“‘Truth and Reconciliation’ versus ‘the Murdered and Missing’” was intended to be a serious academic lecture by one of Canada’s most esteemed poets and social justice truth speakers. Somehow it all went wrong.

I don’t know George Elliott Clarke well, but I have known him for a long time. Back in the mid-1980s, before he became what the Globe and Mail recently called “a celebrated Canadian poet,” he was a young wannabe writer earning his actual living as a field worker for the Black United Front, a black advocacy group established in Nova Scotia in the wake of the Black Panthers’ city-shaking visit to Halifax in the late sixties.

At the time, Clarke, who was based in the Annapolis Valley, had been dispatched to Weymouth Falls, a small rural black community in Digby County, to support residents angry about a recent murder case in which a 29-year-old white man named Jeffrey Mullen had been acquitted by an all-white jury of killing a 32-year-old black man named Graham Jarvis.

I was a freelance journalist and I’d gone to Weymouth to interview Clarke and others for a story.

What I remember most about the case itself was court evidence the white man didn’t bother to report Jarvis’ death to the police for several hours because he would have had to walk across his freshly painted floor to get to the telephone. I also remember this infamous quote from John Nichols, the judge in the trial, who told the Toronto Star: “You know what happens when those black guys start drinking.”

I don’t remember much about the specifics of my own interview with Clarke. Perhaps it took place in a bar, or maybe a church hall. What I do remember are the impressions that lingered: George’s big-eyed, full-faced smile, his room-filling laughter and, oh yes, his unwavering determination to fight injustice and racism — both of which he’d already lived more than enough of in his own 25 years of life — wherever he found it.

Clarke couldn’t win the battle for justice in the Jarvis case — no surprise there or then — but spending time in Weymouth did help inspire Clarke’s second book, Whylah Falls, a novel in verse that “immediately established Clarke as a major poetic spokesman for his community,” as the Canadian Encyclopedia puts it. “By turns joyous and sorrowful, rollicking and razor-sharp, the poem recounts the lives of poor Black Canadians in rural southwestern Nova Scotia in the 1930s.” The book, which has never been out of print, inspired a radio drama, a play and even a feature film.

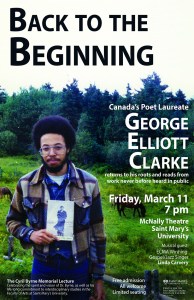

That was the real beginning of Clarke’s illustrious career: he has written 17 collections of poetry, two novels, four plays and a screenplay; won a Governor General’s award for poetry; been Toronto’s poet laureate and Canada’s parliamentary poet laureate; was named to the Order of Canada and the Order of Nova Scotia.

His latest book, Portia White: A Portrait in Words, is about his great aunt, the late opera singer Portia White, who faced racial discrimination but was still “the first African Canadian (and African-Canadian woman) to become an international concert sensation.” Last month, I attended the book’s Halifax launch and listened to Clarke read and be interviewed by CBC Information Morning’s Portia Clark. It was a satisfying evening.

Since I first interviewed him 35 years ago, I’ve occasionally been among the supporting-author cast at literary festivals where Clarke was the star. We’ve also talked from time to time, most recently about his memories of Alexa McDonough, whom he calls his “first teacher,” for a biography I’m writing about the former NDP leader.

My first impressions have never altered, but they have deepened. The George Elliott Clarke I know is generous, compassionate, funny, thoughtful, joyous, intellectual and sometimes joyously intellectually combative. He revels in the discussion of difficult ideas, and will happily engage almost anyone anytime anywhere.

That, I’m guessing, is how Clarke has ended up deep in the messy middle of the latest Great Canadian Literary and Cultural Controversy. What makes the situation worse — and sadder — for those of us who admire him is that much of Clarke’s undoing seems to have been his own doing.

He had been invited to deliver the Woodrow Lloyd Lecture on “‘Truth and Reconciliation’ versus ‘the Murdered and Missing’: Examining Indigenous Experiences of (In)Justice in Four Saskatchewan Poets” later this month at the University of Regina.

At one level, Clarke — a black man who has both Mi’kmaq and Cherokee heritage and has a long and exemplary history not only for social and anti-racist activism but also for literary researching and writing about “murder, punishment, death and hanging through his novels, poems and plays, even through his own family history” — seemed ideally positioned to talk about such issues.

He’d recently delivered a talk at John Cabot University in Rome entitled, “Must Poets Always ‘Hang’ with Murderers?: A Meditation on Poetics and ‘Justice’.” The lecture seems to have been a serious academic attempt to raise the very contemporary question of how we should judge artists: simply by their art, or by their lives, or both.

The full account of his talk on the university’s website is worth reading, but here is the germane section and the anecdote that likely triggered the current controversy, which begins with Clarke’s own statement:

“Yet I was wholly unprepared when a good friend of mine, a poet, got convicted of a murder, 25 years ago, and sentenced to nine years in prison.” Clarke’s friend was an accomplice to murder of an indigenous woman. Clarke highlighted that his friend benefited from white skin privilege. “My friend ended up serving only 3.5 years because of a sexist and racist judge who decided that the victim, an indigenous woman, a sex worker, partly deserved the rape and death at the hands of two young white men.” The victim was “a person of colour just as I am, widely subjected to the variety of racism that I as well suffer.” Clarke argued that the crime committed by his friend was vicious and unpardonable.

“My friend, the accomplice to murder of this woman, is [also] an incredible poet. He is a very fine poet. As now he is in his forties, he is a fairly kind man, who has paid his debt to society, as the saying goes, and so should be left to live his life.” Clarke admitted, nonetheless, as he stressed, it is important to see his friend as both a great poet and as a murderer.

The friend, it turns out, is Steve Kummerfield, who, in 1995, was one of “two white, middle-class, young men [who] lured Pamela George, 28, a single mother who occasionally sold sex to help support her children, outside the city [of Regina], beat her to death and then bragged about it.”

Clarke, who is also a University of Toronto professor of English, did not know this 10 years later in 2005 when he began editing the poetry of Kummerfeld. By then Kummerfield had been released from jail. He eventually changed his name and moved to Mexico.

By the time Clarke learned the details of the murder four months ago, he had already become an admirer of Kummerfield’s work as well as a friend.

The art? Or the artist’s life?

Based on the report of his Rome talk, Clarke himself still seemed to be grappling with that, both intellectually and personally.

But the mere news of his friendship with a man convicted of such an especially brutal and heartless murder, coupled with the possibility Clarke might choose to read from some of Kummerfield’s work as part of his lecture, inevitably triggered, angered and offended many in Regina, especially in the Indigenous community where Kummerfield’s crime — and the apparent lack of a sentence appropriate to it — is still an open wound.

Inside the university, questions were asked: about why Clarke had been invited to speak at all, about who had been consulted, about who knew what about all of this and when. There were complaints, demands his invitation be rescinded, even unfounded doubts expressed about Clarke’s own Indigenous heritage.

CBC News eventually picked up on the story. In early January, its reporter, Bonnie Allen, pieced together a thorough accounting of all the many threads involved, including interviewing Clarke himself.

This is where Clarke seemed to steer his own train off the rails and over a cliff. He could have/should have expressed some understanding for how many in the Indigenous community would feel about the situation. He didn’t, at least not in the published bits of that interview. Instead, like many of us who feel under attack, Clarke came off as defensive. He defended his relationship with Kummerfield:

He said it’s “kind of immaterial” whether or not he knew of Kummerfield’s crime when he began working with him because he may still have chosen to work with him based on an appreciation of his art… “I admire lots of poets, including many who are now long gone, who committed crimes of one sort or another … but who still left behind considerable legacies of excellent poetry for poetry-lovers to enjoy.”

Fair enough.

But he then seemed to send mixed signals about how — or whether — he would incorporate Kummerfield’s work into his lecture. While he told the CBC it was not his plan to discuss any specific cases of murdered or missing Indigenous women in Saskatchewan, but rather to raise “the larger philosophical question of the responses of poets, or non-responses of poets, to questions of grave social consequence,” he then equivocated about including a reading from Kummerfield in his lecture, saying he “may or may not.”

Many of those of us who do even occasional public talks will sympathize with Clarke’s uncertainty. Given that his lecture was then still a month away, he probably hadn’t written it and wouldn’t know exactly what he would — or would not — want to say. But that — based on the CBC report — doesn’t seem to be the explanation Clarke offered.

By then, however, it didn’t matter.

There was more from the interview, and it seemed to get worse with Clarke’s every next soundbite.

- He declared he would not pander to “so-called intellectuals” who wanted to send a “lynch mob” for him just because he had a working relationship with a convicted criminal.

- He lashed out at critics for trying to “weaponize” his talk “to exercise their vindictive feelings.”

- He suggested his critics “just relax” and take the event for what it is: “an academic talk on a serious and grievous matter of social importance.”

By then, of course, relaxing was no longer an option. Clarke had made himself cannon fodder for a social media shitstorm. And we all know what happens when that happens.

Within 24 hours, Clarke himself had wisely canceled his talk. “I never intended to cause such anguish for the family of Pamela George and the Indigenous community, and for that I am truly sorry,” he said in a statement he should have made sooner. “I am a mixed Black and Indigenous writer and scholar, and my advocacy for justice for Indigenous Peoples and People of Colour in Canada must never be in doubt.”

That his reputation was cast into any doubt at all is, in part of course, George Elliott Clarke’s own loose-lipped fault.

But this is also a story about us and our rush-to-judgment cancel culture. Most of us can only aspire to look back on a track record as long and as granite-solid as George Elliott Clarke’s when it comes to serious issues of social and racial justice. Before we are too quick, too harsh in our judgement, we all — George Elliott Clarke included — need to step back, take a breath and ask ourselves how we should factor one misstep into a life and career so well lived.

This column first appeared in the Halifax Examiner January 13, 2020.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

Excellent column. Thanks. But I’m confused about Clarke’s reference in his Rome lecture: “I was totally unprepared when a good friend of mine, a poet, got convicted 25 years ago of a murder and sentenced to nine years in prison … .”

Did he know him that far back? Interesting.