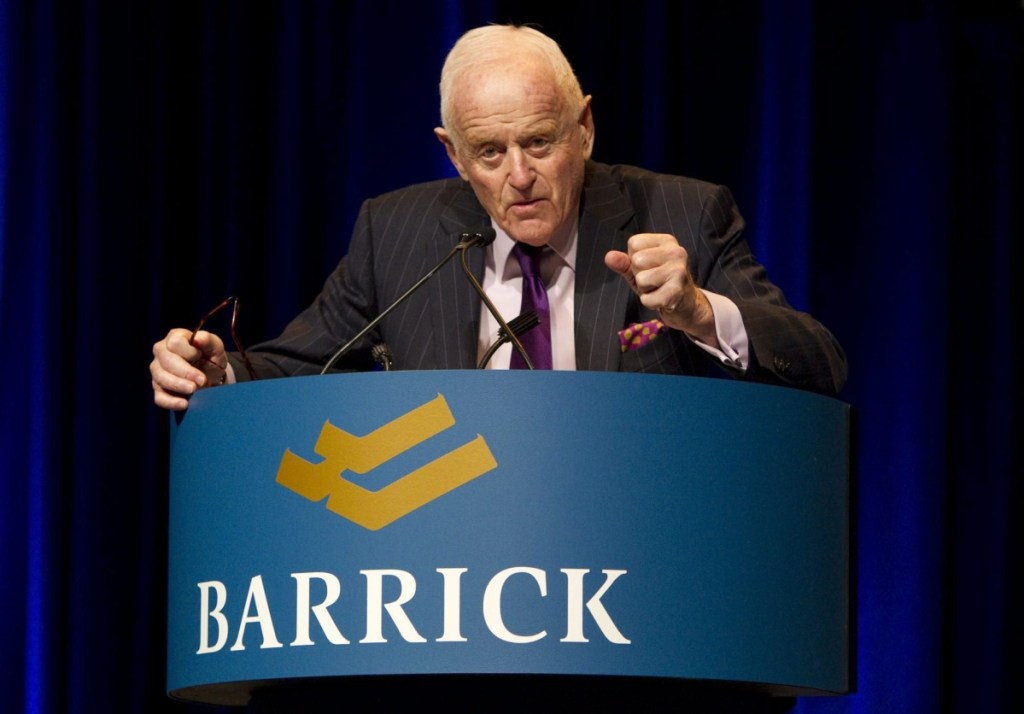

Peter Munk

This column originally appeared in the Halifax Examiner on April 2, 2018.

When Peter Munk died last week at the age of 90, the paeans of praise from the national media were so effusive as to seem over the top.

The Globe and Mail’s3,300-word tributeappeared under the gushing headline: “The Extraordinary Life of a Business Legend, Philanthropist and National Champion.” In The Financial Post, he was remembered as an “entrepreneur with a Midas touch” and a “‘transformative leader’ who embodied Canadian values.” The CBC quoted its own retired business reporter Fred Langan, describing Munk as “a very open, likable person [who] was a charmer and that’s how he got ahead in life and that’s how most people will remember him.”

Most people, though not everyone. Certainly not here in Nova Scotia.

Before we go there, let’s start with the official bio. Peter Munk was born in Budapest in 1927, a Jew who only escaped death in the Holocaust because his wealthy grandfather spent most of his fortune to help more than a dozen family members escape by train to Switzerland in 1944. Four years later, Peter arrived in Toronto at the age of 20, penniless. “Full of ambition and charm, and a natural salesman… he invented a career as a serial entrepreneur.”

According to the stories, Munk launched numerous ventures, including — as the CBC glossed — “a furniture and electronics business,” before founding Barrick Gold in 1983. “Starting with a tiny mine that produced about 3,000 ounces of gold in its first year of operation… [Munk] built it into the world’s biggest gold mining company.”

Although the obituaries generally included a quick feint to his critics, “who said Barrick’s mines around the world had shoddy labour and environmental standards” (among other things, Munk once suggested to his company’s directors that Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet really knew how to run an economy), Munk himself gets the last word. “Someone has got to create and generate wealth,” quoted the CBC.

Perhaps one reason everyone seems so willing to give Munk the benefit of the business doubt is the undisputed reality of how he spread around much of that wealth (aside, of course, from the three homes he owned in Ontario, the others in Paris and Switzerland, the 40-metre yacht tied up at the super-yacht marina he built for the global yacht-rich and fancy free in Montenegro, and…).

Munk donated $300 million to various good causes, including $100 million for the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre in Toronto, $51 million for the Munk School of Global Affairs in Toronto and another $12 million for the also self-titled Munk Debates, which are also — need it be said — headquartered in Toronto.

“The donations,” said the Globe,“can be considered his gifts to Canada, his adopted home and the country whose generosity, fairness and opportunities always amazed him.”

Which brings us, circuitously, back to Nova Scotia and our own Peter Munk connection.

Enter Industrial Estates Ltd., the then-Nova Scotia government’s high stakes economic development gamble that our backwater province could be dragged kicking and screaming into the twentieth century simply by attracting high-flying multinational mega-venture to set up shop here.

As Gilmour giddily explained IEL’s enticements to Munk, the province was super keen to “build the plant… and provide the extra working capital… plus tax holidays, faster depreciation, worker-training grants, and I don’t know what else from federal and local governments… a wild package.”

Wild indeed.

IEL began by ponying up $7.95 million in mortgage financing just to seduce Clairone to set up shop in Pictou, not coincidentally the home of IEL’s president, industrialist Frank Sobey, and trigger federal largesse.

And that’s how it began. Six years later when it all collapsed, the Nova Scotia government had already poured $25 million into Munk’s dream and down the province’s long-term debt drain.

There are any number of explanations for what went wrong. The Globe’s obituary suggested moving production from Toronto to Pictou County — “a poor region with poor infrastructure that was entirely unsuited for manufacturing” — was to blame. Others, including the New York Times,noted Clairtone’s “unsuccessful move into television and poor management of the company’s growth.”

Whatever the actual cause of its collapse, Munk himself would later describe the experience as formative. According to a 2014 article in the Torontoist, for example, Munk once told a reunion of former Clairtone employees: “Everything I’ve been able to achieve afterwards is because of Clairtone. The biggest thing I got from the whole experience is self-confidence. I can achieve anything I set my mind to. We learned the impossible is attainable.”

Which was obviously beneficial for Peter Munk. Not so much for Nova Scotians. With the exception of a donation to his friend Brian Mulroney’s vanity Mulroney Institute at St. Francis Xavier University, Munk’s has been notably absent as a benefactor in Nova Scotia, despite what he acknowledged was the part we’d played in helping him achieve his entrepreneurial dream.

Perhaps there’s a lesson — or should be —in that for us.

A version of this column originally appeared in the Halifax Examiner. To read the latest column, please subscribe.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

Thanks for the historical reminder of economic development gone wild, Stephen. Munk’s callousness towards, and taking advantage of, Stellarton, Pictou County and Nova Scotia was replicated by how he made his mining money. Environmental and occupational health hazards were ignored to make profits, leaving sick communities and workers to pay the price.

As a former resident of Stellarton, it annoys me to see “Pictou” conflated with surrounding towns, or used as a stand-in for all things Pictou County, both good and bad. Pictou is a town (the county seat, if that’s still relevant) in Pictou County. Clairtone was actually in Stellarton, which coincidentally is also the home of the Sobeys. What used to be the Clairtone building is now home to the Zenabis marijuana operation.