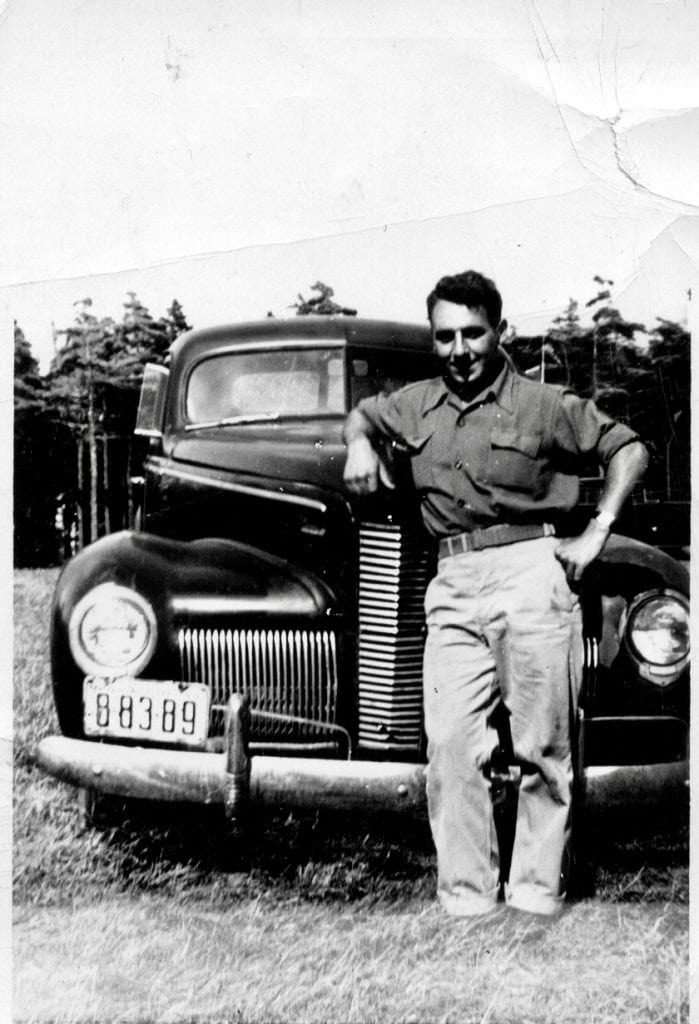

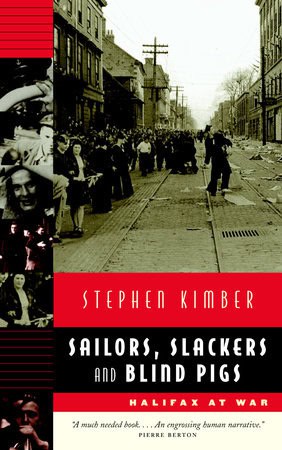

Bill Mont, who died on October 28, 2025, at the age of 96, was one of Halifax’s legendary characters. He would become best known as Nova Scotia’s “Flea Market King” during the 1970s and 1980s. But he was also one of the “characters” who helped me bring to life everyday life in Halifax during World War II in my 2003 book, Sailors, Slackers and Blind Pigs: Halifax at War. The following excerpts from Sailors, Slackers, cover Bill’s hardscrabble growing-up years from 1939 to 1945, and are based on my interviews with him.

“Bend over, Mont.” The deep voice boomed off the bare walls of the cavernous room, making it seem to 10-year-old Billy Mont even louder and more ominous than it might actually have been. “And get those pants down. Now!”

The Gad! He was going to get the Gad! That’s what he’d heard the other boys call the wide leather strap authorities at the Halifax Industrial School used to discipline the boys. He didn’t know why they called it that. Billy had never been strapped before. Now he was about to feel the bite of the leather on his backside too. And for what? For flushing the toilet. How was he supposed to know it would overflow?

At home in Greenbank, there had been no flush toilets, only an outdoor privy. The water didn’t come out of a tap either. When Billy’s family needed water, his grandfather would send him down Clarence Street to the Young Avenue bridge, where a spring bubbled up from under the ground. As he filled his bucket, Billy could look up and see the mansions on Young Avenue where the rich folks lived. There was a real castle up there. He’d seen it with his own eyes.

There were no castles in Greenbank. Greenbank was a shantytown, a jumble of shacks hastily slapped together to house the hundreds of workers brought in to build a harbourside complex of modern piers and sheds in the late twenties. The shacks were supposed to have been torn down after the terminals opened, but they survived. Families took them over and added on. Other folks built new cottages nearby. Some of the land those cottages squatted on was bought up by the local gentry who regarded the strategically situated shantytown, just west of the CNR train station and the new international Ocean Terminals complex, as a wise, long-term investment. Billy’s grandfather paid five dollars a month for their two-bedroom cottage, which had no running water, sewage or other city services, to Susan Mack, the widow of a prominent Halifax doctor.

During the thirties, Greenbank had become a grudgingly accepted Halifax address. Accepted by some, but certainly not by its closest neighbours. The problem was that Greenbank sat rudely, inconveniently, incongruously smack in the middle of Halifax’s most exclusive streetscape.

By 1939, Halifax’s lines of social demarcation were immutable : the northeast quarter of the peninsula belonged to the poor and working classes, with Africville — a poorest-of-the-poor segregated community of about 400 that was the black equivalent of Greenbank — anchoring the farthest north end where the harbour met Bedford Basin. The gentry, which had originally favoured the downtown core for homes as well as businesses, had long since abandoned it to commerce and the dregs of the waterfront, developing their own deliberately closed residential neighbourhoods in the southern and western quarters of the peninsula. Even Germaine Pelletier, the madam who operated her prostitution business at 51 Hollis Street in the seedy downtown waterfront district, knew better than to live there; her house was in a comfortable neighbourhood in the city’s west end.

By general agreement, the most prestigious street in town was Young Avenue in the city’s south end. Back in 1896, the provincial legislature had passed a law making the broad, boulevarded roadway leading to lush Point Pleasant Park one of Halifax’s first officially restrictive neighbourhoods. Under the terms of the legislation, intended “to provide that a certain class and style of house be built,” every house on the street had to cost at least $2,000 for a wooden structure, $3,000 for a brick one,” this at a time when houses in the north end sold for $600–700. In addition, “no one could put up any other building within 180 feet of the street without the approval of city council; and no one could ever use any such building for a “hotel, house of entertainment, boarding house, shop, or for sale of liquor.”

To make Young Avenue even more attractive to Halifax’s turn-of-the-century upper classes, the city spent thousands of dollars to develop and grade the boulevard, not to mention contributing $50,000 for a new sewer system. At the time it was built, the sewer system served the disposal needs of just five houses. City fathers willingly and eagerly committed such resources to the care and comfort of the affluent at a time when most streets in the working-class north end of the city were in desperate need of repair.

Such favouritism did not go unnoticed. In a letter to the editor of the Halifax Chronicle in April 1899, one correspondent, who signed himself “Maynard Street” after a working-class, north-end street, complained that “before it was criminal for a poor man to live therein, I had often enjoyed a stroll [along Young Avenue]. . . The songs of the birds gladdened the heart, and the scent of the foliage was pleasing to the smell. [Now] I know that no common north-ender is supposed to set foot within the sacred precincts of this south-end swelldom.”

This legislative attempt to keep the neighbourhood free from the riffraff didn’t last long. It was dealt its first severe blow in 1912 when the Tory prime minister of the day, Sir Robert Borden, announced plans to expropriate a swath of prime residential real estate that sliced right through the heart of Young Avenue. The confiscated land, which ran from the harbour west through Young Avenue and then hugged the edge of the pristine Northwest Arm for six miles to the edge of the city, was gouged out to make way for railway tracks leading to a new south-end train station. There were those among the Halifax aristocracy who still cursed Borden, a native Nova Scotian who should have known better, for marring the peninsula with his “volcanic fissure, miles long, filled with deep rumblings and wild whistle whoops, and emitting smoke and steam.” Worse, the construction workers not only built their temporary shacks on the edge of the railway line smack up against Young Avenue but those shacks stayed and eventually became Greenbank.

Although he was still only a child, Billy Mont already knew he didn’t belong up on Young Avenue. Or even in Tower Road School, where the children of Greenbank uneasily shared space with the sons and daughters of the south-end swells. They were kids who were going places: Robert MacNeill, who would grow up to be the famous international news correspondent and host of PBS’s MacNeill-Lehrer Report, was in Billy’s class. So was David MacKeen, the son of one of the city’s most successful corporate lawyers, who would eventually serve as an alderman and important backroom Conservative operative. Billy’s future, it seemed, had already been sealed with the pencil incident during second grade last year. His step-grandmother had sent him off to school without any pencils.

“They’ll give you pencils there,” she said.

But they didn’t. “No, we don’t supply pencils,” the teacher told him. “Go home and get them.”

Home again. Back to school again. Home again. After a while, Billy gave up. He didn’t go back to school. Eventually, the police picked him up and took him before J. Elliott Hudson, the judge in charge of the city’s youth courts.

The judge stared down at Billy from a great height. “Did you play hooky from school, young man?” he demanded.

“Yes,” Billy answered, not knowing what else to say.

Judge Hudson sentenced him to five years in the Halifax Industrial School. Billy was nine.

The Industrial School, an imposing flat-roofed, four-storey building on Quinpool Road in the city’s west end, was a cross between an orphanage and a reformatory. Founded as the Ragged and Industrial School in 1853 by a prominent socialite, its goal was to rescue street urchins and transform them into at least modestly productive members of society. The young ones attended school, the older boys learned barbering, shoemaking, the care and feeding of horses and a variety of other skills that might one day make them marketable. As Isabella Binney Cogswell, the school’s “philanthropic Miss,” explained it in one early annual report: “Many of these poor lads are fatherless, with drunken mothers, or motherless with drunken fathers, or in many cases abandoned by both parents. . . These unfortunate lads are often compelled to seek shelter in some house of ill fame, or gain a precarious living by begging or stealing or playing the tambourine at some low public house in the upper streets.”

Billy Mont, who was small for his age with olive skin and an impish grin, could have been a poster boy for the Industrial School. His biological father, a Lebanese-born boxer with the Anglicized name of Jerry Allen, had frozen to death in a refrigerated freight car outside Moncton, New Brunswick, in December 1935 when Billy was six. “Promoted by a spirit of adventure,” the front-page obituary in the newspaper declared, “Gerald ‘Jerry’ Allen, 25-year-old Halifax boxer, rode freight trains in safety on a 10,000-mile trip from Nova Scotia to California and back, but death rode with him when he attempted a 300-mile trip from Saint John to Halifax.”

In the obituary, Billy wasn’t even listed as next of kin. By then, Jerry and Billy’s mother, Mary, had long since gone their separate ways. Mary’s own troubles had less to do with the alcohol Isabella Binney Cogswell fretted about than with a simple lack of maturity. After running off to Shawinigan, Quebec, chasing after some guy or another, she and Billy eventually moved into the cottage in Greenbank with his grandfather, William Mont, a crane operator and sometime policeman at the Halifax Shipyards, and his second wife, Alice. Alice, a hard-as-nails Newfoundlander, wasn’t keen on sharing what little they had with her husband’s ne’er-do-well daughter and grandson. She didn’t seem unhappy, Billy noticed, when the judge sentenced him to the Industrial School.

Neither, truth to tell, was Billy. The food, much of which came from the School’s own garden, turned out to be better and more plentiful at the Industrial School than it had ever been at home. The kids were much more like him than those effete snobs at Tower Road. The boys, perhaps a hundred altogether, lived in dormitories, six or eight to a room. They ate in the cafeteria, roughhoused in the big gym, attended classes in the school room. There were pencils in the Industrial School’s classroom he was actually allowed to use. Surprisingly, for a boy who’d been considered slow back at Tower Road, Billy not only discovered he liked to learn but also that he was good at it.

For the first 10 months of his five-year sentence, in fact, he had been content at the Halifax Industrial School. He had never even been punished for anything. Not once. Until. . . Until tonight. The toilet? How could he have known what would happen?

“Hold still, Mont,” the voice boomed again. Billy could sense rather than see the man swing his right arm back over his shoulder. Even before the first blow landed, he could feel the tears welling up.

In the larger world beyond the punishment room, beyond the grounds of the Industrial School, war had finally begun. For Billy Mont, however, the war was the least of his worries.

***

Billy Mont could only watch in silence as nearly half of the 80 “inmates” at the Halifax Industrial School departed one by one, mostly in the company of their parents or other relatives. Six weeks earlier, Rev. Wilson, the superintendent, had written to the parents of each of the boys in his charge, notifying them that, as had become the custom at the school, their sons would be allowed to go home for three days over Christmas if the parents were willing to take them and if their boys remained on good behaviour until then.

Billy Mont had been good. With the exception of that one incident with the toilet more than a year ago, he had never gotten into any trouble of any kind at school. And he was doing so well with his class work the teacher at the Industrial School had already advanced him a grade.

Still, no one came to fetch him for Christmas this year either.

Instead, he and the other boys who, for one reason or another, would remain at the school for the holidays, attended a Christmas concert at the School. A choir from the Band of Hope, a British-based temperance organization that preached the evils of alcohol to young people, sang Christmas carols, and the six members of the school’s own harmonica band entertained with seasonal songs. Billy had liked that.

On Christmas Day, they got a special dinner of turkey with all the trimmings. There were even hard candies for a treat. But Billy would have been even happier if he could have gone home like the others.

***

No one told him anything. It had just happened. One day, Billy Mont was halfway through serving a five-year sentence in the Halifax Industrial School for having played hooky from public school, the next he was free to go. He was 12 years old.

It hadn’t been so bad, really. He’d discovered he was smarter than he or anyone else imagined. He’d squeezed three school years into the two-and-a-half actual years he spent at the Industrial School, and would be going into Grade 5 at Tower Road this fall. Better, he discovered he liked learning, if not school itself.

He’d realized other things as well. Like how to communicate using the sign language some of the other boys had taught him so they could pass messages back and forth in class without their teacher catching on. And that there was a world beyond the city. During the summers, the boys went on outings to a farm in nearby Sackville. The farm was near a race track and the boys got to watch the horses. Sometimes, an adult would go round the track in a horse and wagon, throwing candies for the boys to pick up and eat.

Occasionally, visitors would come to the School, often well-meaning religious groups like the Band of Hope, a temperance organization for working-class children. They’d lecture on the “evils of drink” and encourage the boys to sign pledges agreeing to abstain from liquor, tobacco and swearing. Billy had signed. And, except for the occasional swear word, he’d honoured his pledge. Perhaps it was simply because the Band of Hope volunteers were among his few contacts with the outside world since Alice, Billy’s step-grandmother, had succeeded in having his mother, Mary, committed to the City Home for the mentally infirm. Neither Alice nor his grandfather came to visit often.

Still, when Billy was finally released from the Industrial School, his grandfather not only allowed him to stay in his Greenbank cottage with them again, but he also helped him find a summer job at the Halifax Shipyard where Mr. Mont worked.

Billy was a boiler chipper, the dirtiest job on the waterfront. But it was tailor-made for Billy, who was still small for his age. Being a boiler chipper involved squeezing into cramped spaces aboard ships — boilers, tanks, bilges — and then using a wire brush to scrape the soot and rust and gunk off the inside walls. “The oil tanks weren’t so bad because you could at least stand up,” he would remember. “The bilges were the worst.” Billy would have to climb down a manhole cover into the crawlspace at the bottom of the ship’s hull, then work his way through a labyrinth of steel beams and posts to the even more claustrophobic confines of the bow, cleaning as he went. “It was definitely good to be small, but it was very dark. I always worried someone was going to close the manhole cover on me.”

It was almost enough to make him look forward to September when he’d have to quit to go back to Tower Road school. Almost.

***

Bert Batson put his cigar back between his teeth and picked up the small piece of sheet metal flashing, turning it over in his hand thoughtfully, as if admiring its heft. Batson knew better than to ask where it had come from, and Billy Mont certainly knew better than to volunteer that he’d ripped it off a chimney on the roof of a Water Street warehouse. Still, Billy was proud of himself. There were fewer and fewer roofs along the waterfront that he and his fellow scavengers hadn’t already picked clean of lead, metal, brass, copper — anything, in fact, that junk dealers like Mr. Batson were prepared to exchange for cash.

Mr. Batson carefully placed the piece of flashing on his scale and added weights to the balance tray to determine just how much he would offer Billy for this treasure. Some of the other scavengers claimed Mr. Batson fiddled with his scales so he wouldn’t have to pay full value for what they brought in. Billy watched carefully, but he’d never noticed anything suspicious. Some of the kids, of course, also claimed the other scrap metal dealers — Whitzman & Son and Leventhal’s, both of which were further north on Upper Water Street — cheated too. As for Billy, he simply patronized whichever shop happened to be nearest to his latest find. Today, that was Bert Batson’s From A Needle To An Anchor Scrap Metals on Lower Water Street, next door to the Nova Scotia Light & Power generating station.

Billy had become an excellent scrounger. After school, on weekends, even on his way to and from his summer job chipping out boilers at the Shipyard, Billy kept watch for items of value. His grandfather had made a carrier for the bicycle he used to ride back and forth between Greenbank and the Shipyards, and Billy kept it full of all sorts of treasures. He collected everything from scrap metal to beer bottles; they were worth a penny a piece at the Provincial Bottle Exchange just down the street from Batson’s.

Billy’s backyard, quite literally, was the CN rail yard; his playground the maze of piers, warehouses and storage sheds that snaked north along the harbour’s edge. He knew his turf; like a good farmer, he understood how to turn a profit from it.

In the CN rail yards, he staked out the refrigerator cars, climbing aboard when no one was looking and then rummaging in the ice packing for loose carrots, cabbages, lettuce, apples , anything he could sell door-to-door.

The Ocean Terminals offered an even richer cornucopia of foodstuffs for the taking. Billy knew the refrigeration system in Pier 36 would almost always break down a few times a week, so he would hang around waiting for it to happen, then join the stevedores helping themselves to the hams and meats. If he didn’t take them, he would point out, they’d spoil. Pier 27, the next wharf north, boasted a heated shed often filled with ripening bananas. Billy would wander among the crates, gathering bunches to put in his bike cart as if he were shopping in a store. Even the pigeons that lived in the sheds were fair game; he would catch them and sell them to the Chinese restaurants downtown. General Seafoods, a fish processing plant located on the Ocean Terminal docks, offered the enterprising scavenger a variety of potentially lucrative treats from the sea. For starters, there were big barrels of mackerel and herring left sitting untended on the dock. Billy would fill up his bike carrier with them and then ride through south-end neighbourhoods selling them to housewives and their domestics for 10 cents a dozen. Because the company pumped its fish waste — heads, tails and guts — directly from its processing line back into the harbour, other fish came to dine at the outfall. Billy was able to hook scores of fat fish there— halibut, haddock, and cod. “You couldn’t help but catch them,” he would remember, “and they were big too. As big as Dido.” Dido, a dwarf who also hung around the fish plant, was Billy’s main competitor for fish.

If the fish at the outfall weren’t biting or he was looking for a more entertaining catch, Billy would sometimes scoop up fish guts in a bag and head south a few blocks along the water’s edge to the breakwater beside the Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron. There, he’d dip the bag filled with bait into the water and use a scoop net to gather the lobsters attracted to it. Sometimes the old admirals from the yacht club would yell at him to go away, but, more often than not, they’d offer to buy his catch.

There were other ways to make money on the waterfront, too. Sometimes, he’d hang around the docks when the troop ships were loading. Bored soldiers would often entertain themselves tossing coins into the harbour and watching the local boys dive for them. “You had to be fast to catch them before they sank,” Billy later remembered.

His various enterprises earned him more than enough to treat himself well. Once a week, he’d stop by the Riviera Restaurant on Spring Garden Road, spend 75 cents for a hot hamburger sandwich and a Coke and have enough left over for the Saturday movie matinee — 10 cents — at the Family Theatre on Barrington, which usually boasted a double bill of a mystery and a western along with a cartoon. If it had been a good week, he’d buy a five-cent chocolate bar to eat while he watched.

Much of his other entertainment was free. Sometimes, he’d hang around outside the Woolworth’s store on Barrington Street and listen to the blind man play his accordion. At night, he’d amuse himself by climbing to the top of the huge sand pile mountain at Hubley’s Sand & Gravel near the Ocean Terminals and watching young sailors and their girls having sex. “They went there because you could hear the cops coming when they climbed up to take a look around.” The gravel pile wasn’t the only place where a curious 13-year-old boy could indulge his pubescent fantasies. There was a popular outdoor dance hall in Franklyn Park on the Northwest Arm where Billy and his friends would crawl in under the raised dance floor and look up the girls’ skirts.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the idea of going back to Tower Road School in a few weeks for Grade 6 had less and less appeal. It wasn’t that he wasn’t doing well there; he’d been near the top of his class last year. But he didn’t feel comfortable hanging out with the rich kids. When June Parker, a beautiful blond girl from South Park Street, invited him to her birthday party, he didn’t go. What would he have to say to her or any of them? He couldn’t tell them about the stamp collection he’d fished out of the trash on Young Avenue one day. Besides he’d rather fish — or scavenge — than play Red Line with a bunch of kids he was sure would look down their proper south-end noses at a boy from Greenbank.

***

Billy Mont was 14 years old. He had his Grade 6. It was time to get on with his life. His mother didn’t object when he quit school; she was already gone from Billy’s life. During her stay in the City Home, she’d met a man, got married and disappeared. His step-grandmother was only too happy when Billy landed a year-round job that meant he could contribute more to the family’s precarious finances.

If he’d had his choice, Billy would have signed up to fight overseas. But he was too young, and too physically small to convince the recruiters he was really 18. So, in the summer of 1943, he went to work for the Canadian National Railroad. It wasn’t much of a job. He and an old guy spent their days picking up papers and trash alongside the tracks outside the station or emptying and cleaning boxcars. Though his supervisor told him that if he worked hard, he might someday get to work inside the station cleaning the floors and brass fittings, or maybe, if he was lucky, even becoming a red cap and getting to carry luggage, Billy wasn’t sure he wanted to do anything but what he was doing. He hadn’t given up his lucrative scavenging sideline, and his new job offered him lots of opportunities to pick up new treasures he could sell or trade.

Why would he want to be promoted?

***

“Here, kid, I’ll boost you over.” Billy Mont glanced up at the transom above the entrance door. He would fit. Why not? He hadn’t planned to be here, but the mob had come straight at him, swallowing him in its wake. What could he do? He’d been riding his bicycle north along Granville Street zigzagging up to the Garrison Grounds to watch the promised military marching bands when he saw what looked like a human wall pushing south. Billy had heard about the troubles the night before, but he’d been too busy at the train station unloading baggage to join in the excitement. He hadn’t expected it would still be going on this afternoon. But it was. He hid his bicycle in an alley and fell in behind a group of sailors, a thousand or more, turning down Sackville and heading toward Hollis, smashing any still intact windows they encountered as they passed.

At the northeast corner of Hollis and Sackville, Billy followed some ratings into what had been Fader’s Drug Store where he helped himself to a bottle of Iron Brew, the Scottish soft drink that “provides a great taste and is truly as hard as nails.” Two doors south, he saw men, women and children, piles of clothing slung over their shoulders, pouring out of H. Star and Sons, Naval and Civilian Outfitters. Billy decided there might be a market for some of those in the south end. But by the time he’d filled his arms with suits, most of the rest of the crowd had already moved on, and Billy suddenly found himself face to face with two uniformed policemen.

“What do you think you’re doing?” one demanded.

Billy could have asked the cop what he was doing picking on a 15-year-old kid instead of going after some of the tough, drunken sailors at the head of the mob down the street, but he thought better of that. As it was, the cops just took his name, confiscated the suits and sent him on his way.

Disappointed at his failure to collect any merchandise he could peddle, Billy ran to catch up with the mob, which had now gathered outside the Hollis Street liquor store and its adjacent mail order department in numbers so thick, a reporter would note later, “a drunk would not have had room to fall down if he wanted to.” After last night’s looting, officials had boarded over the broken windows with sheets of plywood, but they were no match for the determined hordes who ripped them off and pressed into the store to finish what their fellow rioters had begun the night before. The dozen or so Shore Patrol officers who’d been dispatched to the scene as soon as the crowds began massing menacingly now stood by, helpless against the onslaught.

As the crowds surged through the liquor store looting and smashing and looting some more, Billy found himself next door outside the entrance to the mail order department. He looked again at the burly sailor who had now cupped his hands together to make a foothold so Billy could scale the wall and enter through the transom. “Get me some rum,” he demanded as Billy put his right foot in the hand-stirrup, grabbed on to the man’s hunched shoulders and heaved himself skyward. Inside, he discovered that looters had already found other ways into the mail order section and had formed human chains passing cases of liquor to their waiting comrades outside. He joined one. Less than an hour later, there wasn’t a bottle left on the shelves, though there were plenty of broken ones littering the soaking floor. Billy was sweating, and his arms were sore. Worse, he realized he had nothing to show for all his labour. He’d been so busy passing the booze along, he hadn’t managed to keep any for himself. Not that it mattered. He didn’t drink.

Excerpted from Sailors, Slackers and Blind Pigs: Halifax at War, 1939-1945.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

Thank you, Steve, for honoring Bill with this excerpt from your book. Bill was a “one of a kind” Halifax personality. It was always such a pleasure to meet him at a function and spend some time chatting with him. While I had known of his Greenbank connection, I had not known of the events of his early pre-teen years. Being the first of five generations of the Gilkie family to not be the lighthouse keeper on Sambro Island, I always kidded him about his plans for Devil’s Island. His collection of properties can only be described as eclectic.

Bill was not a personal friend ,but I did know him as an active dancer at Fairview Legion, other legions and of course at the flea markets. When I read your book many years ago, I identified with some of his tales as a Fairview boy. As to the scrap dealers , I can attest to cheating , my friend and I took a couple of deer hides to one of your named dealers , he was on Kempt road then, we went in the office, he looked over the hides and said they were not in very good condition, but for our effort, he would give us a dollar and threw them out the window, separate from the good? hides, as we were leaving the yard, we seen him reach out the window behind his desk and retrieve the hides, my older friend confronted him and he gave us two more dollars. We also fished at National Fish in the south end, because of the plant scraps as Bill said, you caught a cod most every jig. We also would take deer legs and heads to an unnamed Chinese restaurant for a few dollars, this was later than Bill, in the early 50’s.

My lobster approach was a bit different in Bedford basin along Rockingham rail yards, I was taught by a WW2 Veteran how to row our small boat along the rocks at dusk, you shined your flashlight, when you seen a lobster, you used the net with a long pole. My mother went to school with this Veteran and always approved when I arrived home with a few. My older friend did not fare as well as Bill when it came to scrap metal, he was caught with most of the lead from our school roof, taken off chimney flashings, and he was sentenced to time in Rockhead Prison at 16 yrs old. I believe Bill was the most outstanding character in your book, we have lost some living history of Halifax.

the flea market was a place where thousand people spend thier sunday

Thanks Stephen. Of course I have your book and read it with a pleasant mixture of interest and nostalgia but it was great to start my work day with re-read of the Bill Mont excerpt. I didn’t know him but it was impossible not to know of him.

How wonderful that you captured so much of Bill’s life. Thank You! Costas is right. I remember Bill when booking a table at the flea market at Penhorn Mall, to sell “stuff” to raise money for the Dartmouth South NDP. He gave me that “sweet smile”. I shall got get our book after we wrap up the Grandmothers-to-Grandmothers Market for Africa this Saturday, where we will be selling lots of “stuff” to raise money for the Stephen Lewis Foundation. Peace.

Thank you so much, Stephen. How many thousands of Haligonians have their own reminiscences of Bill over the decades? That’s not a rhetorical question.

He would occasionally visit the Upper Courtyard of the Brewery Market on Saturdays when he was well into his 80s. If a busker was playing something remotely danceable, Bill would begin waltzing his lady friend around. It always earned applause from marketeers & vendors.

I also hope anyone reading your generous excerpt will get your book.