“Encounter on the Urban Environment,” 1970, became the week that shook Halifax to its core

“In the final week of February 1970, 12 specialists—most of them men of international reputation—gathered in Halifax, Nova Scotia, to take part in an experiment utterly new to the Western Hemisphere,” wrote Ken Hartnett, a Washington-based urban affairs reporter for Associated Press. “Their assignment, although it was never explained to the 12 in precisely these terms, was to take a community of 250,000 persons and turn it upside down.”

“Encounter on the Urban Environment” was the unlikely brainchild of the province’s Voluntary Planning Board, a citizen’s policy advisory forum set up by the Stanfield government and made up mostly of members of the local establishment.

“I told [the board] exactly what was planned [for Encounter] and what the likely implications were,” A. Russell Harrington, the president of Nova Scotia Light and Power Co. and the chair of the planning board, explained later. “And they didn’t believe me.”

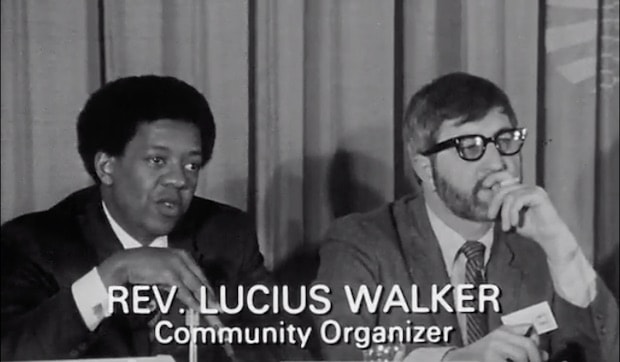

Over the course of a week, the carefully chosen experts—six from Canada, five from the U.S. and one an American working in England, whose day jobs ranged from economists to black community organizer to industrialist to labour leader to journalist—spent exhausting days and nights meeting, listening, sometimes cajoling or arguing with Haligonians from every strata of society about what their city was and what it could be. The process allowed the traditionally powerless to finally have a voice and forced the powerful to listen, and respond.

Why were there no black faces working at Volvo, the Swedish car maker that had been lured with taxpayer dollars to set up shop in north-end Halifax cheek by jowl to a black neighbourhood? Why did Industrial Estates Ltd., the province’s business development agency, have such a lousy “batting average” when it came to attracting development to the provincial capital? Why were so few affordable housing units being built? Why was the city’s daily newspaper failing to cover what was really happening in the city? Why was the school system so awful? And why had the police really raided that radical educational commune attended by the police chief’s daughter? Why was the new container pier in a location everyone agreed was at the wrong end of town? Why had the city razed the poor but proud black community of Africville? And “what the hell has the new Human Rights Commission done about Africville” anyway?

What made the process so powerful was that the questions—parochial, petty, sometimes profound—got asked and occasionally answered in the full glare of television cameras. Finlay MacDonald, the owner of CJCH Television and one of the organizers of the Encounter process, broadcast the team’s nightly town hall meetings live. With only two English language television channels to watch, the sessions quickly became must-see events for Haligonians. No one knew what might happen next, or who might say words not otherwise permitted on television.

Although it is difficult to pinpoint specific changes that resulted from Encounter, there is no question the process engaged a previously apathetic citizenry in the affairs of their city.

Excerpted from

Halifax: Warden of the North (Updated Edition)

by Thomas Raddall and Stephen Kimber

Nimbus Publishing

For more information, there is an NFB documentary about the week.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books