In 1978, when I was a young freelance magazine writer, Financial Post Magazine assigned me to profile Brian Mulroney. Two years earlier, Mulroney had lost his bid to lead Canada’s Progressive Conservative Party to Joe Clark and had then taken a very different job as president of Iron Ore Canada. Financial Post editors wanted me to find out what it was like to switch high-profile careers in mid-career as Mulroney had done. What followed was one of the strangest experiences of my journalism career. The story was later documented by author John Sawatsky...

(From Mulroney: The Politics of Ambition by John Sawatsky, published by MacFarlane, Walter & Ross, 1991.)

Later that spring, the Globe and Mail’s evaluation [that Mulroney’s public words of support for Joe Clark were not to be trusted] was borne out in a shockingly public manner. No matter how badly Mulroney trashed Clark in private, so far none of his bad-mouthing had ever gotten into print — for which he could thank the Montreal media, who listened to his Ritz-Carlton rants without reporting them. But all that changed in April of 1978 when Ottawa freelance journalist Stephen Kimber interviewed Mulroney on behalf of the Financial Post’s monthly, the Financial Post Magazine.

Kimber was putting together a feature profile on Mulroney. What particularly interested him was how Mulroney had switched professions in mid-career and come out on top in the business world. So, it was business and not politics that, by pre-arrangement, brought Kimber to the Chateau Lautier in Ottawa on April 11, where Mulroney had just emerged from a meeting. But instead of doing the interview in the hotel, as they had arranged, he invited Kimber to drive with him to Montreal. The two climbed into the back seat of Mulroney’s black Buick, with Joe Kovacevic at the wheel, and settled into the plush red velvet upholstery. While Kimber scribbled notes, Mulroney started to talk.

Ottawa was expecting Trudeau to call an election any day now, and that dearly was on Mulroney’s mind. He had hardly loosened his tie and lit up a cigarette when he started talking about Clark’s prospects in the coming campaign. “I look at the numbers, you know, and I just can’t see it,” Mulroney said. “God bless him if he can do it, but the way I look at it, Clark is going to get wiped out in Quebec. Without Quebec, there’s no way he can win the election.”

A great quote, but not the story Kimber had come to get. “The Liberals took a poll during the leadership convention, and it showed that with me as leader, there were only two safe Liberals on the whole island of Montreal, Trudeau and Bryce Mackasey.” Mulroney would not get off politics.

Then he launched into a description of how the “private little club” — as he called the Tory caucus in Ottawa — had conspired against him during the leadership race. On and on he went with graphic descriptions of how they had screwed him at every turn. “I can still remember after the first ballot Jim Gillies and Heward Grafftey came over and they were standing in front of me — Heward’s eyes bulging right out of his head — and they were screaming at the top of their lungs that for the good of the party I had to go to Clark. Here I was, the number two candidate, and they were telling me I had to go for number three.” Mulroney kept pouring it on while Kimber, now a somewhat frustrated note-taker, tried to squeeze in the odd question.

“You know what they called me?” Mulroney asked rhetorically. “Now, this is the unkindest cut. They said I was the candidate of big money, that I was trying to buy the leadership. I had to laugh.” He added: “It wasn’t an easy thing to go through. You work so hard, and you come so close only to have all these people gang up on you for no reason. I mean, I haven’t been a criminal or anything. If my father had been alive, all that stuff about being the money candidate would have given him a good laugh. We were broke all our lives. Anything that I’ve gotten in life, I’ve worked damned hard for.”

Once again, he repeated his well-worn claim that he was finished with politics. “I know you shouldn’t say that, but that is my decision. I can’t conceive of any circumstances that would change my mind.”

From there, he started unloading directly onto Clark, saying he himself had not run for the leadership because he needed a house and a job — a venomous dig at Clark for not having a career outside politics and for having moved into Stornoway from a tiny Ottawa apartment. “I ran because the Conservative Party needed a winner,” he added. The acid test for Clark, he declared, would be the outcome of the next election.

“Then we’ll see who’s a winner and who’s a loser.”

Why was Mulroney picking this particular moment to bare his soul to a journalist he had never met before? By now the shock of René Levesque’s victory was wearing off and the public was becoming accustomed to a separatist government in Quebec. Voters were once again starting to loathe Pierre Trudeau more than they feared Quebec sovereignty — all of which had resurrected Clark’s political standing, but he still looked like a long shot.

Another part of the reason may have been magazine lead times. Kimber’s article would not hit the stands until after a late-May election. If Clark did as badly as Mulroney figured he would, Mulroney would appear prescient in the aftermath of defeat. That was the best sense Kimber could make of it. Only later did he learn from other journalists that slamming Clark was a regular ritual for him. Actually, Mulroney’s interview was more a visceral reflex than a calculated political plot.

It was dark by the time the car reached Mulroney’s house in Westmount. Mila was home, but she was preparing to go to the symphony. Once she was gone, the Swedish housekeeper put the kids to bed, then served Mulroney and Kimber dinner while Mulroney continued venting his frustrations. “If Joe Clark wins the election, he said, tapping his plate with a fork, “I’ll eat this plate. I mean, let’s look at it. Can you see any way that he can win? Any way at all?” Through it all, Kimber scrawled notes, even during dinner.

After the meal they moved into the living room and Mulroney poured a drink for Kimber but not for himself. Kimber had noticed that he had not had a drop the entire time. Mulroney explained that he had quit drinking a while back. (In fact, this was a brief, failed attempt to go on the wagon. Not long after the Kimber interview, he was drinking as much as ever.) Every word he uttered was perfectly sober.

“The PQ wouldn’t have won that election if I was the leader,” he said. “It’s true. The Quebec people were looking for an alternative to a profoundly unpopular provincial government. I would have given them that alternative. It’s all in my platform. I can show it to you. You know who would have been the provincial Tory leader if I had been elected?” He paused for dramatic effect. “Claude Ryan, that’s who… He would have taken the job … I’m sure of it. Look at the Union Nationale and how they came back to life. With [Rodriguel Biron, for Christ’s sake. From zero to eleven seats. Imagine what would have happened if there’d been a Tory party in Quebec with a credible leader.”

After a moment, he checked himself. “Look, change that about how if I was leader the PQ victory wouldn’t have happened. I didn’t mean it the way it sounded. It’s just that the people needed a provincial federalist alternative, and the Conservative Party didn’t provide one.”

As much as Kimber had come for a business story, he was leaving with a political story, and a pretty hot one at that. However, a lot would change before the article appeared in the magazine’s June issue. The spring election that seemed like a sure thing never happened. Pierre Trudeau decided to postpone the vote despite pleadings from his backroom advisers, giving the resurging Joe Clark more time to recover in the polls, and a much better shot at winning. Realizing how bad his words would now look, Mulroney phoned Kimber in Ottawa a month later to see if he could postpone the article until after the election, saying that they could then talk again and this time he would be more open. But the Financial Post said no. Shortly before publication date, in a last attempt at damage control, Mulroney tracked Kimber down on vacation at his mother-in-law’s place in New York. “Did I seem bitter?” he asked. “I didn’t mean to seem bitter. Maybe we should talk about this some more.” But it was too late.

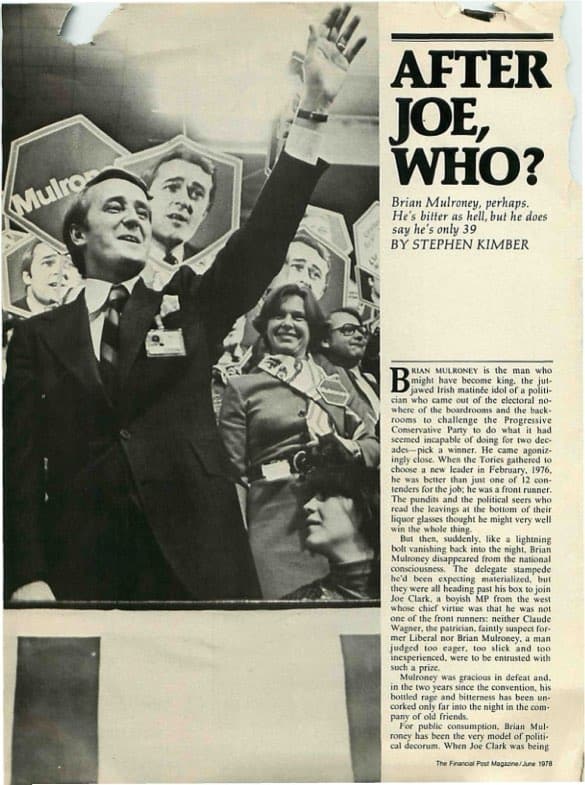

“After Joe, Who?” read the headline of the article, which answered its own question in smaller type below: “Brian Mulroney, perhaps. He’s bitter as hell, but he does say he’s only 39.” In the text, Kimber said that talking to Mulroney about the leadership convention was “like scraping sandpaper over an exposed nerve.”

During the following storm, Mulroney categorically denied making the statements quoted in the article. In fact, he went a step further and in an interview with the Montreal Star denied ever meeting Kimber. It was an astonishing claim. Yet whether anybody believed him did not matter as much as the fact that it gave him an escape. If anybody accused him of disloyalty, he had only to disown the statements. Then his accuser had to either back off or prove him a liar, which was difficult. It was a crude but effective tactic, yet it almost backfired because Mulroney had forgotten one detail that undermined his whole cover-up.

After spending the evening in Mulroney’s house in Montreal, Kimber had suddenly realized he didn’t have enough money to get back home. Mulroney had kindly come to the rescue, calling the airport and booking him on the last plane to Ottawa and putting the ticket on his own credit card. Kimber later reimbursed Mulroney, and that transaction formed irrefutable evidence that they had met.

The Montreal Star, which was checking out Mulroney’s denial that he had ever met Kimber, asked him to produce the documentary proof. But luckily for Mulroney, before Kimber could do so, the Star went on a long strike and the story died.

Mulroney would later shift his defence to the claim that the interview was off the record and that Kimber had broken a confidence, an allegation Kimber strongly denied, citing the fact he had been taking notes the whole time, including at the dinner table.

The Kimber article had finally revealed to the world just how much the leadership loss continued to torment Mulroney. He would continue to vehemently deny that he was bitter, but nobody believed him anymore. From then on, when Tories talked about Mulroney, they always mentioned the magazine article. It certainly confirmed all the rumours that had reached the ears of Joe Clark. Although Clark said nothing in public, their official relationship, already formal, became frostier still.

You can read the original Financial Post article here.

***

Although that was my only face-to-face encounter with Mulroney, I did write about him occasionally as a columnist. Here are a few of those

— Mulroney doth protest way too much (Rabble, 2008)

— Mulroney and the Money (Daily News, 2007)

—The Mulroney Institute, St. Francis Xavier University, and the honorary arms dealers (Halifax Examiner, 2017)

—Mulroney and the Media… old columns (Daily News 2000-2007)

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

Stephen, “they” always claim you are so “nasty” for listing the facts. Gerald or Brian – both sides of the house. Continued best wishes.

delightful —