Tim Houston’s in-house committee to review our outdated freedom of information legislation refuses to even meet with an outside expert group suggesting improvements. Accountability? Don’t count on it.

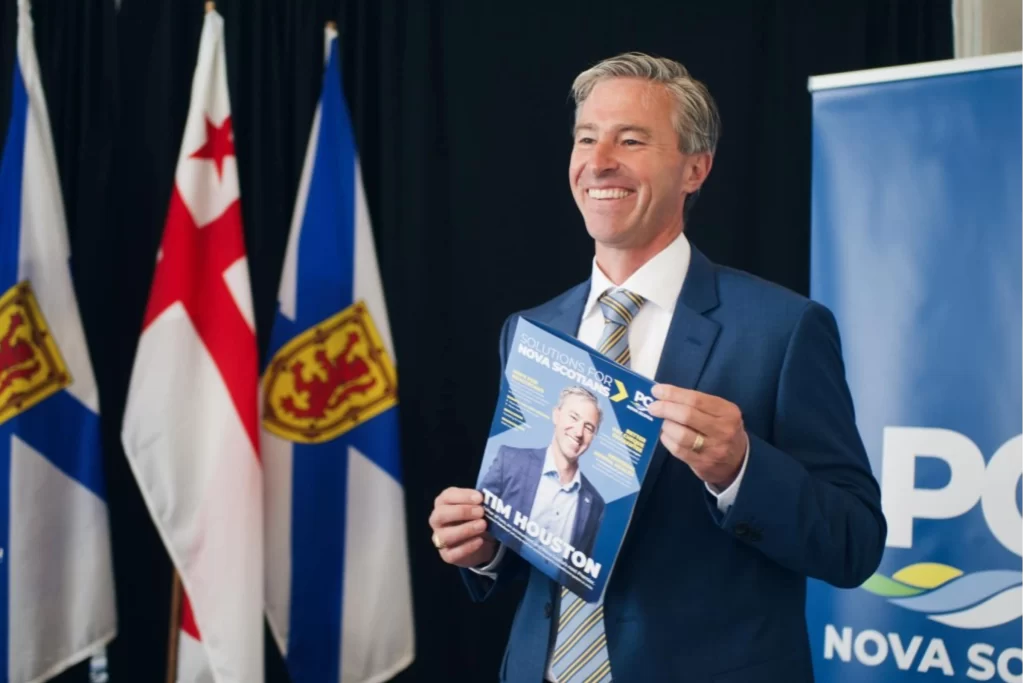

Let us begin with a return to a Better Ghost of Christmas Premiers Past — to wit, Timothy Jerome Houston, Progressive Conservative Premier in Eager Anticipation, circa August 22, 2021, five days after his party won its majority government, nine days before he was officially sworn in as the real deal.

Cue Michael Gorman, the CBC’s intrepid provincial reporter:

Premier-designate Tim Houston is poised to do something none of his predecessors were willing to do: give Nova Scotia’s privacy commissioner order-making power.

Houston, like other politicians before him, promised ahead of the provincial election that he would make the change should he and the Progressive Conservatives form power.

As the Tories prepare to be sworn in next week, Houston told CBC News on Tuesday that he’ll be keeping his promise.

There were reasons — not good reasons, in retrospect, but reasons nonetheless — to believe that Houston might possibly… may … could … perhaps be telling the truth about an issue so many others in his position had lied about so often.

That’s because Houston had his own unhappy and expensive experiences with the province’s un-freedom of information act.

On May 3, 2016, the PC caucus asked for information about the financial arrangements between Stephen McNeil’s governing Liberal government — also known as Nova Scotia taxpayers — and Bay Ferries, the company the government had contracted to operate a ferry service between Yarmouth and Maine.

The government gave the Tories a dribble of the information they’d ask for but not a word about just how much the government was paying the company to operate the ferry each year, including in years when the ferry didn’t operate.

The Tories appealed to the access to information commissioner. Two-and-a-half years later, she recommended that the government turn over information to the PC caucus it had redacted.

The government responded, Screw You, Information Commissioner, or words to that effect. “The department does not intend to make further disclosures on this file,” was the department’s actual phrasing in a dismissive letter to the information commissioner.

They could get away with that, of course, because the law only gives the information commissioner the power to recommend. Governments can ignore her recommendations with impunity.

Stephen McNeil, back when he was where Tim Houston was on August 22, 2021— premier to be — had promised to fix that. He never did because he found its toothlessness a convenient cover for his own government’s secrecy.

“I’m just wondering what they’re hiding,” Houston said at the time.

It’s a question we might ask now of Houston himself.

But not yet.

In 2019, the Tories took the government to court — their only expensive recourse to pry information from McNeil’s cold, dead hands. McNeil didn’t die, of course, but by the time of the court’s decision in February 2021, McNeil had resigned and been replaced by blink-and-you-missed-him Iain Rankin.

The court dispensed with the government’s main argument — that releasing the information would “harm the financial or economic interests of a public body or the government of Nova Scotia” — as a “mere possibility.”

As a result, thanks to Opposition Leader Houston, we learned that we — taxpayers — were/are funnelling $1.17 million a year into the coffers of Bay Ferries, whether their Yarmouth-Maine ferry ferries passengers or not. The ferry did not even sail in 2019, 2020 and 2021. Overall, the province still spends roughly $17 million a year keeping the non-service afloat.

After the decision, Houston told reporters he now knew why the government had fought so hard to keep the information secret. It wasn’t to protect the ferry operator’s proprietary information. “I think what we now know is the number is embarrassing.”

Fast forward to a still celebrating Premier-designate Houston five days after his party had won a free-to-do-whatever-he-decreed majority government:

“I know that there’s lots of Nova Scotians that have put in legitimate information requests that have got a lot of pushback, a lot of hurdles,” he [told CBC].

“We’re going to work with the privacy commissioner to make sure that the proper authority is there so that Nova Scotians have access to the information that they rightly should have access to.”

Uh… How’s that working out? For Houston? For the concept of transparent and accountable government? For us?

Here’s the premier again, but this time after one year in power:

Premier Tim Houston’s commitment to giving the province’s privacy commissioner more power could be softening.

Nova Scotia is the only province where the privacy commissioner is not an independent officer of the legislature. Recommendations from the commissioner’s office are not binding, which means government departments and other public bodies are not compelled to follow them.

“We’re looking at all the options, for sure,” Houston said to reporters at Province House on Thursday. “We’ll do the research and we’ll come up with the place that best suits the needs of making sure that Nova Scotians can access the information they’re looking for.”

It’s a departure from the commitment he made while in opposition to strengthen the commissioner’s authority. He also repeated the pledge about a year ago.

“We’re committed to it, there’s no question about that,” Houston told reporters last November.

After two and a half years in power — and after regular pleas from the information commissioner for that promised order-making power — the government has had more than enough time to demonstrate its commitment to doing what the premier himself knows is right.

It hasn’t.

Instead, the government announced in September that it would hide behind the skirts of an internal review. The review’s “working group” doesn’t include the privacy commissioner, but does include poohbahs from the Department of Justice and Service Nova Scotia. Those departments have, no doubt, been internal enablers of unaccountability and non-transparency for decades.

Under its terms of reference, says a press release, “the working group will also be accepting written submissions from the public and stakeholders outside of government.”

How important will those written submissions be?

Well, consider this. The Halifax-based Centre for Law and Democracy, which “works internationally to promote those human rights which it deems to be foundational for democracy, including access to information,” was one of the early submitters to the review.

Its 23-page submission offered a wide range of specific substantive recommendations for improving the Nova Scotia Act, including:

- The Act should be expanded to cover all bodies which are owned or controlled by government, which receive significant public funding and the judiciary.

- Consideration should be given to adding a section on proactive disclosure to the Act.

- The ability to extend the time limits for responding to requests beyond 60 days should be eliminated or substantially constrained and no fees should be charged for staff time spent responding to requests.

- The Act should set overriding standards for the secrecy provisions in other laws which it preserves, and the regime of exceptions should be substantially revised so as to protect only legitimate interests against harm, to make application of the public interest override mandatory and to impose sunset clauses on all exceptions that protect public interests.

- The independence of the Commissioner should be substantially improved, including by making it an office of the legislature, and the Commissioner should be given binding order-making power.

- Broader and more effective sanctions should be in place for officials who wilfully flout the provisions of the Act.

Worth at least discussing?

No.

When it delivered its submission to the government’s in-house committee, representatives of the Centre for Law and Democracy offered to meet with the committee to discuss its submission.

“The head of the committee refused to meet.”

That tells you more than all you need to know about this government’s commitment to freedom of information.

As does this comment from the premier’s press secretary to the Globe and Mail in response to a question about the committee.

No decision has been made about granting order powers and the decision will not be made until the review is complete.

And there’s no timetable for the committee’s “package of legislative options and recommendations [to be submitted] to the Minister of Justice to be tabled in the House of Assembly.”

Count on that date being after the next election.

Accountability? Don’t count on it.

***

A version of this column originally appeared in the Halifax Examiner.

To read the latest column, please subscribe.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books