What a difference a week — or a poll — makes.

On December 6, Corporate Research released its quarterly snapshot of the state of play in Nova Scotia politics, and it seemed to be more of the same-old, same-old, ho-hum, nothing-to-see-here-folks, move-along news story.

CRA concluded the governing Nova Scotia Liberals remained our “preferred party” with 56 per cent support — the same as it had polled in August — while the Tories (20 per cent), NDP (19 per cent) and Greens (four per cent) couldn’t scrape together enough random voters combined to come close to matching those Liberal numbers.

McNeil

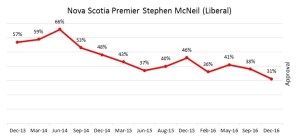

Although Premier Stephen McNeil had begun to lose some of his Teflon coating, CRA reported he still claimed the backing of 38 per cent of voters, a figure that was almost double that of PC leader Jamie Baillie (20 per cent), and left NDP leader Gary Burrill (11 per cent) and Green Thomas Trappenberg (four per cent) eating his electoral dust.

That was then.

Exactly one week later, the Angus Reid Institute released its own survey of Canadian premier popularity, asking, “Do you approve or disapprove of the performance of each of the following premiers?”

What happened?

Short answer: teachers happened.

The CRA poll was conducted between November 3–29, while Reid didn’t begin its own week of political pulse-taking until December 5.

In between — on Saturday, December 3 — Education Minister Karen Casey announced she was closing all the province’s schools in response to a decision that week by Nova Scotia’s teachers to begin to work to rule, which, in turn, had come in response to the government’s refusal to bargain with them in good faith.

Two days later, on the same day Reid’s pollsters began polling, Stephen McNeil’s government recalled, then un-recalled the legislature to introduce, then not introduce legislation to force the teachers back to work under a previously rejected contract, and Education Minister Casey herself appeared in front of reporters to wave her wand and declare that all was now well (though nothing had actually changed), and schools would re-open the next day… and then promptly disappeared again from view, along with her boss, the premier.

So those specific results may not be surprising. But what do they mean, if anything, in the larger scheme of political things?

Well, it is important to begin any discussion of political polls with the late Canadian prime minister John Diefenbaker’s response to a 1957 poll, which showed he had no chance of winning the upcoming federal election that would, in the end, make him prime minister: “I’ve always been fond of dogs,” Diefenbaker told reporters, “and they are the one animal that knows the proper treatment to give to poles.”

We should add, by way of another caveat, that while the steady-as-she-goes CRA poll was based on a sample of 801 adult Nova Scotians (accurate to within plus or minus 3.5 per cent 19 times out of 20, as the pollsters say), the Reid survey was based on a less robust sample size of just 300 Nova Scotians, creating a margin of error of 5.6 percentage points on your 19-times-out-of-20 scale.

And finally — and most importantly — polls are inevitably simple snapshots in time. And times change quickly. As if we needed reminding. Consider the last few weeks in Nova Scotia. Consider Donald Trump.

My own unscientific, un-poll-tested view is that McNeil’s broad support in the polls during much of his years in office was always more shallow than deep, more reluctant than heartfelt, more apparent than real. Voters were still recovering from a bitter break-up with the NDP. They’d never warmed to Jamie Baillie’s courting. In the long interregnum between majority government elections, they were simply parking their votes and keeping score.

Can new NDP leader Gary Burrill bring back the progressive urban NDP vote that once allowed the party to win metro’s major riding bloc all for itself? Can Jamie Baillie, who has finally re-discovered there is a progressive in Progressive Conservative, claim the middle ground in a polarizing province.

The next provincial election campaign, whenever it comes, will likely be far more interesting — and possibly consequential to the outcome — than the last twopre-determined, throw-the-rascals-out, we-have-an-alternative campaigns.

And, for political junkies, that may make 2017 worth waiting for.

Happy New Year!

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books