Whatever Happened to the Class of ’67? With Queen Elizabeth High School about to become history, Coast Senior Feature Writer Stephen Kimber — QE Class of ’67 — set out to rediscover some of his own. Whatever happened to his classmates? Did high school change their lives? Did it even matter?

***

Address to the Graduates

Queen Elizabeth High School

June 1967

My first memory from my high school days isn’t mine — or at least it isn’t from my high school days. It is from September of 1967, three months after I graduated from Queen Elizabeth High School. I was a freshman at Dalhousie University. One bright fall afternoon, I drove the few blocks north in my battered, puke-green, ’61 VW Beetle to visit my alma mater. Ostensibly, I had come to meet my then-girlfriend, Martha MacDonald, who was a year younger and still attending Grade 12. But I was there too to lord my newly acquired college-boy sophistication over those I had left behind. Did I really wear my new black-and-gold Dal jacket? Of course. Did I tell anyone how out of place I felt at university? Probably not.

It didn’t take more than a glance to realize this was no longer my Queen Elizabeth High School. In my high school, the boys wore ties. If you could not afford, or forgot, or chose not wear one, one would be provided for you from the hideous collection the principal, Len Hannon, kept in his desk drawer for anyone who failed to obey rules that needed — and received — no explanation. The height of rebellion in my high school was to wear a cowboy string tie — proof not only of our lack of political sophistication but also, unfortunately, of our fashion sense.

In this new school I did not recognize, no one wore ties. Many boys sported previously-verboten facial hair, some wore jeans. So did a few girls! In my high school, Miss Blois, the vice principal, trolled the hallways with her measuring tape, checking girls’ hemlines and ordering any girl who showed too much feminine flesh to go home and change into something more appropriate. Not pants. Certainly not jeans.

On that fine Fall day in 1967, however, all those girlish legs that were not encased in some marvelously form-fitting denim were on glorious, fading-summer-tan display in the hallways of a school that bore only bricks-and-mortar resemblance to the one I’d so recently left.

That, at least, is how I remember it.

Tonight, when I remind my then-girlfriend-and-still-friend, Dr. Martha MacDonald, now Professor of Economics at Saint Mary’s University, about all of that, her recollection is not quite the same. “Girls still weren’t allowed to wear pants,” she tells me.

She could be right. I sometimes think I spent so much of my youth making up my life I’m no longer sure which memories are real and which imagined. Or else, I’m just getting old.

We are standing tonight at the edge of the dance floor in a cavernous room that has been tarted up to resemble the generic school gym of a thousand dances past. Legendary radio deejay Frank Cameron is off to one side, spinning Beach Boys and Beatles songs like it really is 1967.

But the actual backdrop for this mental meander through memory lane is a drab, concrete-and-steel multipurpose room at the north end of the Halifax Forum complex. This room did not exist in 1967.

But the Forum did. QE used to play hockey here on winter Friday nights. The most anticipated games were always between QE, the peninsular “Protestant-and-other” high school, and St. Pat’s, our Catholic cross-street rivals. QE lost most of those on-ice encounters. But not necessarily the ones in the stands. I remember the night Peter Udle — QE football star and chair of a newly formed school spirit committee — handed me his false teeth so he could wade into a melee in the stands. I was proud to have been asked to do my small part for school spirit.

Peter’s name is not on the list of those attending this weekend’s Last Chance QE Reunion. This open casting-call reunion is for everyone who attended the school, an opportunity for the 50,000 or so Halifax teenagers who played out their personal coming-of-age rituals in its hallways from 1943 to 2007 to say one final, fond farewell to their school — and their youth — before it is bulldozed into history.

Though more than 800 alumni have traveled from as far away as Turkey, Australia and China, Peter is not the only grad from my era missing. Just 20 members of my 323-strong Class of ’67 have signed up, even though 2007 is, technically, the 40th anniversary of our graduation.

Shouldn’t that have been an occasion?

Is that my fault?

In 1966-67, I was QE’s Head Boy, that strange British-sounding euphemism the school used to describe the president of its students’ council. In those days, at least if you believe the Elizabethan, the school yearbook, I was the “school’s hardest worker.” Should I have organized our reunion? But that same yearbook also says my goal was “to eventually become an active politician.” Did I really say that? Did I mean it? No matter. I am no longer that person — if I ever was — and I take no responsibility for his failure of alumni spirit.

Most of us did not become the people we imagined we would back then.

Our Class of 1967 includes teachers, social workers, entrepreneurs, doctors and, of course, lawyers. Even disgraced lawyers. Cameron Rhindress, a guitarist in a garage band I briefly mismanaged back in high school, was suspended from practicing law for a year in 2003 for professional misconduct.

There is at least one dentist, a navy captain, a former lieutenant-governor’s consort, some secretaries, lots of bureaucrats, a couple of journalists and insurance salesmen, Nova Scotia’s Senior Representative in Ottawa, a diplomat, a real estate developer, random real estate agents and even a software developer.

John McFetridge, a self-described “dork” in high school when there was still no such thing as software to develop, ended up making his fortune and fame as one of the original creators of the hugely successful Corel Draw program.

Our class can even lay claim to having produced both a professional rock musician and a professional opera singer.

Pam Marsh, whose stated goal in the yearbook was “to get to a surf board on Virginia Beach,” and whose backup plan involved studying “lab technology at the Institute of Technology,” ended up as a member of Everyday People, a popular Canadian seventies rock group. Pam still performs regularly.

Greg Servant — now Dr. Gregory Servant, opera singer and Chair of the Music Department at Dalhousie University — was another a member of that nameless Grade 10 garage band I mismanaged. Mismanaged? At one point, I suggested Greg not sing lead because his voice wasn’t… well, good enough… Greg now says the fact he stopped pushing his voice singing rock and roll — he did play organ in another much more successful high school rock band — probably saved his voice for when he discovered his passion for opera in university a few years later. I like to believe I played my small part in his career.

Greg isn’t at the reunion tonight. “My daughter, who’s very big into Facebook, thinks it strange I don’t have any interest in reconnecting with people I went to high school with,” Greg told me before the reunion, “but I don’t.”

Pam Marsh isn’t either either. Neither is Cam Rhindress. Or John McFetridge, though he tells me later he would have flown up from his home in Florida if he’d realized it was happening.

Jimmy Spatz — aka Jim Spatz, president of Southwest Properties Limited, developer of the award-winning Bishop’s Landing and over $100 million worth of other real estate projects, winner of the 2002 Atlantic Canada Entrepreneur of the Year Award, member of the Nova Scotia Business Hall of Fame and, of course, the Class of 1967 — says he thought briefly about attending, but the reunion happened to coincide with visiting day at the Quebec summer camp one of his children is attending, “so that took the decision out of my hands.” He doesn’t sound disappointed.

Nick Pittas, now Director of the Nova Scotia Securities Commission and another Class of ’67 grad — who remembers high school as the “the first and only time I was a somebody” — told me he would be on vacation with his family.

Hetty Van Gurp, the President of Peaceful Schools International, an anti-bullying organization she founded in 2001 (Time Magazine named her one of its Canadian heroes of the year in 2006, as did Reader’s Digest in 2007) won’t be coming either. “The closure of QE does stir up some memories,” she’d emailed me, “but I can’t really say they are too wonderful.”

So why am I here? I guess I am at this reunion for all sorts of reasons. Nostalgia, for starters. I have mostly good memories of my high school years. Curiosity. I’d like to know what happened to the members of my Class of ’67 (though it is clear I’ll have do more than attend this reunion to discover that). And, of course, that inexplicable, ill-advised desire — after 40 years — to understand what it all meant in the greater scheme of things.

Did — does — high school matter?

“I’m not sure,” Martha says finally. She has been thinking, not about the cosmic questions in my head, but about whether girls were allowed to wear pants. “I don’t think so, but it’s hard to remember. It was a long time ago.”

It was.

“It is astonishing to realize that 1967 is as far away in time to 17-year-olds today as 1927 was to me back then.”

— Margaret Wente

I used to believe there was something unique about the total transformation I experienced returning to QE in that fall of 1967. Halifax was then such a backwater in the North American cultural mainstream I just assumed the sixties simply arrived here later than elsewhere. I’m no longer so sure. My wife, who grew up on the outskirts of New York City and completed high school the same year I did, had a similar experience. So did Margaret Wente, the Globe and Mail columnist who graduated from a Toronto high school in 1967. She wrote recently about that summer as a “watershed” in her life.

Even after it dawned on me that my experience probably wasn’t just a Halifax phenomenon, I still assumed — in my admittedly, annoyingly, we-were-more-special, baby-boomer way — that it must have had to do with the tumultuously transformative sixties, specifically with that seminal year of 1967, which was so important because… well, because I was there.

But that, in a way, is the point.

High school — everyone’s — seems unique and uniquely important when you’re inside it. High school is a strange and mysterious time. When you’re in the muddling middle of it all, you feel like you must be the only person who has ever — could ever — experience the excruciatingly, sweetly painful joy, tears, fears, horrors, loves, lusts, secrets, surprises, doubts of it all. You imagine — and, Lord knows, popular culture reinforces the notion — that high school must bend, twist, spin, shape and change you, that it will matter in the cosmic arc of your life.

But does it?

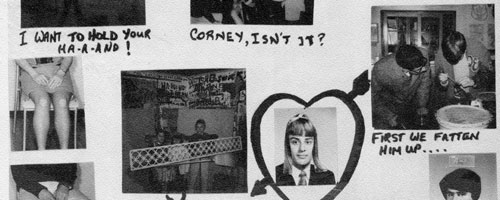

When I leaf through my high school yearbook now and look at all the faded-ink greetings — “Friends Forever!!” — from people I haven’t seen since graduation, I wonder: Whatever happened to that person? Or worse. Who is that person?

I thought I knew everyone back then. I was, after all, the Head Boy. If I had come from the north end of Halifax — in those days, QE was divided along geographic fault lines, which also reflected seismic economic, class and race divisions — my first cousin, Nancy Kimber, the Head Girl, had grown up in the south end. Her younger sister, Trish, was a cheerleader and member of the student council. Our other cousin, David, from Westmount school in the west end, was the editor of Beth’s News and Views, the school newspaper. How could I not know everyone worth knowing?

Flipping through the pages of the yearbook now, I realize what a conceit that was. I look at the names and accompanying scrubbed-face photographs, and read the grad class write-ups. Everyone, it seemed, was “lively,” “good-humoured,” “fun-loving.” Or else they were “serious,” “conscientious,” “one of the quieter members of the class.” Even the quiet types, of course, “enjoyed a good joke now and then.” Even staring, I find it difficult to connect some of the photos with … well, anything at all.

Michael Leir? I should have some memory of him. The yearbook says he was one of the “leading pre-class conversationalists” and that he had “endless wit.” Michael Leir’s Wikipedia entry doesn’t mention those traits. It begins: “Michael Leir (born 1949) is the current Canadian High Commissioner to Australia.” How could I not remember someone who grew up to become not only a diplomat but also the “lead Canadian lawyer” in the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement?

The truth is I didn’t really know much more about even those I thought I knew well at the time. I didn’t know, for example, that one of the reasons Hetty Van Gurp never seemed to participate in extra-curricular activities in high school was that she was being abused — physically and emotionally — by her father. “I was always frightened of getting into trouble with my father, of saying the wrong thing,” she says now. “He didn’t allow us to play sports or join any groups.”

I also didn’t know that Hetty had been born in Holland, and that she didn’t know a word of English when she started school. I only learned those facts many years later when I interviewed her in 1994 for a story about the League of Peaceful Schools.

My lack of knowledge about Hetty’s personal history reflects, in part, the reality that when you’re young, there is no past or future, there is only the present. But there was probably more to it then. If I remember correctly, none of those few students who had come from elsewhere — from Estonia, Cyprus, Greece, Germany or wherever — talked about their cultural heritage. In those days — before multiculturalism and diversity and differently-abled — the goal was to fit in, to keep any differences to yourself, and hope no one noticed.

Ironically, most of us didn’t; we all were too busy trying to fit in too.

Today, John McFetridge, who still does computer consulting, describes himself as “outgoing. I talk to groups, I love partying.” When he was the president of the Ottawa Tennis Club a few years back, the Ottawa Citizen described him as a “bon vivant. ”But back in high school, “I classified myself as a dork socially, compared to everyone else.” McFetridge found nothing about high school — not even being on the hockey and football teams — could make up for his sometimes painful stutter. “You can imagine what it was like asking a girl to go out with you,” he says. He pauses. “High school wasn’t one of the highlights of my life.”

Perhaps to compensate, McFetridge, who did very well academically, hung out with what he politely calls a “less studious crowd.” Which is to say me and my cousin David and our friends. I think I bought my first car — that puke-green VW — from John. (Or did he buy it from me? Funny, the things you can’t remember.) I do remember we teased John unmercifully about his speech impediment; we thought we were funny. “It wasn’t so bad,” he reassures me now. I wish.

Jim Spatz didn’t quite fit in either. “I was sort of a nerdy kid. In the social pecking order of high school, one of the best things to be is a great athlete. And I wasn’t.” Jim compensated by skipping classes and hanging out at the Cue and Cushion, or another pool hall on Fenwick Street with a bunch of guys who also weren’t focused on getting good marks. “In high school,” he jokes, “I improved my skills at playing pool.”

Fitting in was harder if you were black, of course. There were only a half dozen black faces in the sea of white at my 1967 graduation, and I will confess to having had little more than a hallway-hello, nodding acquaintance with any of them.

For others, fitting in may have appeared easier, but must have been at least as hard.

Hetty Van Gurp says her “only fond memory” of high school involved Grade 12 Biology when the teacher allowed her and two other bright students, Marija Dambergs and Paul Coulstring, “to go off somewhere in the bowels of the school and read Scientific American instead of going to class. That was fun,” she says. “I remember I always admired the way Paul Coulstring dressed. He wore these nice pink shirts.”

Ah, yes, Paul Coulstring… I remember Paul too. He was funny, fun-loving, a better dresser than most of us, a good dancer too. There was invariably a gaggle of girls around him.

It isn’t just that I didn’t realize he was gay at the time; the thought didn’t occur to me. I clearly knew there were homosexuals, I just never imagined I actually knew someone who was gay. I can’t imagine now how difficult it must have been for Paul — and for others too — to hide that part of themselves from the world.

Although Paul went on to serve as a Halifax school teacher for 18 years — since he was one of my older son’s favourite teachers, inspiring his love of English, I probably exchanged pleasantries with him at occasional parent-teacher functions — I only finally realized Paul was gay when I read his obituary in the newspaper. It was 1991. The newspaper didn’t mention homosexuality or AIDs, of course, but by then I could read between the lines of his “longtime companion Ron” and the fact that donations could be made to the VG Hospital’s hospice memorial fund. Paul was 42.

He was not the only one to die before his time, not even the only member of my Class of ’67 to die of AIDS-related causes.

Death even happened back in high school.

Kathie Beeston (née Kent) remembers meeting a “cool guy” named Alfie Wilson on the school’s New York trip in Grade 10. They dated on and off through Grade 11. Alfie was “a fun person with a great sense of humour. He was also a great dancer.” Even today, she tells me from her home in Ottawa — she isn’t at this reunion either — she can’t listen to Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman” without remembering how she danced to it with Alfie at Twixteen, the popular Friday night dances at the YMCA.

But Alfie was also a guy’s guy, a little wild, more fond in the end of hanging out with his friends than in having a girlfriend. In the summer between Grade 11 and 12, he and Kathie were no longer dating.

On August 17, 1966 Alfie and three friends were driving in a daddy’s-new-1996-car to Prince Edward Island, a popular teenaged getaway that summer, when their car missed a curve, plunged down an embankment and struck a rock. Three of them, including Alfie —Alfred Flemming Wilson, now forever 17 — were killed.

For many of us, that was the first time we’d smacked up against the sudden death of one of our own. We still remember it.

When you look back, you begin to understand how predictable it was; how even the senseless death of someone like Alfie makes a strange kind of sense — a warning shot across the bow of youth, the message that none of us is really invulnerable.

Is that what high school was all about? A tantalizing glimpse of the possibilities. A sobering dose of the limitations.

Nick Pittas remembers the possibilities. His one year at Queen Elizabeth High was “the best year of my life.”

He’d spent the previous four boarding with a conservative Greek-Cypriot family and going to a school in London, where outsiders were barely tolerated. He’d come to Halifax for his final year of high school in order to live with an older brother who’d just begun grad school at Dal because “I knew I’d be freer.”

He was. Nick was bright, handsome, outgoing. He got involved in the school’s popular model parliament, became the leader of the NDP and — unthinkable then — won a school-wide election to become prime minister. He was also a member of the School’s Reach for the Top team, which won the provincial championship and competed at a nationally televised tournament that summer in Montreal during Expo ’67.

“QEH,” he says now, “was an ego boost.”

When he left high school, he remembers, he thought university would be an extension of high school. His ambition was nothing less than to change the world. “We were going to overturn all that stuff — poverty, racism, sexism — sweep away the debris of society and…” He laughs. “That balloon popped quite quickly.”

It did for a lot of us. We discovered sex, drugs, truth — including the truth that high school was not the world.

Neither was Halifax. In those days, Halifax was comfortable, cosseting and claustrophobically self-contained: it was still possible — probable — to be born, raised, schooled, careered, married, live and die in the same place without ever passing Go or discovering the existence of a world beyond its borders.

Jim Spatz says that, for him, that realization didn’t finally dawn until a few years after he’d started at Dalhousie. He went on a road trip in the summer of 1971 and found himself in Harvard Square in Boston. “I remember standing there looking around and thinking, ‘Fuck, I could have gone here. I should have gone here.”

In the end, Jim doesn’t think high school was significant in what he’s become.

Neither does Nick Pittas. “I do look back on it in a very positive way,” he tells me, “but in the longer term, it was not a huge influence on my life.”

Perhaps that explains why there are so few of us at the reunion.

“I liked high school,” Greg Servant says, “but I have no strong sense of it as having a pivotal place in my life, like university.” After Dal — he was one of the music department’s first graduates — he left for grad school in the United States. Over the next 20 years, his musical career took him to New York, Connecticut, the Amercian Midwest, Switzerland. He returned to Halifax in 1992 when a job came up in the Dal music department. “Our daughter was 10 or 11 at the time, and I wanted to set down roots.”

After he returned, he tells me, he did think briefly about trying to reconnect with some of the people he’d grown up with. “I even got Cameron’s [Rhindress] email address, but I never did anything with it.” He pauses. “The truth is I’m not the same person I was then. That part of my life belongs to someone else.”

Which brings us back to memory.

It has been nearly a month since the reunion. Martha MacDonald and I are having lunch in a small north-end bistro, still reminiscing about high school. She is telling me I don’t remember what I remember. Or at least I misremember it.

She looked it up in her own 1968 Grad yearbook, she says. In the pictures, the boys still wore ties and the girls didn’t wear pants, even in the informal photos.

“Maybe you’re thinking of another year, and another high school girlfriend,” she offers unhelpfully.

Maybe. But it’s my memory and I’m holding on to it. It’s all that’s left of high school.

____

In 1994-95, Stephen Kimber’s older son Matthew — aka hip hop musician Josh Martinez — was QE’s head boy. His younger son Michael was head boy in 2001-02. His daughter Emily was smart enough to attend St. Pat’s and stay far away from student politics.

Hetty Van Gurp: The shy girl

Hetty Van Gurp, a pretty blonde girl from Richmond, a north-end junior high, remembers arriving at Queen Elizabeth High School in the fall of 1964, “excited at the idea I was going to meet new kids from all parts of the city. It was a very Shangri-la-ish view, I suppose.”

And it was dashed very quickly.

“Early in September, I went to one or two football games. I felt completely out of synch with everyone else. I’d see the cheerleaders and wish I could be one of them; I’d see the kids who knew the football players and I wished I could be one of them. But I knew I couldn’t and so, after a few games, I just gave up. After that, I just went to class, did my lessons, went home, did my homework… I felt alone among a thousand other kids.” She pauses. “I don’t have very good memories of high school.”

She is quick to concede her jaundiced view may be, in part, a result of the fact “I was painfully shy then.” Born in Holland, she’d come to Canada with her family as a child and recalls not knowing a single word of English when she started elementary school in Halifax.

But there was more to her unhappiness in high school than simply shyness. Her father was a volatile, unpredictable man who could “one minute be jolly and then the next ranting and raving.” His violence was both physical and emotional. “I was always on edge, frightened of getting into trouble with my father, of saying the wrong thing.”

He regularly railed against those who belonged to high-falutin’ clubs like the Waeg or went on winter ski trips to Wentworth, and wouldn’t allow his children to join school groups or take part in extra-curricular activities.

Hetty wasn’t sure she could fit in anyway. “I knew [my father] was brainwashing,” she says now, “But then I’d look around and I’d think, ‘He’s right.’ It was very blatant then. You knew who was from the north end and who was from the south.” And rarely did the twain ever meet.

He father did allow her to attend her graduation dance, “but I had to be home at midnight. It wasn’t much fun. My dad took all the fun out of everything.”

No wonder she married soon after graduation, to a boy she’d met in high school. No wonder it didn’t last. She married again a few years later, eventually became an elementary school teacher and took the extra time to do what no one had done for her — “finding out about my students and their home life. No teacher ever talked to me about anything even remotely personal. They would look at us and see this idyllic group of siblings who didn’t cause any trouble and that was all they saw. The teachers,” she says now, ”needed to be better trained to know what to pay attention to.”

In 1991, her own adult world was transformed forever — unspeakably tragically and yet, ironically, inspirationally too — when her 14-year-old son Ben was killed by a bully at his Bedford School.

Deciding that “my choice was to make something good of this,” Hetty began small. In her Halifax kindergarten, she created innovative ways to help her students learn that “hands are for helping, not hurting.” The movement slowly spread as other teachers in Nova Scotia and beyond began asking her to conduct workshops to make their classrooms more peaceful.

Today, Hetty van Gurp is the head of Peaceful Schools International, a global anti-bullying organization she founded in 2001. She’s written three books and traveled the world, taking her message to schools from Nova Scotia to Northern Ireland, Serbia to Sierra Leone. Time Magazine named her one of its Canadian heroes of the year in 2006, as did Reader’s Digest in 2007.

Talking with me now on the telephone from a second-floor bedroom office overlooking the river at Annapolis Royal in the house she shares with her third husband, Hetty tries to connect the dots from “feeling alone among a thousand other people my age” in high school to her current life today. She is — “very consciously,” she says — no longer shy nor lacking in self confidence. “I talk to people from all walks of life, rich, poor, doesn’t matter.”

High school? “High school seems like a long time ago.”

“I wish someone had told me the reunion was happening,” John McFetridge says into the phone. In the past few years, he tells me, his connections to Halifax have become more tenuous. He now lives year-round in Gainesville, Florida, as does his younger brother, Ted. In May, they moved their mother from Halifax to a seniors’ home in Ottawa, where John still owns a house.

So he hadn’t heard the news that his old alma mater, Queen Elizabeth High School, was closing its doors forever, or that there was to be a Last Chance Reunion in July.

By the time I track him down, the weekend is already over.

John sounds wistful. “I’ve always enjoyed reunions,” he says.

And well he might.

In high school, John remembers himself as a “dork,” a guy who liked to study and get good marks. He got “some grief for that” from his less academically inclined friends, including me. Worse, he stuttered. We teased him for that too. I can remember one day a bunch of us were cruising along the highway in his old VW — John was driving — when one of the guys in the backseat reached his hands around and clamped them over John’s eyes just for the sport of listening to John stammer out his protests.

To his credit, not ours, John seems not to hold that against any of us. But when I ask him about his overall memories of high school, he answers: “That’s a really interesting question. It definitely isn’t one of the highlights of my life.”

There definitely have been plenty of those since he graduated from QE in 1967. After studying math and chemistry at Dalhousie, he applied and was accepted into med school twice without actually going and even toyed briefly with the idea of taking a master’s degree — “I couldn’t make up my mind” — before moving to Ottawa where he soon landed a job at the University of Ottawa as a systems programmer working on huge IBM mainframe computers. “I loved the feeling of control, of understanding how it worked,” he says now.

When the personal computers made its appearance in the early eighties, “I bought one of the first in Ottawa. It cost me $5,000, had 16K of RAM and a monochrome display.”

Playing around with it, however, he developed software to “fool it into thinking the PC was a mainframe.”

The university — still feeling its way in the relatively new area of technology transfer — allowed him to sell his software, which later created problems for his boss and left his dean “red-faced. But in the end they let me leave — with the software.”

In 1982, John started a business, Simware Incorporated, which became one of Canada’s largest software companies. He soon had 100 employees and sales nudging $20 million a year. “But you remember me?” he says with a laugh. “Not the most structured guy in the world.” By 1987, he’d been bought out of his own company.

Two years later, he joined another fledgling Ottawa software company, Corel, as Director of Technical Development. He is listed as “Developer #5” of Corel Draw, the most successful drawing program in the world. “That was the pinnacle of my career.”

He quit a few years later. “My goal,” he tells me, “was to become a snowbird,” flitting between homes in Ottawa and Florida. But he was still in his early forties and — though he now had the time and money to indulge his “jock” side; he played tennis, skied, windsurfed, rollerbladed and bicycled — he missed the software side of his life.

So he began working with a number of Ottawa computer startups that almost inevitably seemed to get bought out — for a lot of money — and John would move on to the next one. “I’m still involved in the latest dot-Net stuff,” he tells me over the phone, “still on the bleeding edge.”

John, who has been married twice but has no children, says he still has a slight stammer, but notes it’s mostly under control now. “By the time I was in my mid-twenties, it had gotten pretty old. So I sought out some therapies, and they worked.” He laughs. “My brother asks how can someone who was so introverted become so outgoing? Now I love to talk to groups, I love partying.”

Which is one reason he wishes he’d known about the reunion.

Another might simply be that going back might serve as a reminder of how far he’d come.

It was at Queen Elizabeth High School that Greg Servant’s life took one of its most critical turns. But he wasn’t a student at the time.

In fact, it happened a year after his 1967 graduation when Greg, then a freshman at Dalhousie University, won the role of a German soldier in the Dal Glee and Dramatic Society’s production of Oh! What A Lovely War. Since the Rebecca Cohn Auditorium was still just a gleam in its architect’s eye then, the society rented the QE auditorium to stage the annual show.

“In the Christmas Eve scene,” Greg recalls, “I got to sing ‘Silent Night’ in German. And Phil May happened to be in the audience.”

Philip May, the English baritone who’d founded the Dalhousie Opera Workshop three years before, was then in the process of helping organize a new university music department, and he quickly invited Greg to audition.

“That’s when I rediscovered my voice,” Greg says today.

Though he’d taken private singing lessons as a kid — there was no school music program in those days — Greg’s focus during high school was, like most of his contemporaries, rock and roll.

In Grade 10, Greg, along with fellow Westmount junior high grad Cameron Rhindress on guitar and Eric Wood on drums — put together a garage band. I was its manager, though I’m not sure that meant much more at the time than hauling gear and hanging out with the band.

Ironically, no one, including me, though Greg, the future opera singer, should sing lead. His voice was just too… sweet.

Greg laughs. “It is a little ironic,” he concedes, “but it turned out to be a very good thing. I was a bass baritone, which didn’t lend itself to singing rock and roll anyway. And I would have destroyed my voice.”

When their first band didn’t make it out of the garage, Greg and Cameron joined forces with other QE musicians — including Joel Zemel (now a jazz guitarist and teacher), Eddie Kynock and Charlie Phillips (who later ran unsuccessfully for mayor) to form a group known as the End of the Lyne. Greg was the group’s organist.

“The highlight,” he says, “came when we performed for this Thursday evening talent show on CBC-TV. For some reason the cameraman zoomed in on the keyboard, and on this black onyx ring I was wearing. The next day, all the girls were coming up to me. ‘Let me see your ring, Gregory.’” He laughs. “That was exciting.”

The band quickly became a popular staple at school dances, and even at university frat parties — though all the band members were underage.

One night, Greg remembers, they were playing at Domus, the law school frat. “Our contract said we were supposed to play until one. So at one we started packing up our instruments. People started yelling, ‘Come on, guys, keep playing.’ We said, ‘No, the contract’s up.’ And we kept packing. Then this guy, he was a lawyer from some downtown law firm, he pulls out $1,000 in cash and slaps it down on the organ. ‘Keep playing,’ he says. ‘Not a problem,’ we said. And we did.”

When they finally finished performing it was close to dawn. Greg stumbled home to his parents’ house. “I went home and got inside the door and my mother was up waiting for me. ‘Where the heck were you?’” So much for being a rock star.

Greg says the he already knew the rock and roll lifestyle wasn’t for him. So he dropped out around the time he began university. “Once I left, I never saw them again.”

In 1971, Greg became one of the new Dalhousie music department’s first official graduates, and, later, he earned his doctorate in music from the University of Hartford. During his professional career he’s performed more than 50 operatic roles throughout Canada and the United States. He was the featured baritone soloist in a nationally televised PBS performance of Beetoven’s Ninth Symphony and, in 1999, made his New York recital debut at Carnegie Hall.

He’s returned to Halifax in 1992 when “a job came up” in Dal’s music department. By then, he was married to an American and they had a 10-year-old daughter. “I wanted to set down some roots. And I’m glad I did.”

“I don’t remember much about high school,” he tells me now. Did he have a girlfriend, I ask? “I never had a serious girlfriend in high school.” He pauses. “This is going to sound terrible,” he says, “but I can’t recall the name of my prom date. I can see her face but I can’t remember her name.” He laughs. “I liked it when I was there, but I have difficulty now trying to remember it. It really is like it happened to somebody else.”

Nick Pittas now calls Queen Elizabeth High School, circa 1967, “the best year of my life.” But the truth is “the first and only time I was a somebody” almost didn’t happen. It was September of 1966 and he had just arrived in Halifax from Cyprus to live with his older brother and attend school in Halifax.

After four years attending a boys-only, compulsory-school-uniformed grammar school in London while boarding with a by-the-book Greek-Cypriot family, 17-year-old Nick returned home to Cyprus for summer vacation with his family and announced he didn’t want to go back.

His choice, his parents told him, was London or Halifax.

That was not nearly as daunting a prospect as it might have seemed. Back in the fifties, the family had briefly immigrated to Canada, living in Digby for four years, before returning home to Cyprus. “I’d gone to Digby elementary school, so I guess thought of myself as Canadian somehow. Besides, I knew I’d be freer living with my brother than with the family in London.”

On the first day of school, Nick reported to the old school board office at the corner of Sackville and Brunswick Streets to register and find out which high school he should attend.

“Religion?” a school board official asked as he filled in the required form.

“Greek Orthodox,” Nick answered.

The man puzzled for a moment. “Uh,” he said finally, “that’s sort of Catholic, isn’t it?” In those days of religious divide in Halifax (even the office of mayor alternated terms between Protestants and Catholics) St. Patrick’s was the designated high school for the city’s Roman Catholics.

“As soon as I got there and I saw the all-boys classes, I knew this wasn’t for me,” he recalls. “I’d been there, done that. I wanted to meet girls.”

The next day he was at QE.

And it was magical. As a foreign student in London, he’d felt merely “tolerated, there on sufferance.” At blandly whitebread QE, however, he was an exotic. Darkly handsome, he dressed in what he now dismisses as modish “faux Carnaby” fashion — colourful ties, pink shirts, bell-bottomed pants — that only served to remind everyone he’d come from England from whence, in the era of the Beatles and the British invasion, all good things came.

“QEH,” he says now, “was an ego boost.”

When one student tried to recruit him to run for the Liberal Party in the school’s model parliament, Nick demurred. He loved politics — he used to get tickets from his local MP, Margaret Thatcher in her pre-prime ministerial days, to go and watch the British parliament in action — but he fancied himself a change-the-world socialist and told the young recruiter he thought he’d be more ideologically comfortable running for the NDP.

“You’ll never get elected running for the NDP,” the young Liberal confidently informed him. (Confession: That same year, I was the campaign manager for the Canadian Reform Party — no, not the later, real one but the one a few of us created that year as the “people’s” alternative to the mainstream parties, mostly so we could say we believed in CRAP.)

“I did win,” Pittas says with a laugh. “And I became prime minister. That was an ego booster too.”

He also became a member of the school’s Reach for the Top team, a kind of more intellectual Trival Pursuit-type competition broadcast on CBC-TV. The team won the provincial championship, which earned it a trip to the national finals in Montreal during Expo ’67. Though they lost there, Nick was chosen to be on the Canadian team that competed against other countries.

Graduating from high school, he remembers now, his ambition was nothing less than to change the world. “We were going to overturn all that stuff — poverty, racism, sexism — sweep away the debris of society and…”

It didn’t work out quite that way.

“That balloon popped quite quickly.” At Dal that fall, he quickly discovered “sex… the counterculture and all that went with that.” Academic life didn’t turn out to be as “glorious” as he’d hoped either. He left after four years, without the degree he’d come for, drifted through Europe until his money ran out and then made his way home to Cyprus where he did his two years service in the Cypriot National Guard. That was enough to convince him he needed to return to Dalhousie to finish what he’d started.

This time though, he managed to complete his political science degree, law school and even landed a job in private practice with a big firm in Halifax. “I did not,” he admits with a laugh, “leave a mark on Nova Scotia law.”

Instead, he eventually returned to London for his masters in law. When he came back to Nova Scotia a few years later, the province was in the process of setting up a new securities commission to regulate business. He’s now its director. “I’ve been there almost 20 years,” he tells me, seeming almost as surprised as me.

Though he says he looks back on high school in a “very positive way,” he doesn’t believe it ended up being a “huge influence on what happened in my life.”

Is he disappointed, I wonder, that he didn’t end up becoming the politician he’d imagined he would be at graduation?

No, he tells me, “I think people who get into politics want to change society, but the truth is politics ain’t about that. It’s about brokering interests. It’s no place for an idealist.”

Now married with two pre-teen daughters he and his wife adopted in China, he worries that high school will not be the same time of innocence it was for him. “It’s much harder now to be idealistic,” he says. He laughs. “Our generation thought we’d never get old. Now we’re like our parents — always talking about the past.”

Meet some of the alumni:

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

Stephen

No idea if this will end up in your inbox but I must tell you that I am very happy to have come across this document. I grew up next door to Cameron and just a few doors down from Greg.

The others have put all the feelings we all experienced post graduation very well. Some of us fell of a cliff after high school and managed to escape the fall unscathed or perhaps better for it….

Thanks

Wayne Jackson

Class 68

Wendy EMENY Iselin…American Airlines…purser/flight attendant person!? Based in Boston circa ’71…Kenny here…I have a note from you, when you broke a limb…!? Thanks for that last kiss…

KR

Another reunion is in order. I came last year to the reunion from Chicago where I work for American Airlines as a purser/flight attendant. please someone in halifax plan an event with DJ, drinks and dancing for classes in the 60’s. Remember Twix Teen ??