Halifax

December 17, 2014

Inside the second-floor King’s College boardroom, close to a dozen of us huddled around a meeting table, wake-up coffees in hand, listening while our university’s director of finance walked us through her Powerpoint presentation of bad news we already knew, but in far more excruciating detail than any of us wanted to know.

We were in the trough of an existential crisis, struggling with a North American-wide decline in enrolments in liberal arts and journalism, programs we specialized in. I’d spent the last year on a succession of sub-committees, ad hoc working groups, and now this College Task Force “to ensure… the institution is financially sustainable on an ongoing basis.” The projections on the screen starkly showcased the crisis. “Given our expected beginning cash balance at the end of 2014-15 and those assumptions,” the school’s finance director explained, “our deficit by the end of 2015-16 will rise to—”

“Hi Hey Hello…”

My iPhone was ringing! Worse, the phone was in my backpack. Worst, my backpack was on a chair on the other side of the room. Embarrassed, I scrambled to find it. My ringtone was the chorus from one of my hip-hop-musician son’s songs. Why not? Samsung thought the song’s lyrics so phone-perfect they’d built a slick, Hollywood-style video around them to advertise their Galaxy 4 phone. Normally, I found a way to work that father-brag into any conversation when my phone rang. But this did not seem the time or place.

“I just want to say hello.

And hear your voice. And watch you talk.

And smell the breeze as you come across.

Hi Hey Hello.”

I found the phone, stole a quick glance at the screen. The call was from Alicia Jrapko, the American head of the International Committee for the Freedom of the Cuban 5. I quickly pressed “Decline.”

“Sorry, sorry,” I said to my bemused colleagues.

I knew why Alicia was calling. We’d been emailing about my involvement in an event she was planning for Washington in February. It was part of the ongoing, never-ending effort to free three members of the Cuban Five still in prison in the United States. I would call her back. I didn’t wonder why Alicia, who is based in California, would be calling me at five in the morning her time.

I shoved the phone in my pocket, returned to my seat at the table. Thirty seconds later—

“Hi Hey—”

Damn! I’d forgotten to set the phone to vibrate. I hit “Decline” and flipped the ringer switch. But a few seconds later, I heard the distinctive ping of a text message. And another. And another. I had no idea how to turn off text alerts! Then the phone started vibrating. Another call. I had to turn it completely off.

More apologies, fewer bemused faces. As I fumbled with the phone, I noticed I had 23 unread emails! We’d been meeting for less than half an hour? As I reached for the “slide-to-power-off” button, I snuck a quick look at one:

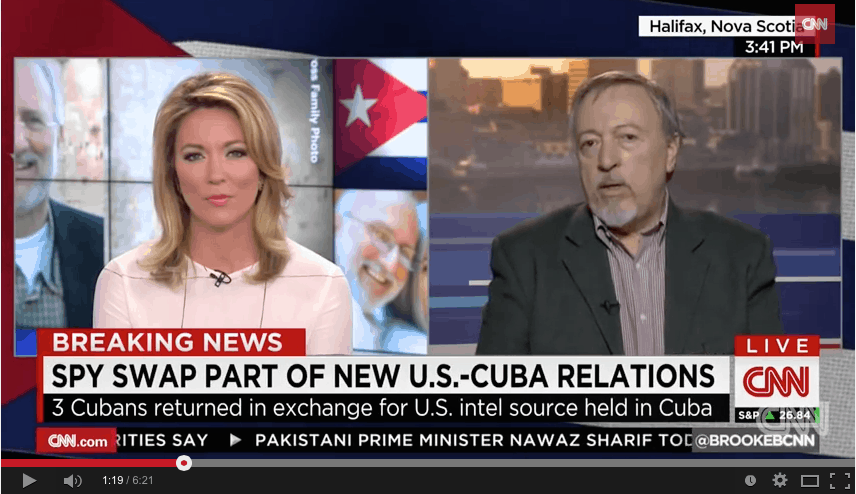

“PLEASE READ: CNN Interview Request for today

Hi Stephen — I am a producer for CNN. In light of Alan Gross’ release—”

The screen went blank. What the—?!

The Five — two had already been released after serving full sentences — were members of a Cuban intelligence network arrested in Florida in 1998. I’d written a book about their case. The Cuban government had made it clear it would not release Gross unless its men were freed too. But the American government insisted, with equal vehemence, it would never swap Cuban “spies” for Alan Gross, a “humanitarian do-gooder” held “hostage” since 2009 for being in “the wrong place at the wrong time.”

The fact the American narrative didn’t fit the facts didn’t matter. The political reality was both countries had painted themselves into negotiating corners at opposite ends of the geopolitical football field from which there was no easy rhetorical escape and no middle ground.

“Alan Gross’s release…”?

I couldn’t turn my phone back on. I had to concentrate on the meeting; I’d agreed to serve as official note taker. Finally, we confirmed the date of our next meeting, and wished each other happy holidays.

I immediately turned on my phone and called my wife. Jeanie would know what was happening. “They’re free,” she said without preamble, but with what sounded like this-can’t-be-happening disbelief. “They’re home in Havana! All of them! And there’s more…” I could tell she’d been crying. And I realized I was too.

This was… strange. Very strange. Five years before, I didn’t know who the Cuban Five were, and now I was weeping at news three of them — none of whom I had met face to face — had been released and returned to their families in Cuba.

I’m not a weeper. I’m a journalist. I’ve written books about traumatic events. I’ve interviewed women who told me wrenching stories of sexual assaults they said they’d endured at the hands of a former premier of Nova Scotia. I’ve led a mother, whose teenaged daughter died in an airplane crash, through the minefield of memories about her own occasionally fraught relationship with her daughter. Each of those stories affected me profoundly. But they didn’t make me cry.

And yet here I was, alone in my office in the basement of the university, my door shut, holding the phone to my ear, staring out the window at a rain-snow mix pelting the cars in the parking lot, and crying.

***

It’s complicated. Soon after the release of my previous book, my wife had suggested, ever so gently, I broaden my topical and geographic literary horizons. So I decided to set my next book, a novel, partly in Cuba.

Cuba? I’d like to tell you it had something to do with the historic Nova Scotia-Cuba connection that stretches back beyond Prohibition days when Nova Scotia was a popular trans-shipment point for Cuban rum, but I’d be lying. Where would you rather research: tropical Havana or wintry Halifax?

So in the spring of 2009, I flew to Havana, hired a local guide to show me the city tourists never see. One evening, sitting on the terrace of Havana’s famed Hotel Nacional overlooking the Bay of Havana, smoking cigars and drinking mojitos, our conversation meandered into U.S.-Cuban relations. Would those improve, I wondered naively, with Barack Obama — a Democrat, a liberal, an African American — in the White House?

“Nothing will change between Cuba and the United States,” he said flatly, “until they solve the issue of the Cuban Five.”

The Cuban who…?

After I returned home, I searched online for a 2005 Fidel Castro speech he’d recommended. “It’s all there,” he told me. “Names, dates, places.” By the time I’d read its entire 10,286 words, I realized this was a far more intriguing story than any I could dream up.

That didn’t mean I was a true believer. In the beginning I was less concerned about who was telling what truth, and much more about the narrative possibilities offered up by a bunch of Cuban spies infiltrating exile terrorist groups while being followed by scores of FBI agents in exotic locales against the geopolitical backdrop-brew of post-Cold War politics. With cameo appearances by Fidel Castro, Bill Clinton, and even Nobel-prize-winning Colombian novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez who’d carried a secret message from Castro to Clinton in the spring of 1998.

It wasn’t until I eventually tracked down a copy of the more than 20,000-page transcript of their seven-month trial that I began to understand this was much more than a spy caper gone wrong.

The prosecution evidence, particularly on the most serious counts, ranged from flimsy (conspiracy to commit espionage) to non-existent (conspiracy to commit murder). The Five had been convicted largely because they’d been tried in Miami.

Worse, while the U.S. government had become eager after 9/11 to divide the world into those who supported its “war on terror” and those who coddled terrorists, America’s dirty little secret was that it had coddled many. It had trained, encouraged, harboured, then looked the other way while literally dozens of Florida-based exile groups carried out hundreds of terrorist attacks against Cuba, including blowing up an airplane, killing all 73 aboard, in 1976, and setting off a string of bombs at tourist hotels in 1997, killing an Italian-Canadian businessman and injuring scores of others.

The mastermind of both those attacks, Luis Posada Carriles, is still alive and living in Miami — not just a free man but a respected, celebrated elder statesman of Miami’s Cuban-American community.

Given the FBI’s conscious failure to pursue anti-Castro terrorists, Cuba had sent its own agents to Florida to infiltrate their organizations, uncover their plots and report back to Havana so authorities there could arrest them before they did their worst.

So this wasn’t just a spy thriller. It was a true story about a shocking miscarriage of justice, and a tale of high-level government hypocrisy. How could I not be hooked?

The publishing world was not. My agent, who’d sold my previous book ideas to major Canadian publishers, couldn’t interest any of them in this project. American publishers surprisingly — to me — were even less interested. I wasn’t deterred. For reasons I can’t explain, even to myself, I became obsessed with the story, continuing to work on it without the prospect anyone would publish it.

Someone did, eventually. Fernwood, the progressive Canadian publisher that happens to be based in Black Point, N.S., and had coincidentally published a number of important Cuba-related titles over the years, thankfully agreed to publish What Lies Across the Water: The Real Story of the Cuban Five.

By the time it was published in the summer of 2013, I’d already contacted authors of actual books about Cuba, as well as public intellectuals like Noam Chomsky and celebrities like actor-activist Danny Glover. I offered to send them copies of my manuscript. After they’d (hopefully) read it, perhaps they might — please! — write a short blurb I could feature on the back cover.

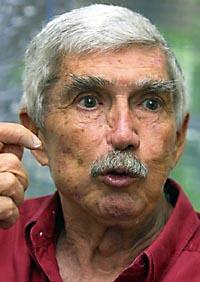

Wayne Smith was one of those I wrote to. Smith had been a young foreign service worker at the American Embassy in Havana when Fidel Castro’s revolutionaries swept into power in 1959, and was among those forced to flee when the embassy shut down in 1961. He’d returned to Havana in 1979 as the chief of mission at the U.S. Interests Section, but left shortly after Ronald Reagan took charge in 1980, and was now a respected critic of America’s Cuba policy.

Smith was quick to respond to my request. “Received your book today and will start reading tonight,” he emailed on October 24, 2011. The next day, he emailed again: “I’m about half way through… This is, without question, the best and most authoritative report yet on the Cuban Five. Should I just send a couple of paragraphs to you saying that or, better, to the publisher, or what?”

Uh… yes, please, and thank you!

Two months later, he invited me to speak at a conference he was organizing in Washington. It happened Alicia Jrapko, the leader of one of the main American groups lobbying for the freedom of the Five, was planning her own event — tentatively titled “5 Days for the Cuban 5”— in Washington in April 2012, and had asked me to participate. Perhaps, I suggested, she could coordinate with Wayne.

In April 2012, my wife and I flew to Washington for Wayne’s conference and Alicia’s 5 Days. Since I still didn’t have a book to sell, I brought copies of a postcard announcing its… forthcoming release.

***

For more than 20 years, Jeanie and I had operated on never-the-twain-shall-meet work schedules. I taught at the university from September to April. Just as my classes wound down, Jeanie’s projects — she was a costume designer for American and Canadian film and television — ramped up. Her 12-14-hour-a-day shooting schedules usually stretched from early spring until late November. By then, of course, I was teaching again. So we rarely vacationed together.

The year before, however, Jeanie had decided to retire from that all-consuming world and start her own, more predictably paced wardrobe consulting business (Style-Me! A Kinder, Gentler What Not to Wear). We decided to turn my Washington speaking engagement into a combined business-vacation-adventure. Although born and raised in New York, Jeanie had moved to Canada soon after we met in the mid-1970s. The last time she’d been in Washington was in November 1969 when she was among the more than 500,000 who converged on the capital to protest the Vietnam War. We decided we’d see some sites, visit the Holocaust museum, maybe the Newseum…

On our first night in Washington, we attended a pre-5 Days reception at the Cuban Interests Section. While I sampled the mojitos and made small talk with Wayne, Jeanie struck up a conversation with two women from Alicia’s International Committee who were organizing the next day’s lobbying at the U.S. Congress.

“Why don’t you join us?” they suggested.

Why not? And that was how that began. Jeanie would eventually become a member of the sub-committee organizing lobbying visits, and later its coordinator. And we would both join the International Committee. Another giant, scary leap for a life-long, non-joiner journalist.

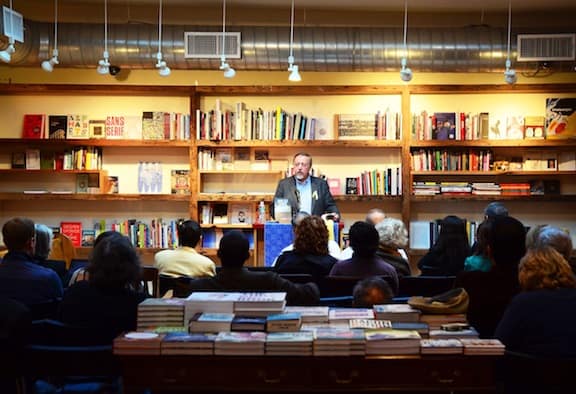

When What Lies finally did come out, Alicia and her partner, Bill Hackwell, a social documentary photographer and activist, organized a book tour of the American northeast. We traveled by car caravan from Washington to New York and Boston, staging a whirlwind of readings and events in each city, including one at MIT with Noam Chomsky. Later, Jeanie and I flew to California where Bill and Alicia organized another book tour in their home state. Other groups from all over North America invited me to speak about the case. I earned my frequent flyer points that year.

***

Still, it did find a significant audience among key American policymakers and — I like to imagine — played some very modest role in the wonderful way the story ultimately turned out.

Famed New York first amendment lawyer Martin Garbus cited my soon-to-be-published book’s revelations at length in a 2012 affidavit to set aside the conviction of Gerardo Hernandez — the agent sentenced to double-life-plus-fifteen-years — on the basis of new evidence.

Tim Rieser, the chief advisor to Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy, one of the key political figures pressuring the White House to consider a prisoner swap, circulated copies of the book to influential contacts in the State and Justice Departments, as well the White House, as part of his effort to convince them to examine the actual evidence in the case.

In June 2014, I was part of an International Committee delegation that met twice with senior State Department Cuba officials. It was the first time the department had agreed to meet. After, I gave Ray McGrath, the State’s Department’s coordinator of Cuban affairs, and Alex Lee, the deputy assistant secretary for South America and Cuba, copies of the book. As we were leaving, McGrath confided: “My wife wants to read your book first. Maybe I’ll read it after her.” I wasn’t sure if he was joking.

Intriguingly, even Scott Gilbert, the lawyer for Alan Gross, the American USAID contractor imprisoned in Cuba, encouraged administration officials to read my book, which he told me later was “very helpful [in] setting the stage. The initial reaction [from] folks in the administration was, ‘[the Cuban Five are] a bunch of terrorists…’ The book really provided a terrific backdrop to be able to sit down and say, ‘Actually, let me tell you what these people were doing here, let me put this in context for you,’ and that was very significant.”

Without an agreement to release the Five, Gilbert already knew, there could be no deal to free his own client.

In April 2014, Attorney General Eric Holder reversed the longstanding American presumption the Five had gotten a fair trial and reasonable sentences, and agreed to recommend commutation of the rest of the sentences of the three still in jail.

That became the magic key to unlock more than 55 years of poisoned US-Cuba relations and lead to what President Barack Obama, in his December 17, 2014, announcement, called “the most significant changes in our [Cuba] policy in more than fifty years.”

***

Havana, Cuba

May 3, 2015

Jeanie and I had spent a spectacular spring week in Cuba with American members of the International Committee to Free the 5, not only celebrating the success of the campaign to free them but also enjoying attractions I’d missed on my previous research-and-interview-obsessed visits.

Thanks to organizers at ICAP (the Cuban Institute for Friendship with the Peoples), we got to tour La Escuela Taller Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, a school in Old Havana that trains 18-21-year-old Cubans in the craft and art of restoration bricklaying, carpentry, painting, stonemasonry, smithery, plumbing, even gardening, so they can rescue and rehabilitate Havana’s historic but crumbling city centre. We visited Fábrica de Arte Cubano (FAC), an eclectic, avant-garde art gallery/performance space/nightclub — “Studio 54 meets Warhol’s Art Factory,” said one critic — in a converted olive oil factory in Vedado. We ventured into Havana’s suburbs to “Fusterlandia, the studio, residence and wild kingdom” of famous Cuban artist José Fuster, the “Picasso of the Caribbean.” We even traveled to Santa Clara to visit the world-famous Che Guevara Mausoleum. And we spent May Day 2015 in Revolution Square with a million or so of our closest Cuban friends celebrating the return of the Cuban Five.

In between, we hung out with Gerardo, René, Ramon, Tony and Fernando, five “brothers” united again after years locked up in separate prisons spread across the United States. We spent time with them and their families in small, intimate gatherings, at parties, at official and unofficial events.

We also got to see how ordinary Cubans responded to them. When I began researching the story, Americans insisted Cuban support for the Five was just government propaganda; if 100,000 people marched, it was only because Fidel made them do it. But it would have been hard to fake the night in the bar at the Havana Libre hotel when literally dozens of employees spontaneously descended on our table — the band even stopped playing and lined up — to get an autograph, or have their picture taken with Gerardo. And then there was the little old lady who came up to René on the street one day, with tears in her eyes. “Gracias,” was all she said.

There is no question the Five will play significant roles in an evolving, changing-but-unchanging Cuba. The BBC is not alone in suggesting Gerardo Hernandez may one day be president.

On May 3, we attended a farewell dinner with all of them at a restaurant in Vedado. Jeanie and I were about to depart for a week at a beach resort; they were headed to Venezuela, a first stop on what has become a year-long global tour to thank those who’d supported their cause during their years in prison.

“Kimber?” The cheerful voice belonged to René, the oldest of the Five. We’d begun a prison correspondence in May 2010. Through my endless questions and his patient answers, we’d become friends. These days, we shared the global bond of grandfather-hood. “Do we have a picture of you with the Five?” he asked.

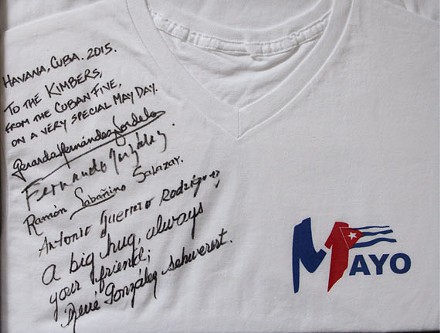

We didn’t. We rectified that. Then someone produced white May Day t-shirts. Gerardo wrote an inscription on the front of one:

Each of them signed, and presented it to Jeanie and me.

I felt the tears well up. Again.

***

Halifax

December 2015

These days, I like to tell people I’m in my “Cuban-ist” period. There’s now a German-language edition of the book. Jeanie and I will be in Havana in February for a launch of the Spanish-language edition at the Havana International Book Fair.

My next book-in-progress is Cuba-related too. It’s about those 18 months of secret negotiations in Ottawa and Rome between lips-sealed Cuban and American negotiators — the ones featuring an Alan Gross-suicide watch, an unrelated prisoner swap that complicated everything, a pilot-less plane that almost inadvertently crashed hope for any deal, the divine intervention of the pope and even a long-distance pregnancy that had to be hidden from the world — all leading to last December 17th’s dramatic prisoner swap and historic rapprochement between the United States and Cuba.

I’m also working with Barrie Dunn — one of the producers of the original Trailer Park Boys series — on a feature film about the Cuban Five based on the book. We’ve traveled to Cuba several times during the summer and fall to meet with the Five and with Cuban film production officials about what we hope will be a soon-to-be-a-major-motion-picture Cuba-Canada co-production.

Like me, like Fernwood, Barrie has become yet another unlikely, accidental Nova Scotia-Cuba connection to this story. Back before there was a manuscript, Barrie had stumbled onto my website looking for something else, discovered my ethereal Cuban book-to-be and became hooked on its dramatic possibilities.

Welcome to the club.

This story was originally published in The Coast, December 10, 2015.

—

What Lies Across the Water: The Real Story of the Cuban Five is available as an ebook from the website for $9.99. You can also purchase the trade paperback edition from Amazon or directly from the publisher.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

lying commie pig