This column originally appeared in the Halifax Examiner July 2, 2o18.

My Examiner column last week seemed to set off a modest Twitter tempest, mostly because its subject, Coun. Shawn Cleary, chose to respond to what I wrote and didn’t write (even when he didn’t seem to realize I’d written it); and then to respond in scattershot kind to various readers and constituents, who had taken umbrage at his umbrage.

After a while, Examiner Editor Tim Bousquet, who’d been drawn into the mess, thanks to a personal/professional attack by Cleary (who may or may not have thought Tim was the author of the offending piece when he pounced) freed my original column from its paywall so non-subscribers could at least know what they’d been debating back before the column ceased being relevant to whatever they were now debating.

In other words, a typical day on social media.

I won’t try to respond to all of it, but there are a couple of journalism-related points Cleary raised that do require a response.

At one point early on in the social media bun fight, Cleary tweeted: “From which journalism school did you graduate?” And then followed that with a dismissive: “Journalists do journalism. Non-journalists do ‘citizen journalism,’ blogs, opinions, etc. There are skills of balance, ethics, standards one learns in j-school.”

In coming to my defence in his Morning File column the next day, Tim sought to point out my own credentials: “Understand that Kimber is a long-time reporter and not just a Journalism school graduate but also a Journalism school instructor.”

Uh… Actually, that’s not completely true.

I never attended Journalism school, never earned a degree of any sort until I was in my fifties. But that’s another story.

Somewhere along that path, I landed a one-off gig teaching a magazine writing course at King’s J-School and parlayed that into more than 30 years as a fulltime Journalism prof — the best job I’ve ever had. Yet another story for another day…

As a professor, I’ve tried to channel the lessons I learned from Fillmore, Bruce and others in teaching my own students.

If I had it to do over again, however, I would have chosen to go to Journalism school. Students in J-School today learn more in one year — and in a more organized, thoughtful way — than I was able to pick up in my first decade and more in the “real world.”

That said, I would never make the case that Journalism schools should ever be the only way journalists become journalists, or that all journalists should be licenced.

Journalism is a generalist’s game. If you have curiosity, a determination to discover the facts, even the ones that don’t match your pre-conceived notions, and a passion for telling stories, there are — and should always be — many ways to learn journalism’s specific, ever evolving skills as well as its unchanging ethics and standards. Journalism is a house with many doors in.

Many of the citizen journalists Cleary derides are, in fact, professionally trained journalism grads who do excellent work; many mainstream journalists, particularly those of us who came of age in an earlier, apprenticeship age, learned to do by doing, but are still capable of excellent work.

It isn’t about where you learned, but how well you learned.

At some point in last week’s Twitter torrent, Cleary decided to up the ante, arguing I’d never contacted him before writing my column about him. “In the interest of actual journalism,” he tweeted, “you might think about checking with the source.”

It’s an interesting argument, but it generally misunderstands the role of the columnist in contemporary journalism. Or Cleary’s own role as a public person with a public record.

There was a time — and I lament its passing — when most columnists were full-time employees of the newspapers they wrote for, and were expected to be both shoe-leather reporters and also to have, and express, opinions based on their reporting. That’s much rarer today.

Most columnists, including me, are freelancers. We’re expected, in our columns, to articulate an opinion informed by research, sometimes from personal interviews but often from publicly available news reports, records and documents. (In the era of the internet, of course, much is available publicly, and it is much easier to attribute those sources so interested readers can check them out for themselves.)

I don’t want to imply I don’t do interviews. I do. I spent two hours recently with Pamela Yates, the psychologist who’d been unfairly turned down for a licence by the Nova Scotia Board of Examiners in Psychology, the all-powerful, self-regulating regulator of the psychology profession in the province. I followed up the interview with email questions and a back-and-forth correspondence. I read official documents and various court decisions about the case before I wrote my column.

Armco is proposing to build a see-through building at the corner of Quinpool Road and Robie Street.

In the case of the Cleary column, however, my interest had been piqued by something he said publicly following a council vote last month to approve a controversial 25-storey tower that violated not only existing neighbourhood height restrictions but proposed requirements in a new draft centre plan intended to guide future development.

“We don’t build buildings because of public opinion,” Cleary said after the vote. “We build them for good planning… And so I think this is a good thing for us… In terms of the design, I think we’ve mitigated most of the concerns…”

Clery’s comments were a matter of public record. I didn’t need to ask him to repeat them.

But, given various staff reports opposing the developer’s demands for exemptions and the significant and thoughtful opposition to the project, Cleary’s comments raised questions for me. I knew he’d long been a vocal supporter of the development in spite of that public opposition. I also knew — it had been publicly reported and acknowledged — Cleary was personal and political friends with the developer’s spokesperson.

The arguments I wanted to make were that we need campaign finance rules to end what Cleary himself had once called a “wild west,” in which developers have free rein to donate as much as they want to candidates of their choosing and, secondly, that we need a lobbyists registry to prevent developers from unfettered — and potentially underhanded — access to elected officials.

When I did my research — I did do research — I discovered a few interesting things. During the 2016 election campaign, Cleary himself had said he would not accept donations from developers, and there is no record of him accepting money from any major developer. (His losing opponent in that campaign would beg to differ; Linda Mosher’s campaign manager has claimed at least one of the “individuals” Cleary accepted money from was a small developer who’d lobbied the previous council for an approval, one which Mosher significantly had voted against.)

When I contacted City Hall spokesperson Brendan Elliott to determine the status of the current council’s consideration of campaign finance reform and legislation to create a lobbyists’ registry, he quickly emailed back information, including the fact Cleary is one of the councillors pushing for the lobbyists’ registry.

While none of that changed my view about Cleary’s over-the-top defence of council’s decision or undermined my argument that Halifax needs campaign finance reform and a lobbyists’ registry with teeth, it is relevant information readers had a right to know.

So I included it. It’s what I think of as that “balance, ethics, standards one learns in j-school…” Or in journalism. Or in life.

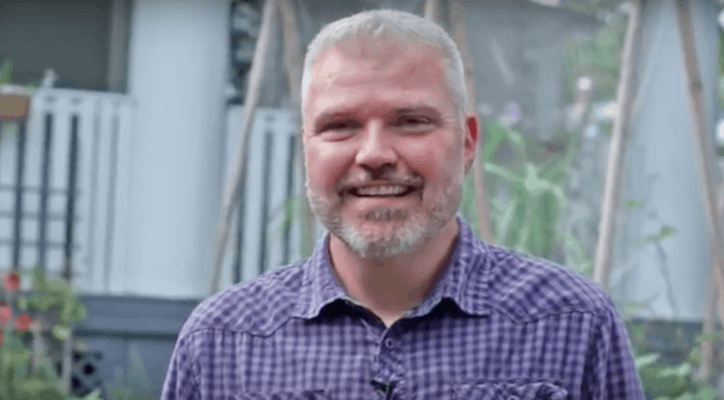

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books