(“Making the Mooseheads” won an award for best sports journalism at the 2013 Atlantic Journalism Awards.)

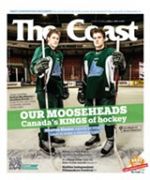

Behind the scenes of how Halifax’s junior team went from worst in the country to being the kings of Canadian hockey.

By Stephen Kimber

On Friday, April 5, at the Metro Centre, the Halifax Mooseheads—the number-one-ranked team in all of Canadian junior hockey—begin the second round of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League Championships. The team steamrolled through the first, no-need-to-break-a-sweat, tune-up round, sweeping away the Saint John Sea Dogs in the minimum four games, outscoring their opponents 25 – 4.

That this year’s Mooseheads team is special is beyond question. According to the fan website herdhistory.com, the 2012-13 Mooseheads can already claim franchise regular season records for most wins, most points, most goals scored, fewest power play goals allowed and most games in a row—43—in which the team earned at least a point. The 2012-13 team had more 30-goal scorers (five) and more 20-goal-scorers (eight) than any previous team. Its flashiest forward, Jonathan Drouin, set a record for the longest consecutive point streak at 29 games, and would almost certainly have won the league scoring championship if not for injuries and the mid-season month he spent dazzling fans at the World Junior Hockey Championships in Ufa, Russia. Not to forget the Mooseheads brilliant young goalie Zachary Fucale, who now owns team records for most wins in a season and best goals-against average.

Not bad for a team that, three years ago, was not only the worst in the league but, according to its owner, the “worst team in the country.”

How did the Mooseheads get from there to here?

And is this—after close to two decades of respectable futility—the year they win it all?

There are any number of places where this story might begin, but let’s start in California on a sun-drenched summer day almost two years ago…

***

“Yes, well… that’s great,” Graham Mackinnon responded coolly, calmly, to the voice at the other end of his cellphone. “Thanks for letting us know.”

It was the morning of July 13, 2011, and Graham, his wife Kathy and their two teenaged children—Nathan, still almost two months’ shy of his 16th birthday, and Sarah, Nathan’s 17 year old sister—were on an L.A. Freeway in a rented car headed for a day at the beach.

Nathan was in California to attend a summer camp his advisor-agent, Pat Brisson, organized each year for his most promising young hockey prospects. Kathy and Graham had decided to make it a family vacation—in part to escape, if only for a few days, Nathan-crazed Halifax. Back home, Nathan’s future had become a matter of fevered, obsessive conjecture. “It was frustrating,” Kathy would recall later. “Why was everyone talking about what we’re going to choose?”

Not that Kathy was unaware of the significance of the choice she, her husband and their son would soon make. The family had set August 1st—less than three weeks away—as Decision Day.

Nathan MacKinnon wasn’t just another talented young hockey player. From the time he was seven or eight, everyone knew he had that magic elixir of natural talent and unnatural obsession that could take him… wherever he chose. At age 12, a year or two younger than his teammates on Cole Harbour’s Bantam AAA Red Wings, Nathan scored 110 points in 50 games. The next year, he scored 145. “I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if he could go to university and play, and maybe get a scholarship?’” Kathy says. “My husband was more forward thinking.”

It was Graham, in fact, who’d suggested, two years earlier, that Nathan attend Shattuck-Saint Mary’s, the Minnesota prep school and professional hockey incubator fellow Cole Harbour hockey player Sidney Crosby once attended. Kathy especially liked the fact hockey was integrated into Shattuck’s curriculum; if you were late with an academic assignment, you’d hear about it from the coach. For Nathan, a “hockey-is-who-he-is” kid but an average, “happy-to-get-Bs” student, Shattuck represented—for his mother at least—an ideal place to develop and mature as player, student and man.

Having completed grades 9 and 10 at Shattuck, Nathan was scheduled to start Grade 11 in September. Under U.S. National College Athletic Association (NCAA) recruitment rules, that meant already-slavering American university scouts would finally be allowed to talk to him. You didn’t have to look far—one of the banners hanging from the roof at the Shattuck hockey arena honoured Jonathan Toews, a school alum who’d gone on to play college hockey before starring for the NHL’s Chicago Blackhawks—to see where that might lead. Shattuck, says Kathy MacKinnon, “certainly didn’t seem like a bad place for Nathan to spend the rest of high school.”

But it was far from his only option.

Just over a month before—on June 4, 2011—the Baie Comeau Drakkar of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League had made Nathan its first overall selection in the league’s annual draft of the best 15- and 16-year-old midget hockey players from eastern Canada and the United States. The QMJHL, one of three elite junior hockey leagues in the country, represented the traditional rite of passage for Canadian boys who aspired to play professional hockey.

But it was no longer their only pathway.

In fact, Nathan and his mother had skipped the high-profile QJMHL draft day in Victoriaville, Quebec, the month before and drove instead from Shattuck to Omaha, Nebraska, to check out the Lancers, a junior team in the United States Hockey League. The USHL had not only begun to rival Canadian major junior leagues as an NHL training ground (more than 150 grads play in the NHL) but, just as importantly, it also served as a gateway to Division 1 American universities (close to 250 young men each year made that leap). After a day scrimmaging with the Lancers, Nathan reported the hockey “very competitive.”

In Omaha, he could play against elite older players while retaining his NCAA option.

That option would disappear if Nathan decided to play for Baie Comeau, or any other QJMHL team. Making Baie Comeau less appealing—from Kathy’s perspective—the team didn’t send its kids to local schools, preferring instead to arrange for them to take correspondence courses and attend team tutoring sessions. “I worried Nathan could end up the only English kid in a room taking correspondence courses,” she explains. “After Shattuck, we weren’t willing to take that chance.”

That was one reason they’d skipped the QMJHL draft. “If he’d gone there that day,” his mother says, “it might have seemed like we were committed—and we weren’t ready to commit.”

But the MacKinnons knew at least one other QMJHL team—the hometown Halifax Mooseheads—were also fishing for his future services.

If the Mooseheads landed him… well, that would change everything.

Back in the rental car on the LA freeway on the way to the beach on July 13, Graham listened to the voice at the other end of the line. “Sure,” he said into the phone, then handed it to Nathan, smiling. “It’s for you. It’s Cam.”

***

Cam Russell—another Cole Harbour lad who’d enjoyed a successful NHL career before retiring home to Nova Scotia—had run summer hockey schools Nathan attended. Russell—now the Mooseheads’ general manager—was just one of the family’s many connections to the team. When Nathan was seven, the family had billeted Mooseheads forward Frederic Cabana. Later, goalie Jeremy Duschene stayed with them. Nathan himself had been a member of Hal’s Pals, a kiddie fan club.

“We got to know the organization,” Kathy MacKinnon says, “and we were impressed by the way they operated.” Including, of course, their emphasis on education.

If Nathan could play for the Mooseheads, it would have been “a no-brainer,” Kathy says. “Nathan could have what he wanted—a chance to play and develop his skills with a good organization—and I could have had what I really wanted—my son at home again.”

The Halifax Mooseheads wanted—needed—Nathan MacKinnon to play for them at least as much as the MacKinnons wanted their son to play for the Mooseheads.

The Mooseheads had been in the league for close to two decades and—though the team put on respectable showings most years—it had yet to win a league championship, let alone a Memorial Cup, the holy grail of Canadian junior hockey. The closest they’d come—twice—was getting to the third of four rounds in the QMJHL championships. In 2000, they’d played in the Memorial Cup, but only because host teams automatically qualify for the tournament. The Mooseheads were eliminated in the semi-finals.

Their last—worst—major disappointment had come in 2007-08. That year’s already talent-rich team had traded away five future draft picks, including two first-rounders, for Brad Marchand, another local boy-then-making-good, believing he was the final piece in their Memorial Cup puzzle. Instead, the team was swept in four straight games in the third round of their league playoffs, and Marchand was such a bust he was benched for the final playoff game.

Some Mooseheads fans will tell you—retrospectively, of course—that was the best thing that ever happened to the team. After years of doing whatever it took to be in the muddling middle of the league pack but never quite enough to win it all, the Mooseheads had gambled—and lost.

The team went from first in their division to last in the entire league two years in a row. That should have allowed the team to rebuild by choosing the best young players available in the next years’ drafts—last place teams pick first—but the Mooseheads had already traded those picks away.

On January 14, 2009, the team’s new owner, former NHL star Bobby Smith, fired general manager Marcel Patenaude and appointed Russell, then the coach, to assume the dual mantle of coach and general manager.

“That was the day the rebuild began,” Russell says today. He and Smith agreed the team would stop trading future prospects in order to remain just OK; they would take their lumps and swap veterans for draft picks, building a contender from within.

In the short term, it didn’t help. There was more bloodletting. In October 2010, Bobby Smith “relieved” Russell of his coaching duties, briefly, quixotically, taking over the reins himself, but asked Russell to stay on as general manager to continue rebuilding the team. “That was a difficult day,” Russell admits, but he sucked it up. “We’d started something, and I wanted to see it through.”

By then, Russell had put many of the building blocks of what would become the 2012-13 Mooseheads in place. In 2009, he’d drafted forwards Carl Gelinas, Brent Andrews and Matthew Boudreau, along with defencemen Steve Gillard and Trey Lewis. Lewis, now the Mooseheads’ 20-year-old co-captain and one of its steadiest defenders, was chosen with a late-in-draft-day 67th overall pick. “Our scouts,” says Russell, “are very good at their jobs.”

In the draft of top European prospects the next month, the Mooseheads added gangly German defenceman 16-year-old Konrad Abelsthauser, now a San Jose Sharks NHL draft pick.

After wheeling and dealing a stockpile of five of the first 37 picks for the 2010 draft, Russell added forwards Luca Ciampini, the second overall pick, Andrew Ryan and Darcy Ashley, then topped up his talent pool in the European draft with 17-year-old Czech scoring sensation Marty Frk. (The next year, Detroit would confirm Frk’s worth, selecting him in the second round of the NHL draft.)

While Russell believed he had put together the core of a winning team, he knew he needed something more to transform it into a true championship contender. He needed Nathan MacKinnon.

***

The Halifax Mooseheads had never had a homegrown superstar. They’d missed out on Sidney Crosby, who’d played his junior hockey in Rimouski, Quebec, and James Sheppard, a Lower Sackville boy who set his junior hockey records in the uniform of the Cape Breton Screaming Eagles.

“We didn’t want to miss out again,” Russell says simply.The problem was that Baie Comeau, the league’s second worst team the season before, had won first draft pick in a coin toss. They weren’t about to trade away the chance to select MacKinnon, even after his parents made it clear Nathan wouldn’t report. Baie Comeau gambled that, even if it couldn’t eventually convince the MacKinnons the Drakkar was the team for their son, other teams would bid up the price for him after the draft.

The best the Mooseheads were able to do before the June 2011 draft was trade with another team to get the second pick (as fourth worst team the season before, they were scheduled to choose fourth).

With that pick, Russell chose another budding superstar named Jonathan Drouin, who would turn out to be far from a consolation prize.

But Russell also scored another draft-day coup. The Lewiston Maineiacs, the only American-based team in the QMJHL, had dropped out of the league at the end of the season, and their players—and future picks—were up for grabs by the league’s other teams in a dispersal draft. Russell had the opportunity to add an experienced 53-goal scorer, but opted instead to take the Mainieacs’ first-round pick—11th overall—in the next day’s midget draft. He used that pick to choose Zachary Fucale. “We had our goalie coach watching him all season and he was a consensus No. 1 for us,” Russell told reporters later. “You look around the league and you can’t win championships without good goaltending. That’s why it was important to get that 11th pick. We knew there were other teams that were very high on him.”

Russell had his goalie of the future, his two key European picks, a budding superstar in Drouin and a cast of talented prospects who’d spent the past two seasons learning to play together.

Now all he needed was Nathan MacKinnon.

***

In the weeks following the draft, Russell worked the phones, talking two, sometimes three times a day, with Steve Ahern, Baie Comeau’s general manager. Probing, proffering, feinting, making offers, fielding counter offers—How about Jonathan Drouin, plus, plus?… No deal—cajoling, bullying, shouting, hanging up, calling back. After it was over, Russell would call Ahern to apologize for things said, and unsaid. “These discussions can get pretty emotional,” Russell allows.

By early July, Russell understood the outlines of what Baie Comeau wanted—both draft choices to help their team rebuild and also one or more proven veterans who could make the team respectable immediately.

On July 12, Russell landed those draft picks in a separate deal with the Quebec Remparts. The Mooseheads dispatched a young American player named Adam Erne—another Mooseheads’ top 2011 draft pick, but one who’d indicated he was unlikely to report to Halifax—to Quebec in exchange for the Remparts’ first round picks in 2013 and 2014, and a 2012 second round pick.

The next day, Russell packaged those first-round picks with another first rounder from his own collection, and sweetened the pot by including Carl Gelinas, a class of 2009 Mooseheads draft pick who’d blossomed into the team’s most valuable player, and Francis Turbide, a solid defenceman.

Done.

After the official announcement was arranged, Russell asked for—and got—permission to be the one to call the MacKinnons to convey the good news.

Talking on the phone on the freeway in L.A., Nathan kept his composure, thanked Russell for his efforts, said he was excited to play for the Moose. It wasn’t until after he hung up the phone that the family looked at one another and, as Kathy puts it, “started screaming ‘woo hoo’ all the way to the beach.”

They weren’t alone. Within minutes, Mooseheads’ staff were fielding calls from newly fantasizing fans eager to buy season tickets.

Everything was finally in place.

But then, just over a month later, on the eve of the team’s training camp, Jonathan Drouin’s family unexpectedly informed the Mooseheads he wouldn’t play for them that season.

***

What makes junior hockey so endlessly entertaining, frustrating and unpredictable is that it is played by teenaged boys who are themselves endlessly entertaining, frustrating and unpredictable.

Russell and the Mooseheads’ new head coach, Dominic Ducharme, immediately flew to Quebec to try to persuade Drouin to change his mind. But his parents, his agent and his midget hockey coach had apparently decided Jonathan, still physically slight, could benefit from another year of maturing as well as another year in his local school.

“It came out of the blue,” Russell admits now. Though publicly accepting—“These are his wishes and we’ll respect them,” Russell told reporters—Mooseheads scouts remained in constant touch with Drouin, attending his every game. Russell himself checked in with the family weekly and made frequent face-time visits. “By Christmas,” Russell says with an exhale, “Jonathan was ready to make the jump.” He pauses. “It was a huge relief.”

***

At one level, junior hockey players are professional athletes who train year-round, practise daily and play a relentless 68-game schedule in front of demanding fans who treat them like heroes—or bums, often both at the same time. They’re expected to live up to their exalted status off the ice too, making public appearances, visiting schools, sick kids in hospital… If they don’t perform, they can find themselves traded or, worse, cut.

And yet… they’re also 15 and 16 year olds coping with life in a new city, a new school system, often a new language, trying to make new friends. They’re boys who miss their mothers, teenagers whose girlfriends break up with them, students whose essays are due Monday morning, kids who sometimes do stupid, fun things they wouldn’t want their parents to read about in the newspapers…

To complicate matters, they’re also still developing, both physically and emotionally. “There’s no guarantee that the best player at 15 will still be the best player at 19,” Russell admits.

Shaping a winning team out of that messy clay is no easy task. And it must be done in three-year cycles because—unlike professional teams—junior players are only eligible to play between the ages of 16 – 19 (each team is also allowed three 20 year olds). And rare talents—like MacKinnon and Drouin—often end up graduating to the NHL at 18.

Which means…

This year’s team may be the Mooseheads best chance to win its first ever league championship, perhaps even its first Memorial Cup.

Can they?

Cam Russell remembers what happened back in 2007-08. He knows how unpredictable teenagers are, how fickle the hockey gods can be. He laughs. “We’ll see,” he says.

Stephen Kimber’s latest non-fiction book, What Lies Across the Water: The Real Story of the Cuban Five, will be published in August. When he’s not “researching” in sunny Cuba, Kimber attends Mooseheads games as a long-time season ticket holder.

(From The Coast, April 4, 2013)

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

Luckily, I didn’t become a chemist! Great to hear from you after all these years. Hope you’re well.

Hi Stephen:

I went to highschool with you and was your chemistry partner. We had lots of laughs then. I might have known you would become a writer! Nice to see what you have accomplished.

Julie