sea that extends to the horizon in all directions—to the beginning of sky, to the end of hope. She scans the mirror of flat-calm water, pocked here and there by scattered bits of flotsam—mismatched planks and pieces of metal, broken hunks of white Styrofoam, multi-patched inner tubes, forty-five-gallon steel barrels, a tattered bedsheet sail still snagged by one corner to its mast.

She knew Roberto and his cousin Delfín had been building a raft inside his uncle’s shed out of those very same pieces. It was supposed to be a secret. But everyone knew. The neighbours would come to watch, and gossip. No one told the authorities. Sometimes, other men offered a hand with the construction.

Alex had offered. Why are you helping them? Mariela had asked her husband.

Roberto’s my friend, that’s all. She’d believed him. She’d been wrong. About that. And much more.

Now, the bloated bodies finally sharpen into her focus among the remnants of the raft. They are all face down in the water, their arms and legs akimbo in a kind of studied repose, as if they’d been snorkeling and come upon a particularly beautiful expanse of coral. She can’t see their faces, but she recognizes Alex’s balding head, burned red now by the sun. How long had they been at sea? How far had they gotten? How close had they come?

She senses movement, a sound, an intense whooshing, like something breaking the surface of the water, breaking the silence, just beside her or maybe behind her, somewhere beyond her field of vision. She turns toward the sound. He bubbles up out of that still sea, a tiny head turning toward her, smiling. Tonito! Tonito is alive! He shakes his little head like a puppy, water flying away from his hair in slow motion. His hair is a raven’s black like hers. He will be such a handsome man one day. She watches those tiny droplets fly through the air, feels them splash her face. She opens her mouth, tastes the saltiness. As soon as Tonito sees her, he smiles his big, goofy, gap-toothed smile.

“Mami!” he yells, delighted but not delirious like her, as if this was any other day, as if she had just arrived home from work and he was waiting by the door to greet her. She flings open her arms, reaches out to embrace him, and…

She awoke with a start, twisted up in her bed sheet, clammy with sweat. Alone. Still. The electricity must have gone out overnight. The fan had stopped working. The alarm had not sounded. She did not want to get up, to endure the cold dribble of the broken shower, to navigate her way past the broken elevator, climb down that makeshift ladder into the blackened stairwell and out into a morning that didn’t know and didn’t care.

She wanted only to curl back into herself, to drift back into that place and time where Tonito was smiling, where she could reach out and touch him . . . to the place and time that had never been.

&&&

Many Sadnesses

Havana 2017

Tony waits for me by his classroom door. My wiry little bundle of energy, dressed in his standard-issue kindergarten white shirt, red shorts, and blue scarf, bounces from foot to foot as if the floor beneath him is burning. While his body moves, apparently independently of his arms and legs, his eyes remain laser focused on an amused Señorita Isabella as he earnestly explains something to her in a rapid-fire Spanish I can admire but not completely comprehend.

“Ah, Señor Cooper,” his teacher interrupts when she sees me. “It is so good to see you. How are you today?” She says each word precisely, carefully. She likes to practise her English on me. I try not to betray my continuing ignorance of Spanish to her.

“Estoy bien. Muy bien.” Careful too. And precise, I hope.

Tony notices me then, grins, runs up, wraps his tiny arms around my leg. “Papi, papi!” he yells. “Can we go down to the sea? Count the boats?”

“If they’re there today.” Like everyone else of every age here, Tony’s favourite new game is sighting the gleaming white American cruise ships in the Bay of Havana. Last week, we spotted three. Tony doesn’t wait, just grabs me by my hand and push-pulls me toward our destination. I shrug my goodbyes back toward Señorita Isabella, who smiles and waves.

This is our time, his and mine, but mostly his. While Tony is in school, I take care of the daily business of our casa. After the guests have departed and the rooms are re-set for the next guests, I head over to the Parque Central hotel, settle into my favourite couch in the lobby, order my second cafecito, and respond to email inquiries from potential guests. When I have finished my duty correspondence, I check the news sites. Once a newspaper editor, always . . . The internet is still painfully slow here, but faster than when I arrived. I don’t linger, not just because connectivity still costs by the hour, but also because the news is never good, and it mostly just repeats itself. Besides, I have better things to do with my afternoons now. Like spend them with Tony.

“Papi, you know Olaf?” I do know Olaf. How could I not? Tony and I watch Frozen at least once a week, more often so long as he promises not to tell his mother. I don’t like the movie because it takes me inside places in my head I don’t want to know. But Tony loves it, and I love Tony. And that’s enough. We discovered Frozen last year on a Paquete Semanal, the thumb drive filled with Hollywood movies and popular TV series a courier hand-delivers to our door each week. The packet is illegal but, as I’ve learned in Cuba, “No one cares . . . unless they do.”

For reasons that make no sense to me—we are in sunny, never-snow Cuba, after all—Tony has become obsessed with Olaf, the snowman character in the Disney movie. “Olaf is made of snow, right Papi?”

“Right.”

“What’s snow made of?”

Suddenly and for no reason, a memory I try to keep flash-frozen inside my head flashes hot and flares in front of my eyes. It’s my father, his face bloated, mottled, and blue-ish, covered by the lightest dusting of snow, staring up at me through dead eyes. Imagined? Real? I force myself not to tighten my grip on Tony’s delicate hand.

“Water,” I tell him. “Think of raindrops. Imagine the drops get so cold they turn white and stick together. Like Olaf.”

“I like water. Papi, do you like water?”

Water never used to terrify me. I grew up in a harbour city. Now I live in another one, on an island, and I’ve become an aquaphobe. Was that Mariela’s doing? Or the stories I have invented to replace the ones Dad never told me? No matter. I must not pass my panic on to my son. I must let him create his own phobias.

“Of course I like water,” I answer. “Who doesn’t?”

We have reached the Malecón. I lift Tony up and set him down on the concrete wall overlooking the bay. His brown legs dangle over the edge. I admire his brown skin, that black hair, and, most of all, those green eyes. Where am I in Tony? Perhaps that small dimple on his chin? Perhaps not. I wrap my arm around his tiny waist, root my own feet to the sidewalk, force myself not to imagine what Mariela imagines—wading into the Bay. Deeper, deeper, deeper, gone.

There are no cruise ships today, just a few small fishing boats bobbing in the distance. On the rocks to the right of us, an old man casts his rod into the water, fishing for his supper. In the tidal pool beneath, half-a-dozen teenaged boys shout and splash and swim.

“Papi, can you learn me to swim?”

“Someday,” I tell him. “When you’re older.”

“With Mami?”

“Of course.”

“We can swim together.” No, we can’t. I will not even mention this conversation to her. Mariela still has her . . . what did David call it so many years ago? “Many sadnesses.”

***

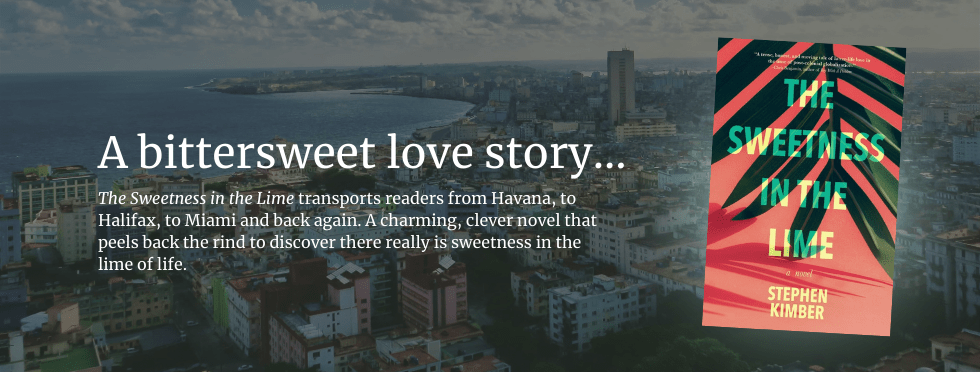

Excerpted from The Sweetness in the Lime by Stephen Kimber. Copyright 2020.

The paperback edition of The Sweetness in the Lime is available from the usual online sources, as well as the publisher, Nimbus, or your local bookstore. In Halifax, that includes Bookmark, King’s Co-op Bookstore, and Carrefour.

You can also purchase The Sweetness in the Lime as an ebook.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

THE LATEST COMMENTS