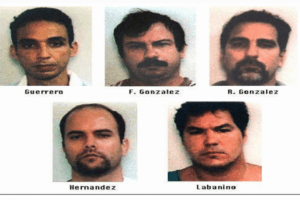

In the weeks following their arrests in September 1998, Gerardo Hernandez, René González, Ramon Labañino, Fernando González and Tony Guerrero — the Cuban Five — were as alone as they would ever be. They were being held in solitary confinement in the Miami Detention Center. Five of the comrades arrested with them were in the process of negotiating plea deals and agreeing to testify against them.

The Five themselves, however, well understood the code of their clandestine intelligence agent profession. It directed them to admit nothing, to stick to their cover stories no matter the FBI threats or inducements. So they did.

But, at the same time, they were well aware the Cuban government had officially disavowed them. It claimed to know nothing about them, or what they were doing in the United States, other than what it had read in American news wire reports.

Which meant Cuban consular officials in Washington could have no contact with them. They couldn’t contact their own families back in Cuba either. And they couldn’t even admit who they really were to their court-appointed American lawyers, those who were supposed to defend them against espionage charges.

They needed a message, some sign from Havana, about what to do next.

That message came — incredibly, circuitously, serendipitously — from Fidel Castro, the then-Cuban president, who is about to celebrate his 90th birthday August 13, 2016.

What follows is the story of the first difficult weeks the Five spent in jail in Miami, and the unlikely courier who conveyed Fidel’s message to them.

***

“Hey Cuba!” It was the guy in the cell across the corridor. “Hey Cuba!” he shouted again, trying to get his attention.

Gerardo Hernandez

Gerardo Hernandez knew him as “the cocaine cowboy guy,” though he was no drug dealer. His name was Miguel Moya, and he’d been the jury foreman in an infamous 1996 Miami trial involving two reputed drug kingpins charged with smuggling seventy-five tons of cocaine from Colombia into the United States. Despite what prosecutors considered a slam-dunk case, the jury acquitted the men.

But then, after a two-year investigation into Moya’s lavish post-acquittal lifestyle — he bought himself a house, a boat, a Cadillac, and a Rolex watch, among other extravagances — prosecutors charged him with accepting at least $500,000 in cash payoffs from the drug gang to fix the trial’s outcome. Which is why Moya was now in the cell across from Gerardo, awaiting his own day in court. They’d become jailhouse acquaintances, in part, because Moya’s lawyer, Paul McKenna, was also Gerardo’s lawyer, and because Moya would be appearing before Judge Joan Lenard, the same judge handling the case against the Five.

Foto©Rene Perez Massola

It was October 21, 1998, their thirty-ninth day in custody. Not that there was much to distinguish one day from another, not when you spent twenty-three of every twenty-four hours alone inside an eleven-by-seven-foot concrete-and-steel box — a space not much larger than a king-sized bed — where you ate, slept, urinated, defecated, showered, shaved, read, wrote, thought, and tried not to think too much.

The box came complete with an iron double bunk bed, a small triangular table built into one corner with a tree-stump-shaped concrete stool beneath, and a stainless steel combination toilet-washbasin in an open stall that also served as your shower. Meals were delivered on trays slid through a slot in the steel cell door.

Gerardo approached the door to see what Moya wanted.

“Hey Cuba,” Moya called again, this time waving a copy of today’s Miami Herald across his own window. “Your boss is talking about you.”

Now he had Gerardo’s full attention. Could this be the “message” he’d been hoping for?

***

Miami Federal Detention Center

Three weeks before, on September 29, 1998, Gerardo and the seven other male Cubans — including, incredibly, those negotiating plea deals — had been transferred from the thirteenth floor to the twelfth, to the Special Housing Unit, or SHU, official names for solitary, or segregation, or the hole. The SHU in the Miami Federal Detention Center consisted of two wings of with thirty cells each, connected by a small recreation area. Most cells were designed to hold two inmates, but someone had determined the Cubans should be kept apart from other inmates, and separate from one another (though they were usually placed in contiguous cells). In addition to Moya, their SHU-mates ranged from the dangerous (six members of the “Moscow Posse,” a violent Jamaican drug gang, who were awaiting trial for murdering would-be rivals and had recently caused “a riot in the court room”) to the deranged (“a crazy Cuban man named Castro” who ate newspapers and magazines, didn’t sleep at night and would spend his time banging on the upper bunk with his feet, or painting his cell walls with his own feces, or stuffing the toilet so it would overflow into the rest of the unit).

Being in the SHU made everything more difficult, including meeting with their lawyers. Instead of the typical half-hour wait to see his client, a lawyer meeting a SHU inmate might have to cool his heels for an hour and a half or longer until someone found a vacant room on the twelfth floor for them to meet. Often, the lawyer and client would be separated from each other by a thick sheet of plexiglass. They’d have to yell just to be heard and, if the lawyer wanted his client to read a document, he would have to hold it up to the glass and turn it, page by page. Not that that mattered all that much in this case, since the Cubans were still refusing to cooperate with their lawyers, or even — in the case of the three using fake IDs — admit they were not Mexican or Puerto Rican.

The Five had been following their agent playbook — don’t acknowledge, don’t co-operate — while they waited for some sort of new message from Havana that would tell them how they should proceed. But getting a message through to them would not be easy. Inmates were only permitted non-lawyer visits one day a week for one hour, and you had to be on a vetted list to get to see them. That was not an issue for Gerardo, Ramon, or Fernando, of course, who had no one to visit the persons their fake identities said they were. Tony tried to contact family members in Miami, but someone had already called their house and threatened them for their connection to the Cuban “spy,” so they wanted nothing more to do with him. Tony’s girlfriend, Maggie, who lived three hours away in Key West, did visit whenever she could, and brought him books, including one by a Buddhist teacher he and Maggie had seen earlier that year. She also put money in their commissary accounts so they could buy supplies and get a radio. René’s wife Olga came every week, and would occasionally attempt to smuggle in pens — which were in short supply in the SHU — in her bra. Once, a pen triggered the metal detector, and she had to retreat to the bathroom to get rid of it.

The hardest part about their days in the SHU was keeping their minds and bodies engaged.

***

One of the few places where they could talk with some hope of privacy was in the recreation area. Sandwiched between the two wings of solitary confinement cells, it consisted of a six-by-six meter space, closed in by concrete walls on three sides. The fourth wall, facing the street, was constructed of thick, opaque glass blocks that allowed some light in, but blocked the inmates from seeing out. A ventilation grid at the top of the outside wall allowed a little outside air to circulate. There was no furniture, just a metal rail along the exterior wall where inmates could try to sit. Prisoners were officially allowed one hour of recreation each weekday, usually early in the morning.

Whenever there was an issue the Five needed to discuss, they would agree to all ask for recreation time the next day. But there was no guarantee they would get to go together. It depended on how many other inmates had asked that day, and, often, on the mood of the guards. Because they were being kept away from other inmates, the Cubans never had to share their recreation space with others — except, early on, with some of the men who had already made deals! After a while, the guards separated the two groups, so they were not in the recreation yard at the same time. That didn’t stop them from attempting to communicate with each other.

One morning, Nilo Hernandez, one of those copping a deal, left a note — Of explanation? Apology? Defiance? — in pencil on one of the walls.

“Before I used to fight for my homeland,” he declared. “Now I fight for my children and for my family.”

The next day, Gerardo smuggled his own pencil into the rec area and wrote a response beside the first: “I’ll keep fighting for our homeland, for my family, and for your family.”

Fighting for our homeland…

That’s what the Five were trying to do now. Following the standing orders in their agent playbooks. But were those still the orders? And how would they know if the orders changed.

Their silence that had created its own complications — and endless questions, including for them. What about their families back in Cuba? Had their families been told they’d been arrested? If so, how much had they been told about their mission in the United States — and how had their families reacted to the news they’d been deceived for years by fathers, sons, husbands, brothers? Did they understand? Were they angry? Hurt? In jail in Miami, the Five couldn’t know, because they had no way to communicate with them.3

And then there was the question of the mission itself. How had their bosses in Havana reacted to news their network had been broken? Should they continue to cling to identities and cover stories they already knew the FBI knew were false? Or should they…?

“Hey Cuba.” It was Moya again, waving the newspaper. “Wanna see?”

Gerardo did. So Moya attached his copy of the newspaper to a length of string torn from his mattress. The other end of the string — the line — was attached to “a car,” an empty toothpaste tube with batteries inside for ballast. Moya expertly skimmed the car under his own cell door and across the floor to Gerardo’s cell, so Gerardo could reel in his catch. During their short time in the SHU, Gerardo and the others had already learned much about the ingenious ways in which inmates communicate with each other, including using this “car and line” system to share magazines, notes and anything else that fit under a cell door. Gerardo, in fact, had spent hours perfecting his own throwing technique so his car would sail under the door with just enough force to reach its intended target in another cell.

Now he opened the newspaper Moya had sent him, found the article about his “boss.” It began predictably with news Gerardo already knew but didn’t want to acknowledge: “On the eve of two more guilty pleas in South Florida’s celebrated Cuban spy case…”4 but went on to quote his “comandante.” During an interview with CNN Havana bureau chief Lucia Newman at the Ibero-American Summit in Portugal that week, “Fidel Castro confirmed that he sometimes sends spies to the United States. But Castro said his targets are Cuban exile groups — not military bases — and accused the United States of tolerating U.S.-launched terror attacks against his island.”

There was, of course, an immediate, next-paragraph denial by the State Department — “spokesman James Rubin dismissed Castro’s allegations as ‘ridiculous,’ saying the United States does not sanction anti-Havana terror tactics” — but there was more, and more interesting information buried deeper in the story.

Toward the end her interview with Castro, Newman had noted that ten Cubans had recently been arrested in Florida “on charges of spying for your government. What can you tell me about that?”

“The first thing that attracted my attention,” Castro parried lightly, “was how amazing it was that the country that does the most spying in the world was making spying charges against the most spied-on country in the world.”

But in his more detailed answer, Castro also sent what appeared — to Gerardo at least — to be a coded message aimed directly at the men in jail. “If we knew something” about the case, Castro told Newman, “it would be disloyal to report it. If anything exists, let those accusing them prove it. They can not count on any cooperation from us for that.”

And then he added: “If any of the people in that ring has acted to try to obtain information for Cuba — the information that we are essentially interested in, the only information of interest to us, information on the acts of terrorism organized in the United States against Cuba — we will support them whatever they say and whatever they do.”

This was the message he’d been waiting for! Their comandante — their country — was behind them. “That was decisive for us,” Gerardo says now of Castro’s reassurance. “From then onward, the enemy had no chance with us.”

Gerardo used his car-and-line skills to send the newspaper to Ramon in the next cell, who read it and passed it on to… They agreed to all ask for time in the recreation area the next morning. “We convened our own Mesa Redonada (Roundtable),” Gerardo joked, referring to a popular Cuban TV news program.

But was this really the “green light”? Castro said he would support them in whatever they said and whatever they did. But what should they say, and do?

***

Stephen Kimber, the author of What Lies Across the Water: The Real Story of the Cuban Five, is currently researching a new book on the secret negotiations that led to the December 17, 2014 announcements by Cuban President Fidel Castro and U.S. President Barack Obama, that the two countries were normalizing diplomatic relations after fifty years of hostility.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books