Allowing two RCMP officers to testify in pre-recorded sessions without the direct involvement of lawyers for the families undermines the credibility of the commission. And that’s unfortunate for all of us.

I have not watched every minute of every witnesses’ testimony at the Mass Casualty Commission. As I have with the commission’s 18-and-counting foundational documents and 1,400 itemized source materials, I’ve sampled, closely watching the testimony of witnesses I expected to offer important information, dipping in and out of others as time allowed.

Among my many impressions, I have been particularly struck by the professionalism of the lawyers, both the various commission counsel and those representing the family members and other participants.

Everyone has recognized that this is not a criminal trial, so there is no need for histrionics, or witness badgering, or carefully plotted gotcha moments to win the favour of a jury.

The goal is to ask questions that matter, get answers that help, tease out context and reflection.

That’s, in part, because the commission’s mandate is not criminal. It is to understand what really happened and why on April 18 and 19, 2020, and then produce a final report that “sets out lessons learned as well as recommendations that could help prevent and respond to similar incidents in the future.”

But it’s also, in part, because commission staff and investigators have already done much of the heavy lifting, producing a multi-sourced, minute-by-minute timeline of what happened during the 13-hour shooting spree.

Everyone, including the lawyers and the RCMP witnesses, is working from the same set of facts, the same time-coded radio transmissions, 9-1-1 calls, phone logs, interview transcripts, email trails and maps.

Perhaps partly as a result of that precise timeline reconstruction, few — no? — witnesses have so far attempted to deny the facts as laid out by the commission.

Instead, the RCMP witnesses have responded — mostly thoughtfully — to respectful questions from the lawyers. They’ve attempted to explain what they knew and didn’t know, the chaos that wasn’t captured in the timeline, what motivated this or that decision, their training and lack thereof.

Their responses have run the gamut from insistence they would do again exactly what they did that night, to bafflement at what they now know that they didn’t know then, to anger at their superiors for failures of leadership, to personal remorse for the deadly consequences of a detail missed in the moment.

Some of the Mounties and retired Mounties who testified even offered their own brutally honest assessments of their preparedness and recommendations for what needed to change to prevent such tragedies in the future.

I tell you all that because it makes the commission’s recent decision to allow some RCMP witnesses to testify via pre-recorded video, answering only questions put by the commission’s own counsel, so troubling. And potentially damaging for the credibility of a commission whose credibility has already been questioned by some of the victims’ family members.

From the outset, the Mass Casualty Commission has set out to be “trauma-informed.” Many family members — and others — believe it has been too trauma-informed, infantilizing those who lost loved ones in the tragedy and now want only answers to their many questions.

Worse, of course, for many family members, was that the National Police Federation and — worst — the Attorney General of Canada initially sought to use the commission’s trauma-informed mandate to prevent RCMP officers from having to testify at all, and then used the commission’s own Rule 43 —

If special arrangements are desired by a witness in order to facilitate their testimony, a request for accommodation shall be made to the Commission sufficiently in advance of the witness’ scheduled appearance to reasonably facilitate such requests. While the Commission will make reasonable efforts to accommodate such requests, the Commissioners retain the ultimate discretion as to whether, and to what extent, such requests will be accommodated.

— to seek special accommodations for six senior RCMP witnesses ranging “from provision of a sworn affidavit to appearing as part of a panel.”

One of those requests — one presumes the request to provide their own affidavit — was rejected. Two officers were permitted to speak as part of a panel. The participants’ lawyers offered “no objection” to any of those rulings.

In a decision released on May 24, the commission responded to requests from the three remaining officers. Based on “health information provided,” the commission agreed to allow the witnesses “to provide evidence in a way that reduces the stress and time pressure that arises from giving oral evidence.”

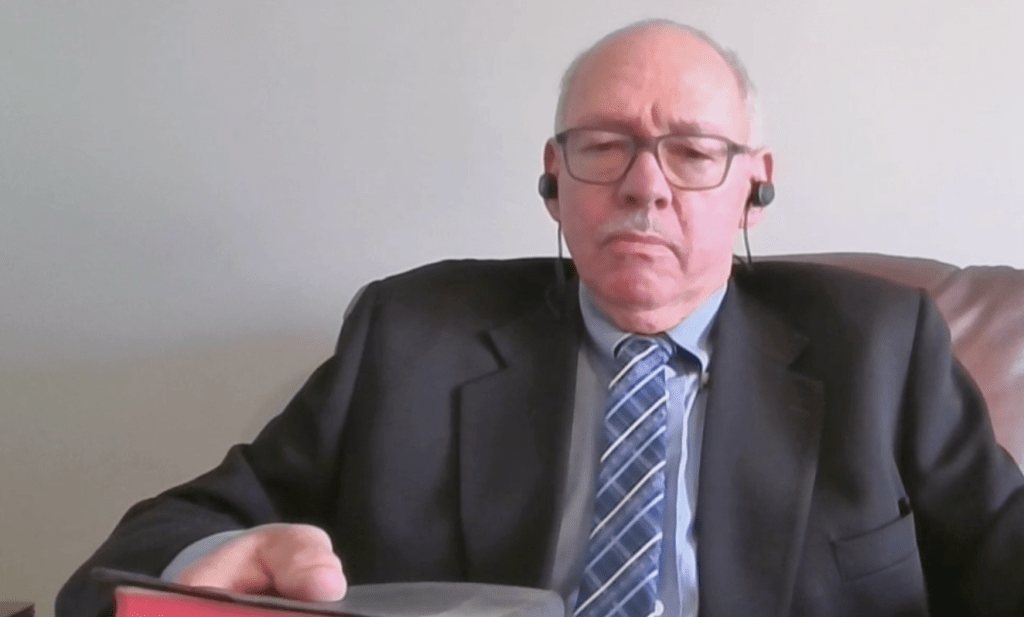

Staff Sergeant Al Carroll, who testified last week, was allowed to testify via Zoom, “with breaks as needed.”

That wasn’t a significant accommodation given that, since COVID, many trials have been conducted via Zoom.

As with most witnesses at this inquiry, lawyers for family members and other participants were still permitted to question Carroll directly.

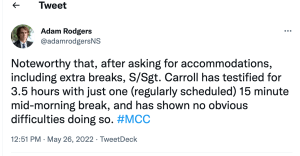

As Adam Rogers, a lawyer who has been blogging about the hearings, also noted in a Tweet: “Noteworthy that, after asking for accommodations, including extra breaks, S/Sgt. Carroll has testified for 3.5 hours with just one (regularly scheduled) 15-minute mid-morning break, and has shown no obvious difficulties doing so. #MCC”

You can find Tim Bousquet’s full take on Staff Sergeant Carroll’s actual testimony here. His conclusion:

Overall, Carroll struck me as remarkably incurious. It’s been more than two years since the terrible events he was instrumental in, and yet he hadn’t read any of the MCC documents, nor had he read any of the radio transcripts from transmissions during the events, or any other of the underlying documents that he had access to and that have now become public.

That judgement may be harsh but it is based on watching Carroll testify and interact with various lawyers.

The accommodations for Sergeant Andy O’Brien and Staff Sergeant Brian Rehill — who are scheduled to “testify” on May 30 and 31 — seem to me to be significantly more significant and problematic. They were key players in the events of April 18 and 19:

Rehill was the risk manager working out of the RCMP’s Operational Communications Centre when the first 911 calls came in from Portapique, N.S. In addition to monitoring those calls and overseeing the dispatchers, he made the very first decisions on setting up containment and where the first responding officers should go.

O’Brien was the operation’s non-commissioned officer for Colchester County at the time, meaning he was in charge of the daily operations of the Bible Hill RCMP detachment. On April 18, he helped co-ordinate the early response from home and communicate with officers on the ground.

They will each be questioned in separate pre-recorded Zoom sessions, but only by commission counsel. The only other observers allowed for their testimony will be the commissioners themselves, media, accredited participants and their counsel “who wish to attend.” Except for the commissioners, however, they will all “be off-screen with microphones muted.”

Family lawyers will be allowed to suggest questions in advance and, after the initial round of questioning, “advise of any new questions that have arisen or additional questions that could not reasonably have been anticipated.” They won’t be allowed to ask questions themselves.

Said Joshua Bryson, who represents the families of two of the victims: “That’s not a suitable replacement for meaningful participation.” He won’t be participating. “We feel that if we’re going to be marginalized to this extent, there’s really not much point in us being here to participate.”

That’s understandable.

Most of the family members of the 22 victims of the mass shooting, in fact, have instructed their lawyers not to take part in this week’s hearings as a protest against the commission’s accommodation decision.

As Nick Beaton, who lost his pregnant wife in the shooting rampage, put it: “Silence sometimes is the loudest.”

That said, this is likely the only chance for family members — through their lawyers, through commission counsel — to have their questions asked to these senior officers and, as Sandra McCulloch of Patterson Law told the CBC, “find out what exactly Rehill and O’Brien did with the information they learned during the initial Portapique response, who they shared it with, and what decisions were made by anybody as a result.”

Unfortunately, the commissioners’ emphasis on being “trauma-informed” now seems to have hobbled their search for the truth, and further undermined the families’ faith in whatever their report concludes.

It’s complicated.

As a society, we now accept that trauma — and its impacts — are real.

We recognize the devastating impact trauma can have on victims and their family members, first responders, even witnesses long after the events have receded.

But the ripple effects don’t stop there.

Consider last week’s wrenching testimony from RCMP Staff Sergeant Bruce Briers, the risk manager operating out of the Operational Control Centre in Truro. During the chaotic night that followed the first murders in Portapique, Briers missed the fact that several other Mounties, including Pictou Cst. Ian Fahie, had looked at a photo of the killer’s fake police car and noted it had a black push bar — an unusual feature — on the front.

Because Briers missed that detail and no one told him directly about it, Briers didn’t notify all RCMP officers to be on the lookout for the push bar.

Just over two hours later, an RCMP constable named Rodney Peterson passed the killer on Highway 4. It was only after Fahie radioed him directly to suggest he look for the push bar that Peterson realized who he’d seen and turned around to pursue him.

Too late. The killer went on to murder five more people.

“I have to live with that,” an emotional Briers told lawyer Josh Bryson, “and I’ve lived with that for two-plus years.”

So, yes, trauma can have an ongoing impact even on those not on the front line, decision-makers like Briers who missed a critical fact in the middle of a chaotic event and must now live with the consequences.

But Briers testified without accommodation. And we learned a lot as a result.

Which raises the Catch-22 question: How do we accommodate for trauma while getting to the truth?

When someone asks for accommodation, they often must disclose personal, private health information they don’t want shared. From the beginning, the commissioners acknowledged and accepted that.

Since witness accommodation requests involve sensitive personal health information, the Commission will not share any specific individual private information about these requests.

The problem is that the rest of us then have no way of evaluating whether the reasons were reasonable.

Instead, we are left with what else we know.

- We know that this commission has gone out of its way to make itself trauma-informed, for better and for worse.

- We know that Staff Sergeant Briers, who did not have any accommodation, testified about issues that were deeply, personally difficult.

- And we know that Staff Sergeant Carroll did not appear to need any of the accommodations he was granted.

We will not know until after the videos of O’Brien and Rehill are released whether — and how much — those accommodations may have hindered the commission’s larger search for the truth.

What we already know is that the decision to accommodate by excluding the families’ lawyers from direct witness testimony has only added to the questions about the inquiry.

And that’s unfortunate. For all of us.

***

A version of this column originally appeared in the Halifax Examiner.

To read the latest column, please subscribe.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books