Havana, September 4, 1997, 11:00 a.m.

Fabio Di Celmo was apologetic. Another day perhaps, he suggested into the telephone. The person at the other end of the line was a representative of Biconsa, a division of Cuba’s Ministry of Domestic Trade with whom he hoped to make a deal. But not today. Their appointment was for noon, but Fabio had a more pressing commitment at that time. Enrico and Francesca Gallo Argelia, his two best “buddies” from his school days in Italy, had been honeymooning in Cuba and were flying home this afternoon. Fabio, who’d suggested the newlyweds’ honeymoon destination, had promised to have one final lunch with them before they left.

Perhaps, Fabio suggested into the phone, he could meet with the Biconsa representative next week. He really did want to do some business. Of course. Yes, yes, that would be fine.

Fabio hung up the telephone, explained the new arrangements to his father. Giustino nodded. While Fabio met with his friends in the lobby bar at the Copacabana, Giustino would return to his room on the fourth floor to rest for a while. Perhaps later, he said, he’d join them for a drink.

Fabio was feeling good. About himself, about business, about life. At 32, he senses that he was finally emerging from his father’s business shadow. Although he was now 77 years old, Gisutino Di Celmo still cast a long shadow.

Giustino had been—still was—a natural-born salesman, a larger-than-life figure who could peddle anything to anyone. But that did not, his oldest son Livio would be quick to insist, make him a capitalist. “My father’s motto was to treat everyone fairly. Capitalism was OK if the profits benefitted everyone equally,” he would explain. “Otherwise, capitalism was the big enemy.”

After World War II, Giustino had left war-ravaged Italy for the promise of a better life in the new world. His wife Ora joined him later. They’d settled in Argentina where Giustino could weave his selling magic—at one point he bought a boat to travel up the Rio Parana to buy fish from the native Indians to sell in Buenos Aires—while Ora would raise their two young children, Livio and Titania. (Giustino, who was a Roman history buff, named all his children after famous Romans.)

But Giustino’s friendships with anti-government union leaders soon brought him into conflict with Argentinian strongman Juan Perón. After some of his friends wound up murdered, Giustino packed up the family and returned to Italy.

Fabio—in Roman times, a name given to a “special person”—was born in 1965.

From his new base in Genoa, Giustino developed a thriving export business, selling much-needed furniture for hotels as well as fine Italian jewelry to outposts of the Soviet empire like Czechoslovakia. In the early 1970s, he also began travelling to Canada peddling stylish Italian jewelry in Montreal. By 1976—the year of the Montreal Olympics—the family officially became permanent Canadian residents, allowing them to spend part of the year in Montreal and part in Italy.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s threatened Giustino’s own small empire, but he quickly parlayed an old friendship with the Czech trade minister into an introduction to Cuba’s minister of domestic trade.

The loss of its Soviet benefactor had plunged Cuba into sudden economic freefall and forced Fidel Castro to turn, reluctantly, to tourism to generate desperately needed revenues. Attracting visitors to the island meant building world-class tourist resorts. And that, of course, meant a sudden need for beds, furnishings, carpets, cleaning supplies, everything.

Giustino Di Celmo was more than ready to supply those needs.

In 1992, Giustino and his youngest son Fabio flew to Havana to meet with Cuban Domestic Trade Minister Colonel Manuel Vila Sosa. Fabio was impressed, he would tell his older brother afterward, and not just by the fact the first thing Vila Sosa did was to pick up his cellphone and call Czechoslovakia to make sure the Di Celmos really were friends of the minister, but also by the fact that the minister, a colonel in the Cuban army, dressed for work in jeans and a T-shirt. Fabio was going to like doing business in Havana.

Fabio, who hadn’t been especially interested in pursuing academic studies, had joined his father in business after high school. He liked the independence that came with selling. At first, he’d just been his father’s assistant, listening and watching while Giustino spun his salesman’s web. Over time—although his father continued to handle the business’s financing and accounting—Fabio had assumed more and more responsibility for finding the products they sold and for maintaining quality control over them.

Thanks to competitive prices, on-time deliveries and quality products, sales had been brisk. One of their first big jobs was a contract to supply Italian furniture and carpets for renovations to the venerable Hotel Nacional. There always seemed to be more opportunities. Cuba, as Fabio liked to say, needed “everything.”

Recently, Fabio had finalized the first two contracts he’d negotiated completely on his own. One was for sewing machine needles. For some reason, no one in Cuba had been able to find a supplier for the machines. Fabio had. The deal had been a personal breakthrough, Fabio explained to his older brother in a phone conversation two days before, because he’d accomplished it all by himself. Fabio encouraged Livio—who was then living in Montreal and had just lost his own job with an airline there—to abandon his life as “an office rat” and come work with him in Cuba. “We’ll have fun together,” he’d said.

Though Fabio still flitted frequently among Cuba, Canada and Italy, he had clearly become more enamoured with life in Cuba. While he hadn’t been particularly interested in politics as a child growing up in Italy and Canada, he’d recently developed such an obsession with the speeches of Fidel Castro his friends had begun to tease him about it. After watching Castro deliver one of his famously spellbinding three-hour orations, he told friends he’d never heard anyone speak so passionately about anything. After that, he’d read every Fidel Castro speech he could find, and had even begun to read books of Cuban history.

Fabio now also had a Chinese-Cuban girlfriend and there was talk that he and his father might buy a condo in the Monte Carlo Palace, a proposed condominium project for foreigners in Havana’s elite Miramar district. Since it had been impossible for foreigners to buy real estate in Havana when they’d first begun coming to the city five years before, Giustino, like many other outside entrepreneurs, had turned a room in the Copacabana into his local hotel room-headquarters. He’d chosen the Copacabana, a Brazilian-themed waterfront hotel that had been among the first to be renovated in 1992, because he liked its tropical ambience, its friendly staff, its convenient location—although it nuzzled up against the Atlantic coast, the hotel was still in the middle of the city, an easy commute to almost anywhere—and, of course, its natural saltwater pool that filled directly from the ocean. During their visits to Havana, Giustino had been staying in the hotel while Fabio rented a room in a nearby casa particular to save money.

By 1997, they were spending close to four months a year in Havana. That, in part, was a reflection of their success, but also of the nature of doing business in Cuba. Cuba was not like other countries, Fabio had confided to his brother; in Havana everything took twice as long. Giustino and Fabio began their routine of sales calls at 8 o’clock each morning and scheduled meetings, one after the other, until noon. There were few formal meetings after lunch. That was just the Cuban way of doing business, Fabio explained.

Today, with their last meeting of the morning put on hold, Fabio was eager to hear how Enrico and Francesca had enjoyed their honeymoon in Cuba. He’d already been talking with Enrico, who was worried about his bride. She’d become obsessed with an irrational fear that something “bad” was going to happen to them in Cuba. Fabio would be happy today to remind her that she’d been wrong.

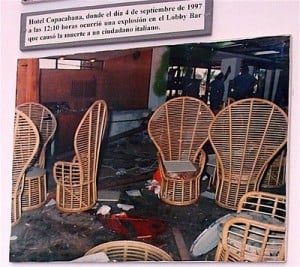

He turned the corner, saw Enrico and Francesca seated at the glassed-in lobby bar waiting for him. He made his way past the tan couches, the high-backed rattan chairs, the potted palms, a canister ashtray. It was time for a drink, a celebration.

Havana, September 4, 1997, 11:40 a.m.

“Señor! Señor!” the boy shouted after the man in the yellow polo shirt, shorts, sandals and a tan baseball cap. “You left something.”

The boy, who was just eight years old, was visiting from Spain with his parents. They were staying at the Triton, another Havana beachfront hotel a kilometer from the Copacabana. This morning, the boy had been playing in the lobby with his babysitter when he noticed a man get up from a seat in the lobby, shrug his blue backpack over his shoulder and walk out of the hotel, leaving a small black notebook behind.

“Señor, señor,” he called again, but the man didn’t look back.

Havana, September 4, 1997, 12:00 p.m.

Roberto Hernández Caballero and his team of State Security investigators were already on their way to the scene of the blast at the Copacabana when they received a second urgent call. There’d been another explosion just up the street at the Hotel Miramar.

Two bombs close together. Just like at the Capri and the Nacional. What did that mean? About the person—or persons—planting the bombs?

Hernández Caballero knew enough to know that the Cuban American National Foundation’s recent statement to the Miami press suggesting the bombs were signs of some sort of internal rebellion was self-serving claptrap. It was far more likely CANF itself was behind the whole thing.

But Hernández Caballero knew investigations started at the bottom. In order to find out who was behind the bombs, he would first have to figure out who was planting them.

In the four months since the Aché explosion, four more had gone off and another had been discovered and defused. Two weeks ago, the most recent explosion occurred at the Sol Palmeras, a hotel in the resort area of Varadero. It was the first blast outside Havana, but it was still clearly targeted at the tourist industry. Was that bombing connected to the others?

In June, immigration officials arrested a Florida woman who claimed she’d come to Cuba to visit her brother. Authorities found traces of C-4 in her handbag, but hadn’t been able to connect it to any of the bombings.

Then in late July, police had responded to a report of an explosion in the highway tunnel leading into downtown Havana. It turned out to have been a false alarm—just a stupid German tourist setting off a firecracker—but even that had ratcheted up tensions in a city wracked by rumor.

Cuban authorities weren’t saying much publicly about the bombings. At first they denied they’d even happened. When the blasts at the Capri and Nacional forced them to acknowledge the obvious, officials did their best to minimize their significance. And no wonder. Would tourists come to Cuba if they thought there was a chance they’d be blown to bits?

So far, luckily, none had. But…

Another urgent call. Another explosion. This one a little further up the street from the first two. At the Triton. Hernández decided he would go to the Triton while the rest of his team fanned out to the Copacabana and the Chateau Miramar. It was going to be a long day.

Havana, September 4, 12:30 p.m.

Fabio dead? How could that be?

Giustino had been resting in his hotel room when he’d heard a deafening noise from somewhere below. A few minutes later, the receptionist telephoned him urgently from the hotel lobby. There’d been an explosion. His son had been wounded. He was being whisked by ambulance to the Clínica Central Cira García, the closest hospital.

Giustino rushed downstairs, past the shattered remains of the lobby bar past the overturned furniture, past the spot where the still wet puddle of his son’s bright-red blood stained the dark green carpet.

The journey to the hospital was a blur, the news there as unexpected as it was incomprehensible.

Fabio was dead, the doctor explained. He had died almost instantly, killed by a sharp piece of shrapnel from the blast. The projectile had ripped into his throat, slicing a major artery.

Venezuela, September 5, 1997

“Paco,” the caller demanded, “are you up to date on all this?”

Paco was Francisco Pimentel, a Cuban-born Venezuelan businessman with close connections to Venezuela’s secret police. During the early seventies, he’d become friends with Luis Posada. The two men had remained close. Posada was calling today to update him on his latest success.

“You have no idea,” Posada gloated. “Three in a row in three hotels in Miramar, all synchronized and with no chance of them detecting the envoy.” Posada hadn’t yet heard the news of Cruz León’s arrest. “And this is just starting. I promise you that several more envoys are on their way to Cuba to carry out new actions…

This is really fierce,” Posada gloated.

Excerpted from What Lies Across the Water: The Real Story of the Cuban Five.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books