From The Financial Post Magazine/June 1978

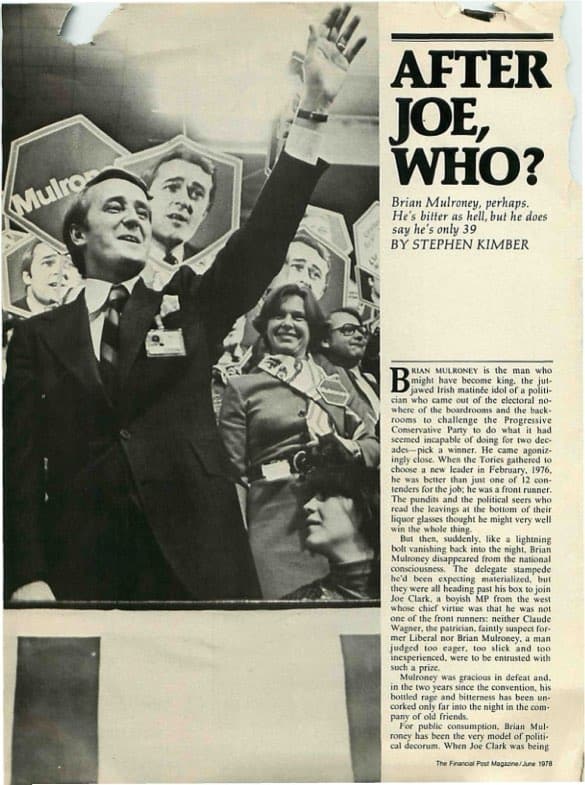

AFTER JOE, WHO?

Brian Mulroney, perhaps. He’s bitter as hell, but he does say he’s only 39

By Stephen Kimber

BRIAN MULRONEY is the man who might have become king, the jut-jawed Irish matinée idol of a politician who came out of the electoral nowhere of the boardrooms and the backrooms to challenge the Progressive Conservative Party to do what it had seemed incapable of doing for two decades — pick a winner. He came agonizingly close. When the Tories gathered to choose a new leader in February, 1976, he was better than just one of 12 contenders for the job; he was a front runner. The pundits and the political seers who read the leavings at the bottom of their liquor glasses thought he might very well win the whole thing.

But then, suddenly, like a lightning bolt vanishing back into the night, Brian Mulroney disappeared from the national consciousness. The delegate stampede he’d been expecting materialized, but they were all heading past his box to join Joe Clark, a boyish MP from the west whose chief virtue was that he was not one of the front runners: neither Claude Wagner, the patrician, faintly suspect former Liberal nor Brian Mulroney, a man judged too eager, too slick and too inexperienced, to be entrusted with such a prize.

Mulroney was gracious in defeat and, in the two years since the convention, his bottled rage and bitterness has been uncorked only far into the night in the company of old friends.

For public consumption, Brian Mulroney has been the very model of political decorum. When Joe Clark was being bludgeoned in the public opinion polls, when many Tories were sniffing around for well-paying government jobs in anticipation of even worse days to come and when the editorial writers were writing off the Conservative leader with sniping little “Joe Whos,” Brian Mulroney refused to be drawn in with the doomsayers. He was invariably polite when the reporters called, sometimes as many as a dozen of them in a single day, but he was also firm: he had nothing to say.

And yet today, the day after Jean Chretien has brought down his first budget and in the midst of all the pre-election theatrics of a parliament on the brink of dissolution, and with the Quebec Liberal party leadership about to be decided, Brian Mulroney publicly opens his emotional floodgates.

JOE KOVACEVIC, Mulroney’s Yugoslav handyman, friend and sometime driver, guides the big black Buick out of Ottawa’s Chateau Laurier garage into the stream of traffic heading east through the rain for Montreal. Mulroney slumps into the plush red velvet back seat, loosens his tie and lights a cigarette.

“I took at the numbers, you know, and I just can’t see it,” he says in his rich baritone. “God bless him if he can do it but the way I look at it, Clark is going to get wiped out in Quebec. Without Quebec, there’s no way he can win the election.”

Brian Mulroney believes he could have done better. “The Liberals took a poll during the leadership convention and it showed that with me as leader, there were only two safe Liberals on the whole island of Montreal, Trudeau and Bryce Mackasey.”

Brian Mulroney harbours not a single doubt that if he had won the leadership, he would be giving Pierre Trudeau the fight of his life. That he will never have that chance, he believes, has less to do with the campaign he ran than with the “private little club” that is the PC federal caucus.

“Did you know that I have the distinction of having had Tom Cossitt circulate a petition against me,” he says incredulously. “Cossitt actually sent around this petition to members of caucus which said they would refuse to serve under me. Can you believe that?

“I knew when I ran that not being a member of caucus was going to be the big hurdle. To overcome that, we had to work that much harder, run flatter out. But what can you do when there are 12 people running and I I of them are shooting at you.”

Michael Meighen, a former P.C, party president and an old friend views Mulroney’s bitterness this way: “Brian took a very big gamble by trying to go over the top of the party. But he went in there with the intention of going all the way and he believed up until the end that he would do it. So the result was a very, very keen disappointment for him.”

Though he believes that Clark won the convention “fair and square,” Mulroney still resents the battering he took from the other candidates. They said he was an outsider, a political neophyte.

“The fact that I had been a labour lawyer with a very successful practice, the fact that I’d served on one of the few Royal Commissions to ever actually do anything, these things meant nothing. I wasn’t a member of their private little club in Ottawa. I spent my whole life working for the Tory party, working when no one else would. Who the hell are guys like Jim Gillies and Sinc Stevens anyway? What the hell did they ever do for the party before they got elected in 1972?”

The first body blow to his hopes came during the convention when John Diefenbaker, in an ex cathedra speech to the delegates, decreed that the next party leader must have parliamentary experience. The sword was aimed straight at Mulroney. “Diefenbaker legitimized what had been a kind of whispering campaign until then. The other candidates could go around to the delegates after that and say, ‘see, Diefenbaker says it. We’ve got to stop Mulroney’.”

After the first ballot, Sinclair Stevens, considered a member of the party’s right wing, “deserted his principles” and sat with Joe Clark. The images are coming faster now, the words take on more bite. “I can still remember after the first ballot Jim Gillies and Heward Grafftey came over and they were standing in front of me — Heward’s eyes bulging right out of his head — and they were screaming at the top of their lungs that for the good of the party I had to go to Clark. Here I was the number two candidate and they were telling me I had to go for number three.”

Grafftey chuckles at Mulroney’s sniping. “I’m quite aware of the things he and his snooty friends in Montreal have been saying about me over their drinks,” he says. “But my view is that he and I just have a reasonable difference of opinion. I said then and I would say now that if you want the big job, you’ve got to be prepared to do an apprenticeship in the dirty jobs first. If he isn’t interested in that, that’s his problem.”

At 39, Brian Mulroney has taken his grab at the golden ring and missed. He says he will never try again. “I know you shouldn’t say that, but that is my decision. I can’t conceive of any circumstances that would change my mind.”

TALKING WITH Brian Mulroney about the 1976 leadership convention is like scraping sandpaper over an exposed nerve. With even the gentlest encouragement, the hurts tumble out into the open. “You know what they called me? Now this is the unkindest cut. They said I was the candidate of big money, that I was trying to buy the leadership. I had to laugh.” But Brian Mulroney is not laughing. “it wasn’t an easy thing to go through. You work so hard and you come so close only to have all these people gang up on you for no reason. I mean, I hadn’t been a criminal or anything. If my father had been alive, all that stuff about being the money candidate would have given him a good laugh. We were broke all our lives. Anything, that I’ve gotten in life, I’ve worked damned hard for.”

Despite the limousine and the company jet on standby at the Ottawa airport, Mulroney money is not old. His ancestors came to Quebec in the 1840s, poor Irish farmers on the run from the potato famine. His grandfather was a farmer, his father, Benedict Martin Mulroney, an electrician. He came to Baie Comeau, Quebec, in the 1930s for six months to help build the Quebec North Shore Paper Co. mill and never left. Brian was born there on March 20, 1939, the third of Ben’s six children.

Baie Comeau. on the shores of the St. Lawrence 250 miles north of Quebec City, is a company town not unlike the sometimes troubled company-run communities Mulroney now oversees in his role as president of the Iron Ore Co. of Canada. But the Baie Comeau of his memory remains an idyllic village of 3,000, where the houses, schools, stores and the hospital were all blessings dispensed by a paternal employer. He has no recollection, as do many French Canadians who grew up in similar circumstances, of an aloof Anglo elite which dominated its francophone employees. Perhaps that is because the Mulroneys, despite their name, felt themselves to be neither English nor French, but true Canadians bridging language and culture. “We spoke English at home and French outside,” he recalls. “I can’t honestly remember a time when I didn’t speak both languages. It seemed to me to be the natural state of affairs.”

His father toiled by day in the paper plant and moonlighted at night. What little money he could scrape together went for his passion; educating his children. All six were graduated from university, the last two financed by Brian who assumed the parental burden after his father’s death in 1965.

Ben Mulroney also believed that children should earn at least part of their own keep and so, from the age of I I until his final year of university, Brian spent his summers in Baie Comeau at a variety of jobs including several summers washing “millions of cabbage” at the local Hudson’s Bay grocery warehouse.

Since there was no high school in Baie Comeau, he was shipped off for the last years of his secondary education to a church-run boarding school in Chatham, New Brunswick, 600 miles by ferry, train and bus from home. It was, he says, “a rough experience that forced me to become self-reliant at the age of 13.”

He received his B.A. (in political science) and his first exhilarating taste of partisan politics at St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, Nova Scotia. The university was a breeding ground for public figures: among Mulroney’s contemporaries there were Robert Higgins, recently resigned leader of the New Brunswick Liberal party, Richard Cashin, a former MP and now president of the Newfoundland Fishermen, Food, and Allied Workers Union and a member of the Unity Task Force, Paul Creaghan, a retired New Brunswick cabinet minister, Gerald Doucet, former Nova Scotia education minister, and Lowell Murray, Joe Clark’s campaign manager.

It was Murray, in fact, who invited Mulroney, then a nervous young freshman, to his first Progressive Conservative meeting. Mulroney’s family were, if anything, Liberals, but by his senior year, he had become the PC prime minister in the Combined Atlantic Universities Student Parliament.

By then, he’d already attended his first national political convention-voting for John Diefenbaker in the 1956 P.C. leadership race-and had made friends with such important Tories as the new premier of Nova Scotia, Robert Stanfield.

He stayed in Nova Scotia for the first year of law school but a combination of homesickness and the desire ultimately to practice law back home in Baie Comeau convinced him to transfer to Quebec’s Laval University in 1961.

The Quiet Revolution was in its infancy when Mulroney arrived and the university, located within the walls of old Quebec City, was the perfect place for a politician-in-training to sharpen his knowledge and skills.

In his second year, he was a co-founder of the Congress on Canadian Affairs, a student group that sponsored some of the liveliest lectures and debates of the early 60s in Quebec. Though he also became president of the law society and secretary of the student association, all the while sowing the seeds of his still fondly remembered reputation as a ladies’ man, Mulroney’s growing worldliness had not sidetracked him from his basic plan to return to Baie Comeau as a lawyer.

What did eventually change his mind was an unexpected offer of a job with Ogilvy, Montgomery, Renault, Clarke and Kirkpatrick, the largest and most respected law firm in the province. His father gave his blessing. “You can come home anytime,” he said. “This is an opportunity for you.”

Mulroney made the most of it and, gradually, over the course of the next decade, he built a solid reputation as one of Quebec’s most skillful labor lawyers.

Though he represented the interests of corporate giants, his straight dealing won him the grudging respect of even his union adversaries. For that reason, he was a logical choice for the Cliche Royal Commission. Set up by the Bourassa gov ernment after a riot at the site of the James Bay hydroelectric project in 1974, the commission made Brian Mulroney, a public figure for the first time.

“Brian is a typical great Irishman,” Judge Robert Cliche remembers. “Like all politicians, he thinks a great deal of himself, which is not such a bad thing, of course. You must have ambition if you’re going to succeed, and Brian had ambition, to be sure.” Mulroney openly discussed his political plans with Cliche on a number of occasions during the two years they served together on the Royal Commission and Cliche says he wasn’t surprised in the least when Mulroney announced his candidacy.

Before and during the commission, however, Mulroney’s political activities remained very much behind the scenes. He was the P.C.’s most important backroom boy in Quebec, twisting the arms of reluctant Tory Davids to get them to take up their electoral slings against the Liberal Goliaths, putting the touch on corporate friends for campaign money, and then, when the money was spent and the slings had failed to find their mark, massaging the bruised egos so they would be willing to go through it all again. Mulroney never ran himself.

Even when his name began to turn up almost daily in the papers and his chiselled face on TV as a result of his role in the Cliche Commission, Mulroney says he didn’t fancy himself as a front-line politician. While other candidates were busily consulting admen in anticipation of the leadership race, Mulroney was on the phone to Robert Stanfield, vainly trying to convince him to stay.

The idea of trying to succeed Stanfield himself didn’t even cross his mind, he says, until the summer of 1975. Michel Cogger, another backroom Quebec Tory and a friend from Laval days, invited him to spend a day at his cottage. Over a couple of beers and under a blazing sun, Cogger laid out his views on the coming campaign. He’d drawn up a list of likely candidates for Stanfield’s job and, as they went through the list, it became obvious that none of the possibles could do what both men were convinced had to be done-win in Quebec. Until the Conservatives could make inroads there, they agreed, the party was doomed to lose.

“Then Michel said to me, ‘I have a winner,’ and I said, ‘Who?’ and he said, ‘You.’ I remember telling him to pour himself another beer because the sun must be getting to him.”

But, little by little, the notion took hold. Why not Brian Mulroney? The party and the country needed a fresh new face, someone young and bilingual who understood Quebec and who could give the voters a real alternative to Pierre Trudeau, someone who was-most importantly-a winner. Why not Brian Mulroney?

“I didn’t run for the leadership because I needed a house,” Mulroney says, taking an oblique swing at Joe Clark who moved from a small Ottawa apartment into the elegant official residence of the opposition leader after his victory. “I already had a house. And I didn’t run because I needed a job. I had a good job. I ran because the Conservative Party needed a winner.”

Despite what happened, he says he is proud of what he and his supporters accomplished. “To the extent that I’ll be a footnote in history, I’m not ashamed to have what I did judged by historians.” The acid test of the wisdom of choosing Joe Clark instead of Brian Mulroney, he believes, will be in the outcome of the 1978 election. “Then we’ll see who’s a winner and who’s a loser.”

He hasn’t totally abandoned either politics or the Conservative party, however. Joe Clark and his wife, Maureen McTeer, were recent dinner guests of the Mulroneys and he still carves out time here and there to raise some money and make the odd speech on behalf of the candidates he likes. But he will keep a low profile during the campaign.

Besides, he adds, he has enough on his plate already. Thanks notably, it would seem, to his position as president of the Iron Ore Co. of Canada.

The company had been wooing Mulroney even before his political campaign, but its job offer was just one of many which followed in the wake of the convention. “I felt . . . that it was time for something completely different and I knew a fair bit about the company and its problems. There is no denying the company has some very serious problems but I saw that as a challenge.”

The most serious and continuing difficulty lies in Mulroney’s old bailiwick, labor relations. When I interviewed him he was enmeshed in dealing with an ongoing strike against the company.

THE CAR turns off Cotes des Neiges and glides easily up the winding, tree-covered hills to Brian Mulroney’s three-story stone house on Belvedere Drive in the exclusive Montreal district of Westmount. It is a long way from Baie Comeau. “I guess I have a jaundiced view of success,” he says of the distance he has travelled. “I made a lot of money as a lawyer so money isn’t new to me. But benefits like a company jet and all that go with the job. I’m grateful for them and I would never abuse them but they have nothing to do with me. When I move on, they will go to my successor.”

Inside the rambling home which his wife Mila decorated, he takes his visitor on a tour of his collection of Canadian and Yugoslavian art. “This one,” he says, pointing to a small landscape by French Canadian painter Stanley Cosgrove, “is my favourite. It’s actually of Shawinigan but it reminds me of Baie Comeau. The colours, the greyness, are just like I remember Baie Comeau in the late afternoon in the winter.”

He searches unsuccessfully for a favourite record in the clutter of Sesame Street albums left by his children. “I’ve become more cultured since I met Mila,” he says of his pretty young wife. He was a dashing 35-year-old lawyer and Mila, the Yugoslavian-born daughter of the head of psychiatry at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal, was an 18-year-old engineering student when they first met in 1972 over a game of tennis. “Before Mila, I would never think of going to the opera or sitting through a ballet. Now I’m getting to enjoy it although I guess I still don’t understand it all that well.”

Mulroney finds time for the occasional game of tennis in the summer, but says he now gets his greatest pleasure from simply spending time with his two children, Caroline, four, and Ben, two.

With the children safely tucked into bed and Mila off to the symphony, Mulroney settles down to dinner and more political talk.

“If Joe Clark wins the election, I’ll eat this plate,” he says, tapping it with a fork. “I mean, let’s look at it. Can you see any way that he can win? Any way at all?”

A different question is intriguing me, one that has been nagging almost from the moment I stepped into the Buick in Ottawa. Why has Brian Mulroney decided to unburden himself publicly now, two years after the fact and on the precipice of the first federal election campaign conducted by the man who beat him?

“There are some things I want to say,” Mulroney answers simply, offering me a brandy. “I checked you out.”

I suspect that the real reason remains unspoken. Brian Mulroney is itchy. He reads the columnists, dissects the vagaries of the public opinion polls, talks to political friends and he senses in his gut that Pierre Trudeau can be taken. And yet … And yet Mulroney sees an electorate terrified of turning the Liberal government out because the man who would become prime minister, Joe Clark, is deemed incapable of dealing with the separatists. He can’t win Quebec. He will lose the election, the opportunity to defeat Pierre Trudeau.

Brian Mulroney is trapped in the winter of 1976, still caught up in the permutations and combinations that would have flowed from the convention if he had been chosen leader instead of Joe Clark. He needs to talk.

“The PQ wouldn’t have won that election if I was the leader,” he says suddenly. “It’s true. The Quebec people were looking for an alternative to a profoundly unpopular provincial government. I would have given them that alternative. It’s all in my platform, I can show it to you. You know who would have been the provincial Tory leader if I had been elected?” He pauses more for dramatic effect than in expectation of an answer. “Claude Ryan, [new leader of the Quebec Liberals] that’s who . . . he would have taken the job … I’m sure of it.

“Look at the Union Nationale and how they came back to life. With Biron, for Christ’s sake, From zero to eleven seats. Imagine what would have happened if there’d been a Tory party in Quebec with a credible leader.”

He thinks over what he has just said. “Look, change that about how if I was leader the PQ victory wouldn’t have happened. I didn’t mean it the way it sounded. It’s just that the people needed a provincial federalist alternative and the Conservative Party didn’t provide one.”

The conversation veers into the never-never land of what a Brian Mulroney campaign would have been like.

“There’s no doubt that I’m a conservative when it comes to recognizing the fact that the private sector is what makes this country go. Government’s job is to provide an economic climate and a tax climate that will encourage risk taking and initiative. We’ve got to stop government from seeing private enterprise as a threat. No goddamn bureaucrat ever made a country great. It was private enterprise.

On the other hand, everyone has the right to be equal and no society has ever been great if it had no compassion.”

On Quebec, Mulroney says his own views are similar to Trudeau’s “but I’m not inflexible like he is.”

BRIAN MULRONEY has turned down an offer from Joe Clark to run in this election and before and after the election of the Parti Québecois he said no to invitations from Pierre Trudeau to switch allegiances and become a Liberal cabinet minister.

He says those were easy decisions. “I didn’t run for the Conservative leadership to become Justice Minister for Pierre Trudeau and I didn’t even run so I could get a cabinet job from Joe Clark. I ran because I thought I would be a leader of the Progressive Conservative Party who could win an election.”

Mulroney pauses. “When is this story going to appear anyway? It shouldn’t go before the election. Seriously. I don’t want to sound like sour grapes about Clark, certainly not in the middle of an election campaign. The last thing I want to have happen is that someone will be able to blame me for making things worse for him.”

Five hours into unburdening himself, Mulroney seems suddenly to be having second thoughts about doing so. Brian Mulroney, the man who during the leadership campaign was considered to be an excellent manipulator of the media? “Look, if I could see the numbers in front of me — know what actually happened — there’s a lot more I could say. Why don’t you hold off until after the election? Then we’ll get together again and have another talk. Okay?”

Mulroney has clearly not chucked his political future on the discard heap. “I’m 39 now, five years, 10 years from now, who knows what I’ll be doing?”

A lot of people will be interested in the answer.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

THE LATEST COMMENTS