From What Lies Across the Water: The Real Story of the Cuban Five by Stephen Kimber. Published by Fernwood Publishing, 2013.

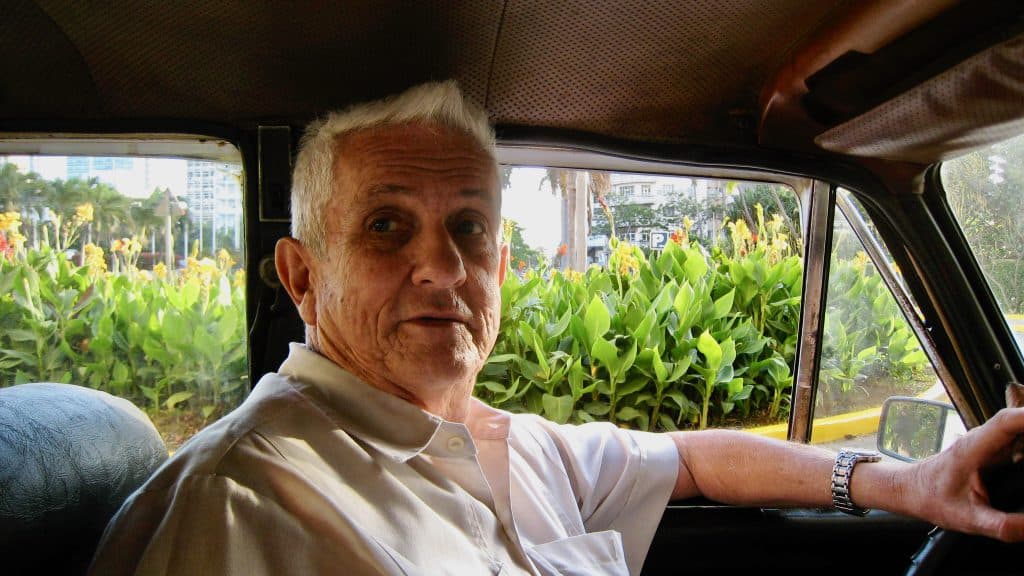

This is both a tribute and a thank you to Alejandro Trelles, the Cuban guide who introduced me to the story of the Cuban Five. I will be forever grateful. Alejandro died on August 19, 2022.

***

This is not the book I intended to write. That book was to be a novel, a love story set partly in Cuba. In the spring of 2009, I traveled to Havana to do some preliminary research for it, and got sideswiped by the truth-is-stranger-but-way-more-interesting nonfiction story of the Cuban Five.

I’d vaguely heard of them. Back in 2004, my wife and I spent a week at Breezes Jibacoa, a beach resort halfway between Havana and Varadero. It was there, in fact, that I conceived the idea for the novel, perhaps for no better reason than to ensure I would have to return.

Like most Cuban resorts at the time, communication with the outside world from Jibacoa was primitive: two painfully slow Internet-connected computers tucked away in a second-floor lounge. Since you invariably had to line up to use them, I filled up my waiting time one day literally reading the writing on the wall—a collection of Soviet-style government posters about the plight of a group of men known as the “Cuban Five.” They were, the posters declared, “political prisoners” in the United States. The English translation was awful — “Prisoners of the Impire” was the heading on one — and the information about their case was confusing and frustratingly incomplete.

As if I should already know the details.

I hadn’t a clue.

When I returned to Canada, I did a Google News search for “Cuban Five” but found only one mainstream American news story from the previous month—in spite of the fact lawyers for the Five were in the midst of appealing their controversial convictions up the ladder of the U.S. court system. Most of the rest of what I discovered about them on the Internet consisted of polemics, which painted the Five in virginal white or blacker than black, either as heroic young patriots worthy of veneration or as murderous villains for whom even the death penalty wasn’t punishment enough.

Reading between the bombast and broadsides, the short version seemed to be that the Five were members of a Cuban intelligence network who’d surreptitiously entered the United States, infiltrated various militant anti-Castro groups, got caught by the FBI, were tried and sentenced to lengthy prison terms.

I wrote a brief newspaper column about what I’d learned—and the fact no one except the Cuban government seemed to care—filed it and forgot it.

Until five years later, that is, when I met Alejandro Trelles Shaw.

Alex was an energetic 70-year-old Cuban who could still vividly remember what it had been like to be an idealistic 20-year-old banker caught up in the headiest days of the life-altering Cuban revolution. Unlike the rest of his well-to-do family, who all fled to Miami or ended up in jail after Castro took power, Alex stayed. “I was the red sheep of the family,” he jokes. “I looked around, saw what the revolution was trying to do. I thought, ‘if this is communism, then I’m a communist.’”

He eventually became a counter-intelligence officer in Cuba’s Ministry of the Interior (MININT), the all-powerful ministry responsible for foreign and domestic intelligence, among many other duties. Alex can—and will if you ask—regale you with fascinating tales of how he infiltrated CIA-backed student groups at the University of Havana, and later served as a government “minder” for various Cuban sports teams and delegations when they visited other countries. Without seeming to brag, he would explain he’d also occasionally translated for the “Commander” when Castro traveled abroad.

Not that he ever totally swallowed the Kool Aid. “Part of the problem in Cuba,” he told me, “is that Fidel was involved in everything. I call it the Law of the Jeep. Fidel would arrive in his Jeep, he would talk and then he would leave, and suddenly we had a new law.”

When he was in his late fifties—for reasons I’m not sure I understood or that mattered all that much—Alex had a falling out with his bosses, and retired. In the mid-1990s, he got kicked out of the Communist Party but somehow managed to hold onto his prized party ID card.

Like plenty of others in that distressed, depressed, post-Soviet, “Special-Period-in-Time-of-Peace” Cuba, Alex re-invented himself. He became a grey-market entrepreneur, employing his language skills, guile and charm to survive in impossibly difficult circumstances. One of the many services he offered was as a guide and raconteur for tourists who wanted a “no-guff introduction to the real Havana.”

I did. I’d read about him in a newspaper travel story before I left home, and I gave him a call soon after I arrived in Havana in May 2009.

He picked me up at my hotel the next morning in his battered, Russian-made Lada. He’d been allowed to buy the car back in 1979, he told me, as a reward for being a good communist. The price: 2,200 pesos, paid off at 35 pesos a month for five years, interest-free. The engine now had over 400,000 km on it and was, he claimed, running just fine.

We spent the day tooling around parts of the city I’d never have experienced on my own. But far more interesting than what I got to see—as interesting as that was—was getting the chance to listen to Alex’s stories: in the car, over cigars after lunch at an outdoor restaurant where everyone knew his name, over drinks back on the terrace at the Hotel Nacional where the security guards kept an especially watchful, wary eye on a smooth-talking Cuban in relaxed English conversation with a foreigner.

He’d been married three times, he told me, had four children and four grand-children. These days, he lived in a one-bedroom apartment with his 18-year-old daughter, a university student. She slept in a second bedroom he’d carved out of the balcony. To save money, he never turned on the air conditioning. But he had an antenna on the roof of his building so he could watch television. And he had an Internet connection, in the name of a friend.

Alex was interested in, and thoughtful about, the world beyond Cuba. Because many of his customers came from Canada, he told me, he read the Globe and Mail online every day. He mentioned a recent report in that paper about a speech Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega had given at the Summit of the Americas. “When you only get one side of the story,” he asked, referring more to me than himself, “how can you be informed?”

He even followed Canadian politics. “What do you think of Stephen Harper?” he asked at one point.

I was curious too. Barak Obama had just won the American presidency and there was much wishful hoping among my liberal friends in the United States that his ascendancy might finally signal not only an overdue end to the counter-productive U.S. trade embargo but also fresh water in the poisoned well of personal relations between the two old enemies.

What did Alex think Obama’s victory might mean, I asked, assuming the best?

He paused, took a contemplative puff on his cigar, exhaled. “Nothing,” he said simply. “It doesn’t matter who is the president of the United States or who is in charge in Cuba. Nothing will change between Cuba and the United States until they resolve the issue of the Five.”

The Five?

Suddenly, I was back to the Cuban Five.

In Cuba—as I was about to discover—all conversations about the future of Cuba-U.S. Relations invariably wind their way back to Los Cinco.

In Cuba, their real-life story has long since transcended mere fact to become myth. Hundreds of thousands of Cubans have marched past the United States Interest Section in Havana shouting demands for their release. Their images are ubiquitous. They stare back at you from highway billboards beneath a starkly confident—or perhaps just hopeful—message: “Volverán.” They Will Return. Much younger versions of their faces are painted on fences, the sides of apartment buildings, office waiting-room walls, postage stamps, even on stickers glued to the dashboards in many of Old Havana’s Coco cabs.

Though they still rank below Fidel and Ché in the revolutionary pantheon, they have become certified, certifiable, first-name Heroes of the Revolution. Ask any Cuban school child and they can rhyme off those first names: Gerardo, René, Antonio, Ramon and Fernando. The children will inform you that los muchachos—all are now well into middle age, but are usually still described in Cuban propaganda as “the young men”—are Cuban heroes unjustly imprisoned in the United States for trying to protect their homeland from terrorist attack.

The Cuban version of their story is straightforward: During the nineties, Miami-based counter-revolutionary terrorist groups were plotting—and sometimes succeeding in carrying out—violent attacks against Cuba. Since the American government seemed unable or unwilling (or both) to stop them, Cuba dispatched intelligence agents to Miami to infiltrate these violent anti-Castro organizations, find out what they were planning and, if possible, stop them before they could wreak their havoc.

Sometimes they succeeded, sometimes they didn’t. An Italian-Canadian businessman was killed in one 1997 explosion at a Havana hotel.

To prevent an even worse tragedy, Cuba reluctantly agreed to share the fruits of their agents’ work at an unprecedented meeting between Cuban State Security and the FBI in Havana in June of 1998.

But the FBI, instead of charging the terrorists the Cubans had fingered, arrested Cuba’s agents instead.

The Five were thrown into solitary confinement for close to a year and a half to break their will, then tried in a rabidly anti-Castro Miami, convicted and sentenced to unconscionable prison terms ranging from 15 years to something obscenely described as double life plus 15 years.

For what? For trying to prevent terrorists from attacking their homeland. Surely, in the wake of 9/11, Americans could understand the necessity of the kind of heroic work the Five had been doing…

***

I will confess that—on that hot spring afternoon when Alex Trelles and I were sitting on the terrace at the Hotel Nacional contemplating the view of the sparkling waters of la Bahia de la Habana, sipping mojitos, puffing cigars and discussing the future of Cuban-American relations in the Obama era—I understood almost nothing about the unfathomable pit of this abyss between American and Cuban versions of reality when it came to… well, everything .

But I knew I was intrigued.

Was any of this documented, I asked?

“Fidel gave a speech,” he said. “It’s all there. Names, dates, places. They put it on the Internet. In English. Look it up.”

Eventually, I did. The speech, which was delivered on May 20, 2005 at the José Marti Anti-imperialist Square in Havana, opens with a kind of breathless urgency. “My fellow countrymen,” Castro begins, “what I will immediately read to you has been elaborated on the basis of numerous documents from our archives. I have had very little time, but many comrades have cooperated…”

It was hardly a speech in the way I understood speeches, even speeches by a legendary speechmaker like Fidel Castro. It was, essentially, a remarkable 10,286-word oration in which the Cuban leader read into the public record details of every one of the significant events of the 1997 Havana hotel bombing campaign: from April 12, 1997 (“a bomb explodes in the ‘Ache’ discotheque at the Melia Cohiba hotel”) to September 12, 1998 (“the five comrades, now heroes of the Republic of Cuba, are arrested”).

“It’s all there,” Alex repeated. “Even the part about García Marquez.”

Gabriel García Marquez? The Nobel prize-winning Colombian novelist?

In the middle of the bombing campaign, it turned out, Castro had asked his good friend García Marquez to carry a top secret message about the Miami exiles’ latest, even-worse-than-bombing-hotels terrorist plot to Washington. As Castro explained in his speech: “Knowing that writer Gabriel García Márquez would be traveling to the United States soon where he would be meeting with William Clinton, a reader and admirer of his books (as so many other people in the world)… I decided to send a message to the U.S. president, which I personally drafted.”

…

“After you read that speech,” Alex told me that afternoon, “you’ll begin to understand why the Five matter so much here and why nothing can really be resolved between Havana and Washington until they are returned to Cuba.” He paused, smiled. “But you’ll only begin to understand… It’s complicated.”

It was. It is…

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books