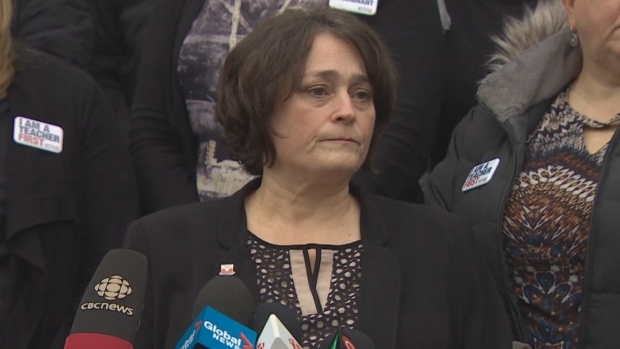

Liette Doucet. (CBC)

This column originally appeared in the Halifax Examiner February 26, 2018.

Cast your mind back to October 25, 2016. The date will be significant.

Before that day, Stephen McNeil’s Liberal government seemed to be in full control of its anti-public-sector-worker agenda. The executive of the Nova Scotia Government and General Employees Union was preparing — reluctantly — to recommend its 7,600 members agree to a tentative four-year deal with the province on the government’s take-it-or-take-it terms: say yes to a final and only “offer” of a three per cent wage increase over five years, with no increases in the first two years and no right to negotiate working conditions… or the government would impose draconian Bill 148, its collective un-bargaining legislation, to make things even worse and then impose its contract anyway.

The reason the usually militant NSGEU had decided to back down was simple. It felt alone. The only other major public sector union facing off against the Liberals, the Nova Scotia Teachers’ Union, boasted 9,000 members but most observers expected traditionally milquetoast teachers would ultimately go along to get along with the government.

True, union members had voted the previous December to reject a similar tentative agreement recommended by their executive, but that vote was just 61 per cent against, and the union executive’s immediate response had been to suggest it would ask for conciliation. There seemed little likelihood the teachers would take to the barricades.

But then, in June 2016, NSTU members elected a 26-year veteran of elementary school classrooms named Liette Doucet as its new president. Doucet, who’d been among the 61 per cent of teachers who’d voted against the agreement — “Personally I felt that the union should have realized that working conditions were a very real issue for teachers and that those things should have been discussed at the table,” she told the CBC, vowing that, as president, she would make teachers “proud that they supported me, and I will absolutely support them in whatever I can do.”

In early October, teachers voted again on a proposed contract. Doucet’s union executive again reluctantly recommended the deal as the best they could negotiate but telegraphed to members they would “respect” the wishes of teachers.

This time, 70 per cent voted no, and this time the union moved on to a strike vote.

On October 25, 2016, 96 per cent of more than 100 per cent of teachers voting (including substitute teachers) gave their union an overwhelming strike mandate.

And that changed everything about everything in the McNeil government’s union-busting calculus.

There was a teacher organized work to rule… a government-botched school-closure counter measure… a precipitous dip in Liberal support…

By mid-December, the NSGEU had changed its recommendation to its members from yes to no, and 94 per cent of them rejected the government’s offer too.

Though McNeil’s government — barely — won a second majority government last spring and, in August, proclaimed Bill 148, imposing its contract on 75,000 public sector workers, it is clear it has also created a new, newly energized and potentially far more powerful adversary, especially among the province’s teachers.

Last week, 82.5 per cent of NSTU members voted in favour of what could be an illegal job action in response to a government announcement it intended to move forward with sweeping changes to the province’s education system recommended in its own controversial, you-get-what-you-pay-for consultant’s report, which mirrored the government’s own desire to wipe out elected school boards, push principals and vice principals out of the union and create a new College of Educators to govern — and fire — teachers.

Teachers “made this decision knowing they could face a loss of pay and heavy fines,” Doucet told the CBC. “They’re so concerned for their students and the future of education in this province they’re willing to accept hardship in hopes that it will demonstrate to the government that the only way forward is through meaningful consultation.”

Doucet used the leverage of the overwhelming teachers vote to force a meeting Thursday with Education Minister Zack Churchill. Although it isn’t clear what will ultimately come out of that confidential meeting, or others that may follow — Churchill insists the government intends to press forward with implementing the consultant’s report during the legislature session that begins tomorrow (February 27) — it is clear teachers will no longer go along to get along.

And that’s good, for education, for labour relations and for us — if not for Stephen McNeil.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books