It’s been a year since the Government of Nova Scotia’s surreal slashing of its film tax credit. Why did they do it? What did they hope to accomplish? How has it impacted production? Stephen Kimber investigates.

“Mr. Speaker, the tax credit is important, and it is a powerful tool to our economy… The film industry in our province is worth millions of dollars and the producers of these films are putting hundreds of thousands, and sometime millions, of dollars on the table to do productions in our province…”

Diana Whalen

Opposition Liberal Finance Critic

April 30, 2013

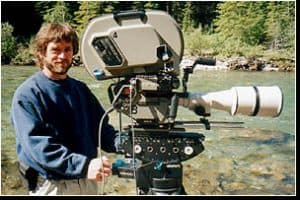

It was shortly after 4 p.m. on Thursday, April 9, 2015. Christopher Ball had just left an interview for a next job as a camera operator on an upcoming American film project on the way to a pre-production meeting for a small independent feature he was scheduled to begin shooting as director of photography the following week.

Two thousand and fourteen had been a very good year, the best since Ball and his wife, Kristie Sills, a second assistant director for film and TV, moved to Nova Scotia in 1997. Though born in Ontario, they’d begun trekking to the Maritimes in the early nineties to work on various movie projects and discovered they wanted to make their futures here. They bought a lakefront property near Mahone Bay on Nova Scotia’s south shore and moved in. Their two sons were born in Nova Scotia, and the family became enmeshed in the local community, joining everything from a canoe group to a book club. Ball taught a course at the Nova Scotia Film Co-op, and helped run a Lunenburg County film series. Along the way, he transformed his own passion for aviation into a side business, operating an ultralight flight school.

And, of course, he helped build what had become a significant film and television industry in the province. While Kristie often headed back to Ontario for work — a Toronto producer she’d worked with there invited her back frequently to be part of his production team — Ball himself found more than enough to do in Nova Scotia. “Things would start up in the spring each year,” he explains. “By Christmas, it would be insane.”

Last year had been the most insane. He’d trampoline-bounced from a CBC kids’ series called You and Me to an exhausting double season of Haven, a U.S. sci-fi series, with barely a week’s break between. While Haven had ended its five-season run, the show’s Nova Scotia producers had already asked Ball about his availability for “another big series” they were negotiating to shoot in 2015. Mr. D., the CBC comedy series, wanted him back to work on its new season. And there was the already scheduled work on the independent feature, and…

Nova Scotia Finance Minister Diana Whalen — she of the “tax-credit-is-a-powerful-tool” talk while an opposition MLA two years before — had just introduced her government’s 2015-16 budget, and the 20-year-old tax credit ended up dead centre, not to mention dead-on-arrival, in her cost-cutting crosshairs.

The credit had provided a rebate of up to 50 per cent of a production’s Nova Scotia labour costs, up to 65 per cent if the producers were frequent filmers, or shot their projects outside Halifax. Last year, the open-ended program — which Whalen now described as “one of the most generous in the country” — had cost the provincial treasury $24 million.

Her government was staring at a $98-million deficit and desperately seeking ways to cut it, especially as it began gearing up for re-election. The tax credit seemed a good place to start.

Whalen’s “revised” credit capped funding at $10 million, meaning producers would now have to scramble to access limited dollars. Since the credit would no longer be a sure thing, even producers who qualified for funding couldn’t use the expectation of tax credit revenue — which is not paid out until after a production is wrapped and audited — to leverage interim funding to pay production costs. Which meant other investors wouldn’t likely be interested in investing, which meant…

Worse, the new credit, though on more than just labour cost, would only be 25 per cent refundable. The remaining 75 per cent, Whalen told the legislature, would only be “available to film companies against the taxes they pay.” But the reality is that production companies are almost always purpose-built, pass-through entities that spend all the money they raise in order to create their projects. Such companies don’t themselves pay taxes (though their parent companies do), so they wouldn’t qualify for any tax credit. Oops.

It quickly became obvious Whalen’s finance department hadn’t consulted the industry before concocting its scheme. Halifax Chronicle-Herald legislature reporter Michael Gorman, who later described finance department officials as “woefully unprepared to answer what should have been obvious and anticipated questions,” tweeted after the pre-budget lockup: “Dept officials admit [new program] is less competitive and are uncertain of full impact.”

“I had a gut feeling,” Christopher Ball remembers. “This doesn’t sound good at all.”

It wasn’t. By the end of the day, shooting for his next week’s independent feature had been been put on hold, and every major film and television project planned for the rest of the year was suddenly in jeopardy.

***

Sheila Lane was in her downtown Halifax studio that same afternoon with award-winning Spanish screenwriter and director Paco Arango. They were matching actors with roles for his latest feature film, The Healer, a romantic comedy scheduled to shoot in Lunenburg that summer.

Lane’s Filmworks had been casting Maritime-based film and TV projects for 20 years. In 2014, she’d helped select stars, bit players and in-betweens for Haven, Mr. D., Trailer Park Boys and the Tom Sellick series Jesse Stone, not to mention a number of smaller independent films. Given the sinking value of the Canadian dollar, Lane believed more international productions like The Healer would require her services before the coming season ended.

Arango had flown to Nova Scotia the year before after hearing about its film tax credit — and discovered Lunenburg. “It was love at first sight,” the film’s producer later told a reporter for a local newspaper. “Paco fell in love with Lunenburg’s architecture and beauty.” He liked it so much, in fact, he decided to make Lunenburg not just the film’s primary location but also one of its visual “stars.” The province’s film tax credit helped finance the project.

But now, as he listened to the parade of fearful, auditioning actors outline changes that would eviscerate the tax credit, Arango exploded. “What the fuck!” he shouted, jumping up and down, waving his hands in the air. “Do they think I come here for the weather?”

***

“No way,” MacDonald, a longtime camera operator and the owner of Take One Atlantic, the region’s largest supplier of specialized film support vehicles, reassured his co-worker. “That would be the stupidest thing they could do.”

MacDonald’s own career had evolved, along with the province’s film industry, over the past 25 years. Back in 1988, while working as a camera assistant on Little Kidnappers, his first feature film, MacDonald built himself a camera truck so he’d have a place to work during production. The producers were so impressed they asked if he could build a hair-and-make-up trailer too. He did. That was the beginning. “Every time I’d get a job, I’d go to the bank and get another vehicle. I built the business one truck at a time.” Take One Atlantic now boasted a fleet of 30 purpose-built vehicles, most of which were constantly hired by production companies shooting in the Maritimes.

When he was campaigning to be premier in 2013, Liberal leader Stephen McNeil had reassured the film industry his government would be “extending the film tax credit… for an additional five-year period.” MacDonald had taken that reassurance to his bankers, convincing them to lend him the money to acquire three more vehicles.

“Don’t worry,” MacDonald told his assistant. “It’ll be fine.”

It wasn’t — and it isn’t.

***

“Recent studies link the arts, culture and the creative sectors to positive impacts in employment, community development and social inclusion and well-being…”

Now or Never: An Urgent Call to Action for Nova Scotians

Ivany Report on Nova Scotia’s economic future, 2014

Government incentive programs to lure filmmakers to produce programs in a particular state or province have become ubiquitous. The incentives emerged in the late twentieth century as the costs of making Hollywood movies in actual Hollywood skyrocketed, and producers sought cheaper alternatives. Governments of all sizes and shades were more than happy to oblige. Today, close to 40 states and every province in Canada, except Prince Edward Island, offer filmmakers some form of pot sweetener.

Why? Well, for starters filmmaking is not only more glamorous than your average runaway call centre but it is also a cash churner. Production companies are created to spend their budget, most of it where they film.

Producers descend on a location, often rural, and inject a lot of money into its economy in a very short time. They rent offices, buy supplies, employ dozens, sometimes hundreds of skilled local crew and workers, paying them top dollar. They book flights, fill up hotel rooms, rent vehicles, eat in restaurants, drink in bars. They hire caterers to care and feed the crew on set, and those caterers shop for everything from asparagus to zucchini through local suppliers. The art department drops its budget buckets at area hardware stores on plywood and paint to create sets, then shops locally for furniture, antiques and knickknacks to decorate them. The wardrobe department shovels thousands of dollars into the coffers of local clothing retailers, buying everything from underwear to top coats to dress the actors. And then there are the actors. While stars may come from away, there are almost always smaller roles for local actors and extras.

Nova Scotia introduced its film incentive tax credit in 1995 at a time when the province’s film and television production sector accounted for just $6 million in economic activity. In 2014, according to a 2016 PwC study commissioned by Screen Nova Scotia, an industry group, film and TV production generated $180 million worth of provincial GDP and created work for more than 3,200 people (1,600 full-time-equivalent positions, and 1,600 indirect jobs).

“When you compare the $24 million (the province paid out in tax credits) to the $180 million in GDP,” notes Marc Almon, the chair of Screen Nova Scotia, “that’s a ratio of seven to one.” Almost none of that economic activity would have happened if not for the lure of the tax credits.

Bernie Smith, a former provincial deputy minister of finance who wrote a favourable report on the economic benefits of the film industry for the provincial government in 2000, has extrapolated from those numbers that film activity in 2014 generated $18 million in worker payroll taxes plus another $4 million in sales taxes , creating almost a wash of the $24 million credit — even before the value of the economic activity, and the many spinoffs, is taken into account.

How do all those global numbers translate into the daily economic real life of creating cinematic fantasy in Nova Scotia? Consider Haven, the science-fiction-series spawn of a Stephen King short story. During its five-season run on Nova Scotia’s south shore, the show’s producers claim it spread millions of dollars among nearly 1,300 vendors. Cast and crew ate 180,000 meals, “most of which came from local farms, butchers, fishermen and markets.” In addition to the 6,200 local actors and extras who appeared on the show, Haven rented 2,000 vehicles just to background its scenes. That’s in addition to the 442 production cars and 633 other vehicles it needed to make that TV magic. Collectively, those vehicles guzzled 782,000 litres of fuel, all pumped locally.

According to the producers, “conservative estimates value this compound spending generated by Haven’s production cash flow at close to $140 million.” Certainly not chump change in an economically depressed rural region.

But the benefits go beyond spent dollars and cents, tax credit supporters argue. Over the years, thanks in part to the invaluable experience Nova Scotians gained working on international “service” productions like Haven, the province has also been able to construct its own thriving local industry, enabling Nova Scotians to tell their own stories on big and little screens. Between 2010 and 2014, the percentage of local productions that qualified for the tax credit increased from 56 per cent to 88.

The need for ever more skilled crew to support more and more productions also led to the development of a two-year Screen Arts diploma program at the Nova Scotia Community College and a Bachelor of Fine Arts with a specialty in Media Arts degree at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.

As for film industry workers themselves? The PwC report describes them as better educated than your average Nova Scotian, younger, likely to have arrived from away and — thanks in part to the freelance nature of their business — equipped with “relatively high entrepreneurial inclinations… an essential ingredient for the development of a creative economy.”

Tellingly, those are exactly the kind of workers the 2014 Ivany Report — a searing examination of what Nova Scotians need to do to overcome the overwhelming challenges of a declining and aging population, which politicians and pundits reverentially reference daily —argued the province should be trying to attract more of. Instead…

And that’s still not all. At its peak, it’s worth noting that Haven attracted an average 2.4 million viewers per episode. Although ostensibly set in the fictional town of Haven, Maine, the show more than showcased the real-life beauty of Nova Scotia. And then, of course, there’s Paco Arango’s The Healer, set for theatrical release this year, which will showcase Lunenburg’s many charms. How do you quantify the value of that free promotion compared to, say, the millions the province spends annually on tourism advertising?

***

“If we are going to improve our prospects for the future, we all have to feel some pain.”

Diana Whalen

Nova Scotia Minister of Finance

Pre-budget speech

Halifax Chamber of Commerce

March 25, 2015

So what’s the downside?

Well, for starters, not everyone buys the rosy numbers — especially the multiplier effects its supporters tout. Nova Scotia’s finance department pegs the economic value of Nova Scotia productions at just over one-third of the $180 million the PwC report claims (although that’s still three times what the province shelled out on the tax credit).

Premier Stephen McNeil argues the tax credit is not really even a tax credit. “It is a direct labour subsidy that is unsustainable for a province that has to deal with all of the other challenges,” he told the CBC. “Imagine if we subsidized labour of every Nova Scotia company to 65 cents (per dollar) of the labour costs.”

The jobs the industry creates, critics also point out, aren’t permanent. If productions don’t continuously beget more productions, you end up with a trained workforce without work. And the competition for those productions is fierce. Which jurisdiction is offering the most lucrative incentive this year?

“It is unclear how these sorts of competitions end,” the California legislative analyst’s office reported two years ago as that state pondered upping its own incentives to lure filmmakers back. “In responding to other states increasing subsidy rates, California may only stoke this race to the bottom.” Despite that concern, California tripled its available incentives.

The other issue with incentive programs like Nova Scotia’s is that there’s no cap on how much they can ultimately cost. This spring, the British Columbia government cut its own incentive by five per cent simply because its industry had become too successful. While producers there spent $2 billion and employed 22,000 people in 2014-15, the uncapped tax credit threatened to vacuum up $500 million worth of scarce tax dollars.

That said, B.C. government officials made their tinkering changes in careful consultation with the industry — something that didn’t happen in Nova Scotia.

Industry spokespeople here acknowledge the Nova Scotia tax credit may indeed have become too generous — especially in light of the falling Canadian dollar — but they say the government’s unilateral, ham-handed handling of the changes has now , perhaps permanently, killed the goose that laid so many golden eggs.

Over the course of 20 years, governments of all stripes successfully deployed the tax credit to help nurture what became a thriving industry with a highly-skilled, well-respected workforce and dependable, cover-the-waterfront local filmmaking infrastructure. If the McNeil government had simply nipped and tucked at its edges to make the tax credit less generous, it could probably have saved itself some money and protected the industry’s future at the same time. Instead, it created a new system that not only doesn’t work for the industry but is so convoluted and difficult to navigate the government hasn’t even been able to give away two-thirds of the $10 million it set aside for the new Nova Scotia Film and Television Production Incentive Fund. Which means a province desperately in need of new jobs is eliminating existing ones.

McNeil wasn’t moved. Even after PwC — an international accounting and consulting firm the province itself often turns to for economic advice — made the business case for the tax credit, McNeil dismissed it out of hand. “I think (our new system) is fair, it’s there, and I’m looking forward to people using it.”

In fact, the month before the PwC report, the Atlantic Council of the Directors’ Guild of Canada reported the bottom had already fallen out of the industry, with both its members’ salaries and days worked cut in half since the government announced the changes. Worse, much of the work they did report was completed under the old tax credit system.

The DGC also pointed out that other jurisdictions that had cut their film incentive programs — including Saskatchewan and New Brunswick, which both cancelled, then reinstated programs — lost much of their industry as a result.

So why did the McNeil government do what it did?

No one knows for sure, but it seems likely someone somewhere in the bowels of the finance department — under intense pressure from above to find actual spending to cut, partly because government revenues were tight and getting tighter, and partly because the government wanted to be able to massage its way to a balanced budget before the next election — circled the $24-million expense line item as a prime cutting candidate without working through, or perhaps even understanding, the implications.

There have been implications.

***

When I caught up with Sheila Lane via Skype, she was in Chelem, a small town in Yucatán, Mexico, “avoiding winter and teaching English as a volunteer.

“At first,” she explains, “I kept a positive view. I couldn’t believe they wouldn’t see the error of their ways. You have to remain hopeful. Otherwise you just break down.”

Last December, she finally shuttered Filmworks — she’d had no work on the books since August — and headed south. Although she plans to return to Halifax for a couple of projects this summer, “I can’t make it on two productions a year.” She’s considering setting herself up as a casting agent for American productions shooting in Mexico. “There’s lots of action down here… But—” She leaves the thought unspoken.

With two teenaged boys busy with school and friends and sports activities, Forbes MacDonald says he isn’t moving anywhere for now. But he’s already had to adjust.

Last week, MacDonald was in Toronto trying to line up business there for his fleet of trucks. “I sent seven pieces of equipment to Ontario,” he says, “but it’s costly. You have to pay for drivers, hotels, gas…” This morning, he got a call from producers in Sudbury, where the film business is booming. “They want another truck.” He also got a text from a friend — a Nova Scotian film technician who had moved to Sudbury for work. “Saw your logo on a truck here this morning,” he wrote. “Made me homesick.”

Next week he flies to Ontario for a short stint as a camera operator, his first production work since The Healer last June. (Arango moved up production in order to shoot his film under the old tax credit.)

Last December after his wife finished work in Ontario, Christopher Ball and Kristie Sills sat down and took stock of their situation. If they both had to spend most of their year working in Ontario, did it really make sense for them to continue to live in Nova Scotia? They ultimately decided they had no choice but to move back to Ontario once their boys, seven and 10, finish school this year.

They’re not alone. “I know of at least 20 other people who’ve left already. Businesses too,” Bell says. “We loved it here and we’ve become so immersed in life here, but… what else can you do?”

— Originally published in Atlantic Business Magazine, July-August 2016

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

This is a great article! I’ve always liked Steven Kimber, ever since he was in the living room speaking with my mother about the crazy idea of putting a four lane connector road through the North End of Halifax in the 1970s. How backwards Nova Scotia can be!