Joan Jessome

Let’s start with a question: is Joan Jessome the most hated woman in Nova Scotia?

Google “Joan Jessome” and “hated,” and you’ll get 5,630 hits in less than a Google second. The top three results are news stories following the December 11, 2015, announcement she would be retiring as president of the Nova Scotia Government and General Employees Union (NSGEU).

Usually, when people retire, even your enemies say kind things.

While the word hate doesn’t appear anywhere in any of the news stories, the sentiment fairly oozes out of the over-stuffed Comments sections.

- “Few… have done more to increase the tension between labor and the government than this witch…”

- “She’s destroyed Nova Scotia’s economy and labor relations…”

- “She has made more money in the past 10 years than most of her collective have made in their careers…”

- “Great news! I am so sick of seeing her face and enduring her spoiled attitude and unending greed…”

That Joan Jessome is a lightning rod for vitriol shouldn’t be a total surprise.

She has headed up Nova Scotia’s largest public sector union for the last 17 years — an era when public servants have been increasingly vilified not only by their government employers, but also by many among the public they serve. Under-worked, overpaid, over-perked and over-pensioned uncivil servants. Meanwhile, Joan Jessome has gone head to head, mano a mano, toe to toe on behalf of her members with four different premiers — and won far more often than she has lost.

She’s butted heads with the leaders of rival unions too. Two years ago, after Premier Stephen McNeil tried to gut her militant NSGEU in favour of other, supposedly more pliable public sector unions, Jessome took on both the government and her fellow unionists. She won.

Jessome even had to overcome opposition inside her own union. In 1995, when she first ran for elective office, a “dirty old boys’ club,” as well as skeptical “old-guard” staff insisted Jessome wasn’t experienced enough to hold union office. She won. And again. And again.

Who is this woman so many Nova Scotians love to loath, and others just love? It is worth remembering — as you contemplate the hate — that her 30,000 union members have elected her to be their leader eight consecutive times, the last six by acclamation?

So who is she? And what makes her tick? You may be surprised.

***

Joan Jessome was born in 1958 in New Waterford, the Cape Breton heart of Nova Scotia’s trade union movement, but she didn’t know — or care — about that then. Her father was a union coal miner and occasional moonshiner; her mother baked molasses cookies to hide the smell in case the police came by. Joan was the oldest of their six children. “I was supposed to be the caregiver, and there were great expectations.” She didn’t meet them.

She recalls being bullied in school. “I don’t remember one good day.” She dropped out in Grade 11 at the age of 17. She was, by her own admission, “wild,” when she fell in love with a married man four years her senior named Terry. After she became pregnant, “there was hell to pay.” She sought help from a local parish priest who molested her. She ran away to British Columbia, fell into a depression, overdosed on pills, got sent to a hospital psych ward…

She returned to Cape Breton in time to give birth to her daughter, Shauna, on June 28, 1976. But Joan’s parents refused to let her return home with the baby, so she says she agreed to hand her daughter over to her local church for one month so she could travel to Halifax, land a job, get an apartment and then return to pick up her daughter. Instead, church officials called the police, who issued a warrant for her arrest for desertion.

She arrived in court with no lawyer. Luckily, “the judge took pity on me. He criticized the church for what they’d done.” He asked how much time she needed. “He gave me six weeks.”

She got her child back, but her parents still refused to have anything to do with either of them. “When I went to the funeral of my grandfather,” Joan remembers, “I heard my mother say, ‘I don’t have a daughter named Joan.’ My siblings weren’t allowed to have anything to do with me.”

Suddenly, she was pregnant again. She shrugs. “I was still in love with the guy.” When Terra was born in March 1978, Joan called her mother to let her know she had another grand-daughter. Her mother’s response: “You’ll be happy to know your mother has MS.”

Their estrangement only finally ended 10 months later when Joan’s parents asked her sisters what they wanted for Christmas. They wanted Joan back home.

Incredibly, “we became very tight as a family after that,” Jessome says today. “The kids loved their grandparents; their grandparents loved them.” Joan’s mother even moved in with her and her children in Halifax after Joan’s father died in 1985. But, she admits, “we never talked about what happened.” Joan only finally worked up the courage to talk to her mother about the impact of their estrangement when her mother was on her deathbed in 1992. “She didn’t respond, but I think she heard me.” After her mother died, “I went home and embraced the kids.”

By then, there were three. The youngest, Willena, was born in 1981. Joan and Terry had finally married in 1980. They moved into a Fairview co-op where the kids could have a backyard and good neighbours. Joan taught Brownies. But it was never a marriage made in Ozzie-and-Harriet heaven. Terry, a taxi driver, “wasn’t interested in family life” or paying family bills. “We’d run out of oil. The power would be cut off.” To make ends meet, Joan worked at a convenience store, sold Tupperware and even made and sold X-rated, body-part-shaped chocolates, which she stored in the family freezer. “The kids still laugh about that.”

On her 24th birthday — January 22, 1982 — Joan Jessome considered how her life had turned out. She had become everyone else’s poor, white trash cliché. She had three kids, an unhappy marriage, too little money, not enough education. She smoked too much, ate too much. She wasn’t ready for that to write the story of the rest of her life. “I made a promise to myself. Once the kids were old enough, I would get my education, quit smoking and buy a car.”

She quit smoking in 1986. She landed what seemed like a steady job at the nearby Capitol Stores, working her way up to accounts payable. But, in January 1988, she was laid off. She applied for an EI manpower training course to become a medical secretary, but was turned down. Just before the course began, however, the school called. Someone had dropped out and there was an opening. Was she still interested?

She graduated in May 1989, had stomach-stapling surgery in July 1989, lost weight and began working as a casual medical secretary “all over the place,” juggling temp hours with night and weekend shifts at Shoppers Drug Mart to make ends meet.

When she’d initially decided to get the stomach-stapling surgery, her husband warned her he’d leave her if she did. “I said, ‘OK, and take the kids.’” She laughs. “I knew that was an empty threat. He didn’t want anything to do with kids.” It was the stuttering beginning of the final ending of their marriage. It collapsed for good “in ’92 or ’93.”

By then, however, Joan Jessome had reinvented herself. She became union made.

***

Jessome on the picket line.

“Do you want to come to the local meeting?” a co-worker asked.

“What the hell’s a local?” Joan replied.

It was May 1990, and Joan Jessome was still acclimatizing herself to her new job as a secretary in the Nova Scotia Department of Health. It was her first ever permanent position and it came with benefits, including membership in NSGEU Local 8 (Civil Service). At the time, Jessome didn’t have a clue what that meant, or why it should matter to her.

But she attended her first union meeting with the co-worker. Intrigued, she kept going. That fall, the local president decided to resign, and the chair asked if anyone wanted the job. “No one spoke up, so I did.” She suddenly became the leader of an 800-member local made up of health care, community service and labour department employees.

She had found her place — taking advantage of union leadership and training opportunities — but she would only find her own, full-throated public voice four years later, on an early June night in front of 2,500 noisy protestors at a rally outside Province House. John Savage’s Liberal government had just introduced the Public Sector Workers Wage Bill, which cut the wages of provincial public sector workers by three per cent, and — insult to injury — imposed a three-year wage freeze.

The two-hour rally featured a dozen prominent labour speakers, including Canadian Labour Congress national president Bob White. But the star of the show — according to a news report in the next morning’s Halifax Daily News — was “a provincial civil servant” named Joan Jessome who compared the Savage government to a “cancer” invading people’s lives. “It gets into everything,” she told her fellow protesters. “It doesn’t have any scruples, it doesn’t care if it affects our children or our elderly. It gets right in there and it eats away and it eats away. It’s eaten away our democratic process… So,” Jessome finished with an oratorical call to action, “John Savage and your Liberal government, cancer can be beaten! And we’re going to do it!” The crowd, the newspaper reported, “roared with approval.”

The next year, she ran for second vice president on the union’s provincial executive. Some told her not to. It’s too soon. Others have more experience. She ran anyway, and came first in a field of five candidates. The next year, the first vice president resigned to take a union staff job, so Jessome automatically stepped up to serve out the rest of his two-year term. When she sought re-election at the next convention in 1997, however, the naysayers again said nay. What if something happens to (union president) Dave Peters? You’d automatically succeed him and… well, you’re just a secretary. In a field of three, she won on the first ballot. Two years later, when Peters retired, she won his fulltime job, becoming the first female president in the union’s 42-year history.

Although she acknowledged at the time her gender may have had “a little impact” on her victory — about 70 per cent of the union’s then-13,000 members were women — she insisted to reporters: “I really believe I won the job, not because I’m a woman [but] because the delegates have the faith I can do the job.” That job? “My issue, and my goal, is to bring unity to the union to take on the fights we have to take on.”

Unity wouldn’t be easily achieved. Some among the union executive and staff remained openly hostile. When she fired the union’s executive director — “he was not a good fit [and] the decision was mine to make” — some executive members called for her resignation. She weathered that storm and a subsequent challenge at the next convention. Her leadership would never be openly challenged again.

That may have been because she’d already established a reputation inside and outside the union for taking on those “fights we have to take on.”

Just five months after becoming president, Jessome had presided over a “hair-raising, please-don’t-let-anyone-die,” walkout by the province’s 650 paramedics. Nova Scotia paramedics, who sometimes worked up to 100 hours a week, were among the lowest paid in the country.

After months of fruitless bargaining for a first contract, John Hamm’s freshly minted Conservative government introduced legislation to pre-emptively take away their right to strike. While that legislation was still being debated in the House of Assembly, the paramedics walked away from their ambulances. The standoff only ended 18 hours later after the government agreed to submit the dispute to an arbitrator. That arbitrator eventually awarded the paramedics wage increases of 20 to 99 per cent over three years.

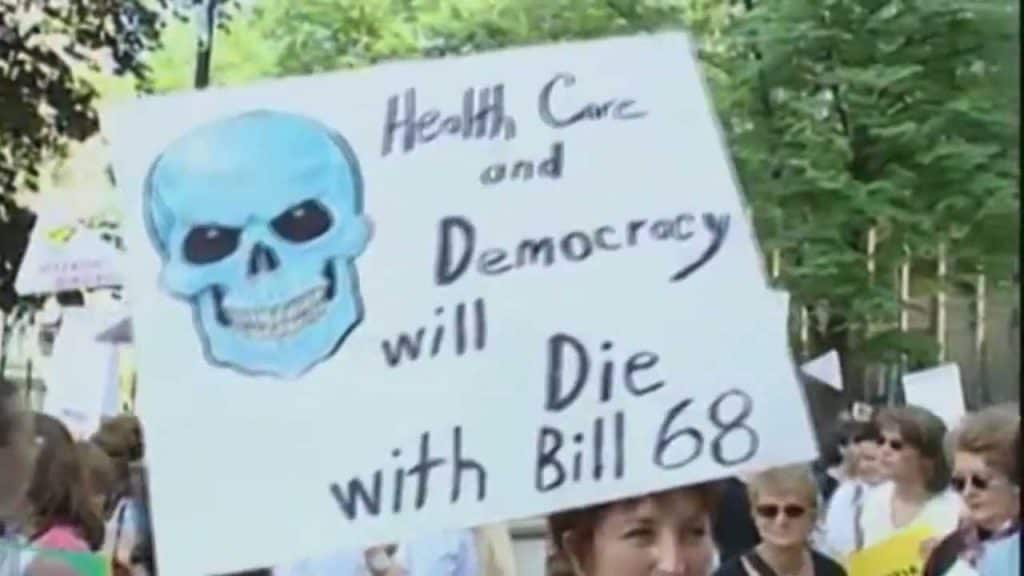

Bill 68 protest.

Two years later, Jessome pushed Hamm back to the brink — and almost over the edge and into the abyss. Hamm had introduced Bill 68, a much broader law to not only ban strikes in the health sector but also allow the government to impose contracts without negotiation or even arbitration, and then bar the courts from reviewing the deals. Despite threats of huge fines for anyone who violated the new law, the unions mounted massive protests and nurses threatened to resign en masse. At the last minute, the government again blinked, signing a deal with the NSGEU and two other unions that effectively killed the legislation.

But not the idea behind it.

It was the beginning of a 15-year-and-counting war of words and laws between a series of financially strapped, neoliberal, austerity governments of all political stripes, each more desperate to cut spending and balance budgets, and a militant public sector union, equally desperate to preserve its members’ hard-won gains in the face of cutbacks, clawbacks and attempts to destroy it.

Most of the time, Jessome has won. “Jessome has a gift for motivating her membership that’s pretty much been unmatched by the governments she’s faced,” acknowledged the business website allnovascotia.com. “At one point she wrangled six straight years of 2.9 per cent pay bumps — from Tory governments no less.”

“Despite our differences, and they were, at times considerable,” allows John Hamm, the Tory premier she wrangled those increases from, “there was a frankness between us. I respected her and I admired her. She always represented her union members very well.”

Darrell Dexter first became friends with Jessome in 1998 when she worked on his first election campaign just as her own union leadership career was beginning. After Dexter became premier in 2009, however, their past friendship was “largely set aside,” he says. “I can sum up Joan’s negotiation style in three words: tough, very tough.”

While ever better contracts for her members may be among Jessome’s most obvious accomplishments as union president, they are not necessarily the most meaningful for the bullied kid who still can’t remember “one good day” at school and who later experienced workplace bullying first hand during her time as a secretary, and even a union leader. “I always had to push back.”

In 2010, the NSGEU officially launched a union-developed Bully-Free Workplace initiative that is still Jessome’s pet project. Offered cost-free to NSGEU workplaces and on a cost-recovery basis for other businesses, the peer-to-peer program has trained over 16,000 workers in Nova Scotia in anti-bullying approaches, and been celebrated as an exemplar at anti-bullying conferences around the world, including in Japan, Denmark and — last month — in New Zealand.

At that point, Joan Jessome confided to colleagues she was ready to call it an NSGEU career and seek new challenges.

Then along came Stephen McNeil.

***

Joan Jessome can be sanguine about most of the politicians she’s stared down. John Hamm was “stubborn,” but there were “no surprises. He was an honourable man.” Rodney MacDonald, his short-lived successor, was “in over his head.” Although she’s still angry with Darrell Dexter’s decision to contract out government jobs to IBM, Jessome, perhaps not surprisingly, has a soft spot for the more labour-friendly Dexter. “Stuff got fixed,” she says.

It didn’t take long for McNeil’s government to change her mind about quitting.

Shortly after he took office, McNeil brought in Bill 30, declaring poorly paid home-care workers an essential public service, making it illegal for them to strike and threatening that, if they didn’t accept the government’s last wage offer, the next one could be worse. Jessome says the union tried to find a compromise. “We said, ‘we can fix this.’ He wasn’t interested.”

Three months later, McNeil smacked down a brief strike of nurses protesting their working conditions by eliminating the right to strike for all health care workers.

Before the union could challenge the law in court, McNeil — ostensibly as part of a move to reduce the number of health care bargaining units — tried to scatter NSGEU members to other unions, not of their choosing, in order to weaken Jessome and the NSGEU. When McNeil’s own mediator-arbitrator refused to go along, the government tried to fire him. But, facing another charter challenge he was likely to lose, McNeil eventually backed down, reluctantly allowing the workers to “remain members of their existing unions.”

McNeil’s scheme seemed to be working until December when the province’s usually docile 9,000 teachers unexpectedly voted 94 per cent to reject the contract, citing what they saw as the McNeil government’s bully-boy tactics. Jessome’s NSGEU, which had reluctantly recommended the government offer to its own members as the slightly lesser of evils, announced it would hold off on its own membership vote until the smoke had cleared. It still hasn’t cleared.

That said, no one really expects the unions will be able to negotiate a significantly better deal. With no prospects for change until at least after the next provincial election, Jessome decided it was finally the right time for someone else to take up the fight.

On December 11, 2014, Joan Jessome announced she was retiring as president of the NSGEU.

***

A month later, she’d changed her mind. She says now she was already having doubts about whether she could make a real difference on an unfamiliar national stage. Besides, she adds, she was facing pressures at home. She’d remarried in 2001, and she and her husband, Winston West, have a blended family of seven children and 17 grandchildren. They didn’t want her moving to Ottawa. “I was hearing it, especially from the grandchildren,” she says.

Not that she’s ready to go quietly into that grandmotherly good night. She’s still just 57, and there’s lots she can do at home beyond leading the NSGEU, perhaps as a champion for bully-free workplaces or as a mental health advocate, both causes close to her heart.

***

Joan Jessome was shopping at the Italian Market in Halifax one recent morning when a woman simply materialized in front of her, holding out a slice of coconut cream pie. “You really can’t say no,” the woman told her, handing her the pie. “This is just a thank you for all you’ve done.”

Joan Jessome knows what people say about her in the comments sections, even though she claims she’s long since stopped reading them. She doesn’t even want to consider what motivates the haters.

But she takes comfort in knowing there are plenty of others—the pie lady, the man whose sister is a nurse who tells her to keep fighting, the stranger who stops her to tell her he loves listening to her, not to forget the thousands of NSGEU members who would still go to war if she asked them to—who aren’t ready for her to retire completely.

“It’s going to be a little scarier on my own, finding my own feet, just being Joan,” she admits, “but I’ve had 25 years on the front lines in this province and I know there is still a real void when it comes to advocacy.”

Loved and/or loathed, Joan Jessome isn’t ready to walk away yet.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

She is the cancer, not Savage.

Great piece, Stephen. Lots there I didn’t know and you put a human face on “the dragon lady”.

Thank you Joan keep going great Job, if people like you don’t do what you do we will be back to the company house and wages that would make it impossible to get out from under.

Excellent lady, great friend , thank you for such a moving story. Being a member of NSGEU for 32 years have watched Joan grow in her passion for what she does and her compassion for whom she does it for, which really is all Nova Scotians who we believe deserve quality public services. Thank you Mr. Kimber. Michelle Dockrill