A deferential Canadian columnist, with modestly Canadian smugness, tries to answer that question.

On Thursday morning, as is my wont, I was reading “The Morning,” my daily email briefing of all the news the New York Times deems fit to digitize. Think of it as the Americans’ attempt at the Examiner’s “Morning File.” Or perhaps it is the other way around.

But I’m Canadian, so allow me to see the world my way.

You won’t find much about Canada in the Times version, of course, so when the word “Canada” appears anywhere in this venerable American journalism institution, I pay attention. You may think of it as envy. I prefer smug… er, pleased they noticed.

On Thursday, I was greeted with my usual cheery “Good Morning” from editor David Leonhardt, followed immediately by the cold slap of the latest global news headlines: “France and Germany impose new lockdowns. Hurricane Zeta hits the Gulf Coast. And not all virus outbreaks are the same.”

There was an eclectic collection of other items of note, of course, all with requisite links to stories in the Times that day. Among them:

- the train wreck of a US presidential election now bearing down on that country like a runaway Shanghai Transrapid. Transrapid? It’s the fastest train in the world. It is. I know; I looked it up on the internet.

- Yet another curfew and still more protests in a random American city, this time in Philadelphia following yet another shooting of yet another black man whose life didn’t matter enough.

- 13 new books to put on your reading radar for November.

- the Los Angeles Dodgers’ World Series-clinching victory the night before, which put an end to the choker label affixed to pitcher Clayton Kershaw, who won two games when it mattered, and the beginning of the superspreader tag on third baseman Justin Turner, who rushed onto the field to celebrate with his teammates minutes after he’d tested positive for coronavirus.

- and a tribute to Cecilia Chiang, the restaurateur who “introduced Americans in the 1960s to the richness and variety of authentic Chinese cuisine,” and had now died at the age of 100.

Still, I couldn’t stop my eyes from being drawn back to the day’s inelegantly titled lead item: “Where the Virus is Less Bad.”

Above the headline was an iconic 2020 back-to-school photo — a family of four, dad holding an infant, mom hand-bumping with a masked little girl, her pink backpack beside her, as they stood by the side of a road waiting for the school bus, all set against an unmistakable landscape of… wait for it. “Parents sent their daughter off to school in Prince Edward Island, Canada, last month,” the caption read.

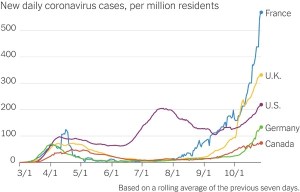

In this item — about the reality that there are better ways than Donald Trump’s science-free, “rounding the corner,” “it will disappear” approach to the coronavirus — Canada was not just a random photo illustration. We were also graph stars!

“Two countries are worth some attention: Canada and Germany,” noted the Times as it opened up a discussion of why those countries are “doing a lot less bad” than the United States.

Notes me, the Canadian. We got first billing in that sentence!

Better, while acknowledging that neither Germany nor Canada has escaped a fall surge in COVID cases, the Times suggests “Canada may be an even better example” of how to wrest control of the virus from the virus.

The Times points out that in Canada, our gently hectoring public health officials — wear your mask, keep your distance, wash your hands — have become “semi-celebrities.” Better, even populist right-wing political leaders like Ontario’s Doug Ford have refused to dismiss mask-wearing as safe houses for sissies. Ford, writes the Times approvingly, even called out those who protest social distancing measures as “a bunch of yahoos.”

Granting that Donald Trump has set the bar for political courage well below the low water line, one might see such praise of our political class as damning with faint comparative praise, but I’ll take it as written. I’m a Canadian, after all.

And, better, an Atlantic Canadian. The Times again:

Among the most successful Canadian regions have been the four small provinces along the Atlantic Ocean, all of which have almost extinguished the virus. They have done so by largely closing their borders — a strategy that has also worked in several other countries, including Australia, Ghana, Taiwan and Vietnam, despite skepticism from some political liberals around the world.

The four Canadian provinces — Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and the combined Newfoundland and Labrador — were successful enough this spring that they were able to form a joint “bubble” this summer. Residents can travel among the four, even as they remain closed to the outside.

Those two paragraphs generated a number of emails from my Times-reading American friends, eager to know how we did it, and how they too could join our little bubble.

All of which, of course, raises the question. What is it about Canadians that makes us different from Americans?

The Times’ Leonhardt, as Times editors often do, called on another Times reporter to make sense of it all:

Some of Canada’s success is probably cultural and would have been hard to replicate in the U.S., as Ian Austen, a Canadian who has covered the country for The Times for more than a decade, told me. “There is generally a lot of deference to authority in Canada,” Ian said.

OK, that solves that. It says so in the Times, so it must be so.

But… are there other ways we might frame that explanation to make us seem less like meek Canadian milquetoasts compared with our steel-willed, undeferential cousins?

How about this? Canadians believe, however deferentially and reticently, and acknowledging that not all of us will agree — we are still Canadians, after all — in the value of a collective public good.

- It is why we have a publicly funded, universal health care system, even if it isn’t funded as well as it should be, and still doesn’t cover nearly as much as Canadians need and want.

- It is why we wear masks, even when it’s inconvenient and uncomfortable, because it might keep someone else safe, and because we understand that keeping someone else safe keeps us all safer. Ditto for distancing.

- It is why we defer to the best science available in the moment, knowing the science will change and evolve, and we will change and evolve with it, but it is still the best science available at the time, and for the time.

- Because we believe in a collective public good, we don’t believe every individual has the inalienable, God-given right to carry her or his assault-style weapon into a legislature, or synagogue, or voting booth, so they can open fire on those they disagree with.

- At the same time, we do accept certain inalienable individual human rights within our collective common good: a woman’s right to choose, for example, and an individual’s right to define their own gender or sexual orientation.

- That collective public good is also why we believe, again imperfectly, in the value of truth and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, of immigration and multiculturalism, of protecting the planet for the future before there isn’t one.

Not all of us, of course. And not all the time. As Canadians, we must always qualify what we say. But enough of us. Enough of the time.

Which is why — deferentially, of course — we modestly smug Canadians wish all our American friends an improved collective outcome after this week’s US presidential elections.

Our global collective — and individual — goods depend on it.

A version of this column originally appeared in the Halifax Examiner.

To read the latest column, please subscribe.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

I enjoyed reading and learning from this article.Please,keep writing and sharing more about Canada and its humble people In Cuba,we feel special sympathy for you all.sincerely.