Lyle Howe (Jessica Durling, The Signal)

PART I: The Making of Lyle Howe

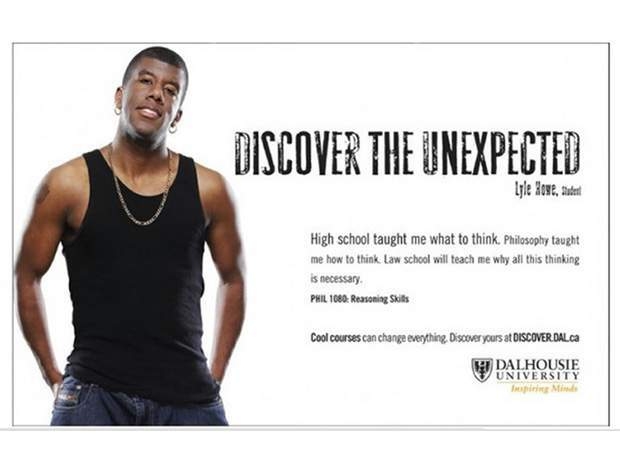

“High school taught me what to think.

Philosophy taught me how to think.

Law school will teach me why all this thinking is necessary.”

Lyle Howe

Dalhousie University

“Discover the Unexpected” marketing campaign

2006

“The Complaints Investigation Committee of the NOVA SCOTIA BARRISTERS’ SOCIETY

gives notice that the practising certificate of Lyle Howe of Halifax, Nova Scotia has been suspended pursuant to Section 37(1) of the Legal Profession Act, effective September 1, 2016 until further notice.”

Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society

September 1, 2016, 4 p.m.

On the afternoon of Thursday, September 1, 2016 — the eve of the Labour Day weekend — Lyle Howe was watching from the sidelines at Titans Fitness Academy gym in the Bayers Lake Business Park while his seven-year-son Tacari’s jujitsu teacher put him through his martial-art paces. Howe’s cellphone rang. It was a reporter. She’d just seen the posting on the Nova Scotia Barristers Society website about his suspension. Did he have any comment?

His what? This was the first he’d heard of it.

That’s not to suggest it was the first time the provincial lawyer-regulating organization had lifted Lyle Howe’s licence to practise law. Two years earlier, the bar society had suspended him without a hearing after he’d been convicted of sexual assault. Howe hadn’t protested. He’d been found guilty of a serious criminal offence, after all, and the society had a duty to protect his clients and the public. (Fifteen months later, after the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal overturned that conviction and ordered a new trial, the society reinstated him, but with conditions.)

Even though he’d been practicing law for just six years, Howe, in fact, seemed to have been in almost continuous troubles with the law, and/or with the legal profession. He’d twice been charged with serious criminal offences and was, at that very moment, in the middle of what would become the longest, most expensive professional misconduct hearing in bar society history.

But, despite even those professional misconduct charges, the society had continued to allow Howe to practise, with various conditions, while his hearings continued.

Until today…

If the society was now suspending him again — without asking for his response, or even notifying him— this must be serious, Howe thought.

He racked his brain. Stealing from a trust account? Fabricating a legal document? Those were the kinds of protect-the-public offences for which the society might justifiably unilaterally suspend a lawyer. Howe knew he hadn’t done anything of the sort. Criminal charges? Howe was confident he hadn’t done anything criminal, but of course he’d been charged with crimes in the past in situations he believed either were not criminal or simply hadn’t happened. Were the police on their way to arrest him at this very moment?

He panic-called Marjorie Hickey, the lawyer who represented the provincial bar society. Should I get someone to come pick up my son, he asked?

No, no, she said, it’s not that kind of complaint. But she wouldn’t tell him what kind of complaint it was. In fact, to this day, the society has neither formally charged Howe in connection with those particular allegations nor lifted his suspension. Darrel Pink, the society’s executive director, tells me “the matters that resulted in the current suspension remain under investigation.”

So, while Howe prepares to make his final arguments next month in response to the society’s initial professional misconduct charges against him — charges that could lead to his disbarment — he remains in a kind of legal limbo-hell, his professional and personal reputation in tatters, unable to earn a living as a lawyer.

What’s going on here?

Lyle Howe believes he knows. It is, he says, because he’s black. He freely admits it’s probably more complicated than just that. But he insists it is almost certainly that too.

***

The Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society disputes that claim. In a written response to questions I posed about the case, Pink said: “The Society maintains that there is not a shred of evidence to support any allegation that racism has played any role in the current charges against Mr. Howe.”

That said, in a province with 20,000 African Nova Scotians whose history traces back to the early 1600s, the issue of race inevitably simmers close to the surface whenever we talk about justice in Nova Scotia. Consider a sampler from the last year alone:

- Last February media students at the Nova Scotia Community College published “Untitled: The Legacy of Land in North Preston,” an investigative report that demonstrated “the stunning fact” many people who live in historically black communities still do not have legal title to their land 200 years after the first settlers arrived.

- In March, another research group published a report showing the “disproportionate impact on African Nova Scotian and Aboriginal communities” of government decisions on where to locate waste disposal, landfill and industrial sites.

- In April, Sobeys, a Nova Scotia-based company that is not only the province’s largest supermarket chain but also one of its most important historic employers, challenged the findings of an independent human rights commission that it had racially profiled one of its customers, only finally backing down and apologizing after intense public pressure.

- In May, VICE Magazine published a report about a series of recent murders in Halifax involving young black men. The headline: “How A String of Murders in One Canadian City Reveal Its Racist History.”

- In September, the Globe and Mail, reporting on Canada’s racial divide, quoted Halifax pastor Dr. Rhonda Britton not only recalling the 2011 spray-painting of a plaque in front of her north-end Halifax church with the words, “Fuck All Niggers,” but also her feeling that racial tensions in the city were “coming to the boiling point.”

- In January of this year, a CBC news investigation revealed that blacks in Halifax are three times as likely as whites to be the subject of police spot checks.

And let’s not forget either that, less than 30 years ago, a seminal royal commission looking into why a young native man named Donald Marshall. Jr., spent 11 years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit concluded that Nova Scotia had a deeply entrenched two-tiered justice system: one for the privileged, and another for blacks and natives.

Darrell Pink knows that history well. In response to the 1989 Marshall Commission report, the bar society established what became the only permanent standing racial equity committee in any bar society in the country and has since developed what Pink calls “a well-established and internationally recognized commitment to equity, cultural competence and addressing issues of systemic racism and discrimination in the legal profession.” He has his own collection of proactive bullet points, including:

- In early 2015, the society launched #TalkJustice, an initiative to bring public voices into justice system reform, with a focus on the voices of “equity-seeking partners in particular.”

- The society’s equity and access office, which recently won a national Zenith award for “advancing diversity and inclusion in Nova Scotia,” is acting as an advisor to that Preston Land Title Clarification Pilot Program, which is designed to finally clear up title to those untitled lands.

- The society opened an “equity portal in December 2015 full of “toolkits, model policies, assessments, articles, cultural competence training videos, a reference library and much more” to help lawyers in “developing cultural competence and building equity strategies in their practices.”

“We recognize,” Pinks adds, “that, no matter how far we have come, there remains more work to be done.”

So how does the case of — the story of — Lyle Howe fit into these larger narratives?

***

“You’re being allowed back into school, but you shouldn’t expect to graduate in June,” the principal explained, not unkindly, to 15-year-old Lyle Howe. “Think of these next few months as your chance to start over, to get ready to do Grade 9 right next year.”

Five months earlier, in November 1998, Lyle had been expelled from Highland Park Junior High School for fighting. “I wasn’t a bully or anything,” he insists today. He describes himself instead as “mischievous,” adding, “it was a rough school.”

Despite his mother Trina’s best efforts, no other schools would accept him. Finally, Trina asked Barbara Hamilton-Hinch, a community leader and friend, to smooth the waters at their neighbourhood school, St. Pat’s-Alexandra. Hamilton-Hinch agreed, but warned young Lyle he had better be “very good. I put my neck out for you.”

So now Lyle was back in school, but the principal was already telling him he wouldn’t graduate in June.

“Why not?” he asked.

“Because you’ve missed too much time.”

“But what if I do really well on each exam?” Lyle persisted. The principal smiled indulgently. Even his mother suggested Lyle not expect too much.

But Lyle would not be deterred. “I read every text book from beginning to end,” he recalls today. In the end, despite having been away from the classroom for nearly six months, he aced his final exams and graduated as scheduled.

The lesson? “That showed me I was capable of doing anything,” Howe says today. “It gave me confidence. Where I came from,” he adds, “it wasn’t an easy place to have confidence.”

Where Lyle Howe comes from turns out to be… well, complicated.

***

When Trina Briand became pregnant with Lyle in early 1984, she was just 16; Lyle’s father, Robert Howe, was 19. Robert was a son of one of Africville’s historic black families. Lyle gets his dark skin and facial features from his dad’s side of the family. His mother, Trina, is a lighter-skinned black woman whose mother, Carol, is white but had married a black man who fathered Trina. By the time Lyle came along, Carol had split with Trina’s biological father and married the white man Lyle would come to know as his grandfather.

When Trina told her mother she was pregnant, Carol volunteered to look after the baby so Trina could continue in school. For the first five years of his life, Lyle lived primarily with his white grandmother and grandfather — “she was my lunch monitor at day care” — three white uncles and two white cousins. “Me and my mom,” he jokes, “were the only blacks in the family.”

It was the beginning of what would become — and still is — a complicated racial duality. “I became closer to whoever I was with at the time,” Howe tells me. “When I was with whites, I would talk white, act white. My grandmother always made sure I spoke well.” Before she died, Lyle remembers her telling him: “I gave you the skills you’ll need to survive in a white world.” But, he adds, “when I was in Africville, with my dad’s side, it was a totally different experience. They spoke differently. They had a lot of anger, a lot of frustration with white people.”

When he was six, Lyle’s parents tried living together, but it didn’t last. At one point, Lyle remembers, the police busted down their door and swarmed in, guns drawn, searching for Robert and for drugs. They found neither, but smashed up the apartment anyway. A traumatized Lyle ended up in counseling, and developed a sleep disorder that persists to this day.

Lyle’s father was in and out of his life, showing up on birthdays and special occasions, but leaving the more difficult day-to-day parenting to his mother. “I remember when I was in Grade 5 or 6,” Howe says, “[my father] just showed up one day outside my classroom asking to see me.” He’d decided Lyle needed new and better clothes than the ones his mother provided, so he told Lyle to meet him after school and they went on a shopping spree. “He bought me all sorts of winter clothes, a bunch of tuques… I still have some of them today.” Needless to say, Lyle’s mother was not amused, and there would be continuing friction between his parents.

Mother and son eventually settled in Hamilton Lane on the edge of Uniacke Square, the north-end public housing project. “In all of Uniacke Square, there’s only been one other lawyer that I know of, and he’s a crown prosecutor,” Howe tells me pointedly. “Where I come from, you’re more likely to be shot and killed, or go to jail for life than you are to become a lawyer.”

Howe points to his Grade 9 class picture. There were just nine students, “two white guys, a girl who was pregnant and the rest of us, all young black men. A few of the black guys I went to school with did go on to high school, but not one of them graduated.”

He mentions his own son, Tacari, now a Grade 2 student at the private Halifax Grammar School in south-end Halifax. “It’s a great school,” Howe says. “He gets individual help when he needs it. He’s reading really well. His mind is in the right place…” He pauses, allows the unspoken thought to stay unspoken for a moment. “What we have is a systemic problem,” he says. “We are not expected to succeed, and that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

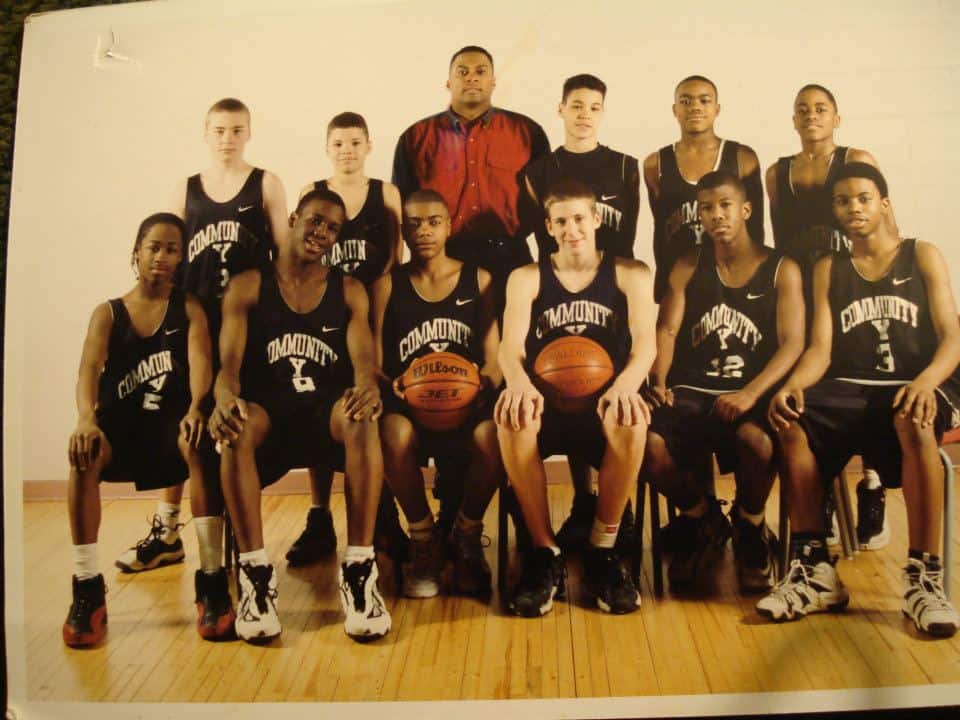

Lyle Howe, front row second from right, as a member of the Community Y Basketball team. Tyler Richards is to the right of the coach in the photo. Next to him is Maury Howe.

His own academic path certainly had its zigs and zags. After scoring in the 90s on his Grade 9 final exams, Lyle’s Grade 10 year at St. Patrick’s High School was an academic disaster. He did well enough on tests, but didn’t bother with class projects, or showing up for classes. He even spent two months that winter in Florida. The results were predictable: he barely scraped through with marks in the 50s and 60s.

Which is when his mother came up with an incentive she hoped would push her very competitive son back on the right track academically. She promised him $50 for every “A” he scored on his exams.

“But mom,” he said, “you know I’m taking eight courses?”

She did. “It was worth it,” Trina tells me today.

It was. “I went crazy,” Howe remembers, “first so I could earn the money, which was a lot in those days, and then I discovered I loved it. I got addicted to getting good marks. They used to list your rank in the school after every semester. I wanted to rank higher every time.”

That led to another, perhaps less predictable — and more personally complicating — development. “I began to hang out with the nerds,” he says. The nerds were mostly white. He stopped hanging around with his childhood friends, who were almost all black. “There was a lot of backlash,” he remembers. “I was called white, Uncle Tom. My old friends would pick at me. It was hard.”

His separation from his neighbourhood friends had actually begun in Grade 10. Lyle and most of his friends tried out for the St. Pat’s high school basketball team. Lyle was the one cut. At the time, basketball was a critical aspect of his identity, and he was devastated. He’d grown up playing hoops at the Community Y and Highland Park Junior High with the likes of Tyler Richards, a boy a year younger than him, who would go on to star at St. F.X. and later played for the Halifax Rainmen of the National Basketball League of Canada.

“I was never that good,” Howe admits, but he now believes being cut by the team — as crushing as it was to his ego at the time — turned out to have been “one of the best things that ever happened to me. I got a different mindset.” He stops, adds: “Look at the last seven murders in Halifax. How many of them played basketball?”

Tyler Richards certainly did. In April 2016, the 29-year-old, whose promising career careened off the rails after he got tangled in the local drug underworld, was shot and killed in a still-unsolved murder police say was “not a random act.” Before he died, Lyle represented Tyler on a drug charge.

Howe shows me a photo on his phone. It’s a team photo of the Community Y Panthers from the late 1990s. “There’s me,” he says, pointing, “and there’s Tyler behind me. Beside Tyler, that’s Maury.” Maury Carvery, two years younger than Howe, was murdered in 2006 in yet another unsolved homicide, also thought to be drug-related.

For his part, newly nerdy Academic Lyle — boyishly charming, fun to be around — became a popular member of St. Pat’s white “student council crew.” In Grade 12, the entire student body elected Lyle student council president.

By then, he says, he’d already decided on his career path: he would become a lawyer.

***

It was late November 2006, and Howe was waiting for his first-year property law course to begin. Law school had not turned out to be what he’d expected — for all sorts of reasons.

For starters, it was more academically challenging than he’d expected. He had breezed through undergrad, which seemed like an extension of high school. He’d earned a psychology degree with good marks, and made a positive enough impression on campus to be featured — striking a cocky pose — in a university marketing campaign.

In law school, Howe tried to do what he had always done to succeed. He read every word of every page of his legal text books. But he kept losing the forest for the trees. It wouldn’t be until his second year when one of his white professors, David Blaikie, “spelled it out for me.” He showed him how to find the legal big picture trees in the forest of words, directed him in the use of condensed annotated case notes. “He was great to me,” Howe recalls.

But it wasn’t just the academic rigour of the law school that shocked Howe. There was also the culture shock. There were two African Canadian professors and only a few black students in the entire law school. He felt “surrounded by privileged people” — faculty as well as students — many of whom, he believed, looked down on a poor black student from Halifax’s north end.

Although Howe had entered law school through the traditional academic/LSAT route, he had gotten some funding from the school’s Indigenous Blacks & Mi’kmaq Initiative, a program designed to increase representation of minorities in the legal profession.

“It must be nice to get funding,” he remembers one white student telling him. “No one’s funding me.”

By the time he smacked up against that other fellow student casually employing the n-word, Howe already felt like an outsider. The incident that sparked the classroom discussion that day had begun a few nights before when Michael Richards, a former star of the hit series Seinfeld, had been caught on camera verbally attacking a heckler at his standup comedy show by repeatedly calling him a “nigger” and ordering security to “throw his ass out.” After the video went viral on the Internet, of course, it became the subject of conversation everywhere, including in campus classrooms.

Although Howe wasn’t a participant in the conversation before class that day, he couldn’t help but overhear his fellow student’s comment. He was offended. He said so. He asked the student if he condoned Richards’ remarks.

“Condone is a big word,” the student responded with what Howe took to be condescension.

Other students jumped in to support the white student. He can say what he wants. You can’t tell him what to say. As the conversation escalated, another student — a white woman Howe had considered a friend — told him he was becoming “too aggressive,” and suggested he go out into the hallway to calm down.

Howe did go into the hallway, but he couldn’t calm down. Later, he and David Currie, one of the few other black students in the law school, took their concerns to Michelle Williams, the head of the IB&M program, the law school’s dean and the professor himself. Philip Girard, the property law prof, himself raised the issue at the start of the next class, making it plain such comments were unacceptable. The student who’d made the remarks stood up to acknowledge what he’d said. “He may even have apologized,” Howe says now. Although he allows that Girard was trying to do “the right thing,” the incident only served to further isolate him from his fellow students. “I was ostracized, the black sheep in the class. It made me feel even more uncomfortable.”

Although Howe would go on to be elected president of the Black Law Students’ Association and win the 2007 Judge Corrine Sparks Award — presented annually to the law student “committed to using their legal education as a tool for change in their community” — he remembers law school as a difficult, painful experience.

It wouldn’t get any better after he graduated.

Part II: The Unmaking of Lyle Howe (Available March 9, 2017.)

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

I taught Lyle in high school econimics. He turned out to be one of the best students I ever taught, and was a strong positive influence in the classsroom. If anybody ever deserves another chance it be Lyle Howe.

Alex Roberts

i dont want my child growing up in a world with people like Lyle HOWE in it…..he is a disgusting pig, his poor children.

I don’t want my kids growing up in a world with judgemental people like you.