“….Yvon Durelle, the New Brunswick boxer best known for his epic battle with one of the sport’s greats, Archie Moore, died Saturday in Moncton. He was 77….”

In the early 1980s, I wrote this profile of Yvon Durelle for Atlantic Insight magazine…

Profile

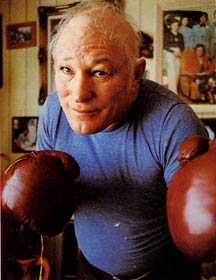

He’s 50 now. His night to remember was 22 years ago. He laughs a lot, cries a little but, either way, puffiness closes his eyes. A hard but gentle man who’s led a hard but ungentle life, he is still

Yvon Durelle, fighter

Outside, a dusting of new snow freckles the hard earth of Baie Ste. Anne, N.B. A streetlamp lights up the parking lot and renders eerie and somehow sad the sign above the padlocked building behind it. The sign announces that the place is The Fisherman’s Club, but it also bears a portrait of a dark-haired, square-jawed young man. He stares out into the night, his fists poised in a traditional boxer’s stance. The cars and trucks that hurry past that scene on this winter night do not slow down. Their occupants do not glance at the determined face of that young man frozen in a time long ago and far away, and they do not bother themselves to wonder what has become of him.

His hard, flat, boxer’s stomach is still hard, but it’s no longer flat. His hair has almost all fallen out, and what remains is as white as the snow outside. “It fell out after ‘the trouble,’ ” he explains cryptically. A neat scar —the result of a recent operation to ease the pressure from a jaw that was once crushed back into his head by a fist and never previously repaired — traces a line across the back of his scalp. His voice is throaty and sometimes he thinks too fast for his words. He has to repeat himself to be understood.

“I’m not punchy, I’m not crazy. It was just ‘the accident,’ ” he explains, reverting to the private code he favors. The skin around his eyes, cross-hatched with scars from stitches, is puffy and outsized. He looks vaguely Oriental and unmistakably menacing, but when he laughs or cries, the puffiness closes his eyes and he looks childlike. On this night, the eyes have been shut often with laughter for the good times and tears for the bad. The bad times far outnumbered the good, but in the remembering there’s more laughter than tears.

We are sitting at a kitchen table piled high with memories and beer bottles. He has shown me his tattered press clippings and his scars. He has bragged about fights for which there are no records. (“Yvon has a tendency to exaggerate,” a friend says. “If he told you he had 291 fights, you can probably cut the number in half and be close to the truth.”) He has boasted about exploits to which there were no witnesses. He has taken his ring (size 19) off his finger and demanded that I put it on my thumb. It hangs loose like a bracelet. He has hauled out the yellowing teletype roll of a telegram. It weighs four pounds, three ounces, he tells me proudly. It’s half a mile long. It contains the names of 11,700 east-coast boxing fans who just wanted to let him know on that December night in 1958 when he fought Archie Moore for the world-light-heavyweight championship-that they were rooting for him. The telegram is still ,his most prized possession. “I’d

like to meet those people sometime,” he said as ‘he stuffed the roll back into its plastic bag. “I’d like to thank them.”

Now, however, he is fiddling with a troublesome tape recorder. He wants me to hear a cassette of a radio documentary the CBC put together about him. “Open up some more beer,” he orders as he tries to press small buttons with meaty fingers. He’s told me he doesn’t drink much anymore. “In the beginning I was, you know, a heavy drinker, but I don’t need it anymore. It doesn’t achieve nothing.” But tonight is a special occasion. We’re talking about the old days. About the good times.

Durelle flips off the tape machine.

“I’m proud of that fight,” he says in a voice that is a mixture of gravel and fondness. “I fought the best in the world and I fought goddam hard. I was beaten by a better man, that’s all, but I did the best I could and I’m goddam proud of myself.” Durelle has an old, scratchy film of that fight. He has seen it a hundred times or more. Each time he discovers something new: A long count that denied him victory, a moment when he should have hit and didn’t, an instant when he might have backed away but didn’t.

But nothing he sees now can change the fact that Archie Moore rallied from the shock of being knocked down three times in the first round and once more in the fifth, and hung on until he was able to put Durelle away in the 11th round. “All Mr. Durelle had to do,” Moore said later about those early rounds, “was blow against me, and I would have been gone.” Durelle had come within whispering distance of boxing immortality, but the record book is deaf to whispers. All it says is, “World light-heavy title, Archie Moore, KO by 11, 12/10/58.”

Durelle sits down again in his chair and pours his beer. Tippy, his chihuahua, climbs up, snuggles in his master’s arms. “Try and touch me, go on, just try,” Durelle tells me. I reach out for his arm. The tiny dog snaps and growls and lunges for my hand. Durelle laughs, delighted. “No one touches me, not even my wife. The dog loves me. She’s like a kid. I love that dog.”

Durelle takes a long swallow of beer. In spite of all the awful, crazy, sad, and ultimately incredible twists of fate that have turned him upside down and twisted him inside out in the 21 years since he fought Archie Moore, he will tell you today that he is as happy as any man has the right to expect to be. “I don’t owe nobody nothing. I’m not rich in money but in happiness, I’m wealthy.” He smiles and the eyes close again.

“I got some money put away so I don’t have to work if I don’t want to. The house is mine, the kids are gone and there’s just me and the wife. We sit at home and watch the TV at night and I’m happy. Every day I go to Chatham and I have coffee with my friends and then I come home and I have my wife and my dog.” He is silent for a long moment, the eyes still closed. “I’m a proud man, you know. I’m proud of myself and I’m happy.”

It’s hard to believe.

The color of almost all the days that have slipped away from him since December 10, 1958, has been unrelieved black. His troubles began almost from the moment he stepped out of the ring that night, a beaten but heroic Rocky-like figure, the simple fisherman who had almost stolen a world boxing championship and brought it home to Baie Ste. Anne. Before his rematch with Moore the next summer, however, Durelle smashed his spine in a boating mishap (he refers to it as “the accident”) that cost him his balance and made him a wobbling punching bag for the sure-footed, smart-fisted and no longer cocky Moore. Durelle was gone in three quick rounds and soon, reluctantly he was gone from boxing as well. His doctor had warned him that if he continued to fight “neither heaven nor hell will be able to help you.”

He spent the next decade as a forest ranger, earning $50-odd a week and ignominiously making ends meet by picking up spare change as a wrestler. At the end of his day’s work in the woods, Durelle would get into his Volkswagen and drive to Moncton or Halifax or wherever it was that the show had to go on that night, force himself to go through the motions of grappling with the likes of Bulldog Brower or Killer Kowalski, and then hop back in his car for the long drive back to Baie Ste. Anne and another day as a forest ranger. In a good week, he might clear an extra $200 for his trouble.

Durelle did it because he needed the money. There were still four kids to feed, clothe, and educate and, worse, there were also those grey-suited men with their adding-machine minds. They were from Revenue Canada and they were convinced Durelle had neglected the nicety of reporting all the money he made as a boxer. As soon as he left the ring, they began hounding him for the state’s share of the take from his glory days. But, by the time they caught up with him, the glory days were long gone and so, too, was whatever money there might have been.

Durelle says he still doesn’t know how much he made in the ring or where it all went. He cheerfully admits he knew good times, gambling, and gallons of whisky, but he also knew any number of fast-talking hustlers and money-grabbing hucksters. They are as much a part of pro boxing as the smell of stale sweat and cigar smoke, and they made off with more than their fair share of his winnings. When Durelle finally settled up with the income tax officials in the early ’70s for $2,500, he had to borrow every cent of the payment.

His luck at last seemed about to turn in 1972. Oland’s Brewery hired him to tell his boxing stories and peddle their beer on the north shore of New Brunswick. But one night in 1973, his house in Baie Ste. Anne burned to the ground. He lost almost all his possessions. A few months later, during a company reorganization, Oland’s let him go.

Trading on what was left of his fast-fading boxing reputation, and desperate to make a few bucks, Durelle wangled a liquor licence and a loan for $40,000 in ’74, and opened The Fisherman’s Club next door to the new house he had built in Baie Ste. Anne. His battered boxing gloves hung behind the bar and Durelle regaled the crowded club with tales of times they all remembered while the beer flowed as though there were no bottom to the barrel. He began to make money again and this time there were no zealous auditors sniffing around the books for signs of mischief and no hustlers trying to steal it from him. He was happy. Of course, it couldn’t last.

On an April night in 1977, Durelle pumped five bullets from a .38 calibre revolver through the window of a car in the parking lot of The Fisherman’s Club, and Albin Poirier, a 32-year-old sometime fisherman from Baie Ste. Anne, was dead. Durelle claimed the man had been harassing him and threatening his family, that he had fired the gun in self defence because Poirier was trying to run him over with the car. Although the jury took just 50 minutes to acquit him of a charge of non-capital murder, the ordeal frazzled Durelle’s already jangled nerves. He had nightmares. His hair fell out. He broke out in a sweat whenever he thought of The Fisherman’s Club. In the spring of ’78, he sold the place. Today, he refers to the incident only as “the trouble” and whenever he tries to talk about it, he begins to cry. He switches the subject.

“You say there was a fight tonight? I wish I’d known.” While we were drinking beer in Baie Ste. Anne, Trevor Berbick of Halifax was slugging it out with a Nigerian in an elimination bout for the Commonwealth heavyweight boxing title. Despite the two decades that have disappeared since Durelle retired from the ring, he is still occasionally invited to be at ringside or to referee at pro boxing matches. In St. John’s one night, the crowd gave him a 15-minute ovation. They did the same in Winnipeg last October. “It bothers me, it’s so nice,” he says. “I choke.” But on this night, he hadn’t even been invited to Halifax to sit at ringside and hear the adulation of the fans. The neglect hurts him more than a fist in the face. “I’d have gone,” he tells me. “I got nothing else to do and, you know, I still like the fights.”

He was born with that love of “the fights.” The sixth of 13 children of a poor fisherman and his wife, he still remembers fighting for his supper. Literally. “Me and my brothers, we’d fight like hell to see who would get the supper. The loser went to bed without any.” Durelle loved to fight. He tangled with his brothers in the woods behind their home, he tussled playfully and “for nothing” with school chums at the side of the school, and he would slug it out with any anglo tough from Hardwicke or Escuminac who was brave enough or crazy enough to venture into Baie Ste. Anne.

Like most New Brunswick francophones of his generation, he grew up in linguistic and cultural confusion. At home, he spoke French, but at school his teachers and his schoolbooks were English. He dropped out after Grade 3 and only later taught himself to read and write — in both English and French so he could read his press clippings.

Out of school, he worked on his father’s fishing boat and toned his muscles shaping the anchors that his father made in his own blacksmith’s shop. Durelle was just 14 when he fought his first official bout, a three-round exhibition fight in a makeshift ring in a farmer’s field at Baie Ste. Anne. He won and, a month later, turned professional. “I weighed 115 or 120 pounds then,” he says with a laugh. He has since added 100 pounds. “But fought like hell. I loved to hit people over the head.” He knocked out his first opponent in his first pro bout at the old Opera House in Chatham and earned eight dollars for his trouble. Soon he was a featured attraction all over New Brunswick’s French shore.

“I can remember my father sitting by the stove with his feet in the oven and listening to Yvon’s fights on the radio,” remembers Therese Durelle, Yvon’s wife and rock-solid centre for almost three decades. “My father would get so excited, his legs would shake. I didn’t know what all the fuss was about.” She did know, however, after their first date, that she would marry him. “I knew there was only one guy I cared for,” she says. “He was — how do you say it in English? — doux. He was very sweet. I still call him that. ‘Doux’ is his nickname.” Yvon still calls Therese “Ma’am.” They were married in 1951.

By then, Durelle was spreading his fistic reputation all over the Maritimes. In his first decade in the ring, he lost only four fights (one on a foul), and in 1953 in Sydney he beat Gordon Wallace for the Canadian light -heavyweight title. Four years later, he won the British Empire crown and decided he was ready to challenge Archie Moore for the world title. He did not always win. His official ring record stands at 44 knockouts and 38 decisions in 105 fights, and he was knocked out by the likes of Floyd Patterson, Jimmy Slade, Yolande Pompey and George Chuvalo, as well as by Moore. But his fists were always fearsome.

“I hit the whites until they turn black and the blacks until they turn white,” was the way he once described his boxing strategy and, in truth, he was a brawler without style. He rarely trained for his fights, he was often overweight and he knew almost nothing of finesse. But he would give a punch and he could take a punch and he loved to do both. “Yvon was an 80% natural fighter,” says Chris Shaban, his old friend and manager. “If he had trained earlier and harder…”

“I beat lots of guys,” Durelle brags in retort. By his own count, he knocked out 223 of the 291 boxers he faced in his career. “And most of them, they didn’t fight again after I beat them.”

Whatever his boxing boasts, Durelle admits he was a loser at home during his career. He spent much of his time travelling to fights or training for fights and, when he did come back to Baie Ste. Anne for weekend visits, he would arrive with the entourage of managers, trainers, sparring partners and hangers-on who made him feel important. They would drink and laugh and shout until they left again on Monday morning. “Sometimes,” Therese sighs, “I remember wishing he wouldn’t come home at all when he was like that.”

Durelle says now he was simply too young. “I couldn’t settle myself down.” For much of the time his boxing career was at its height, he was also estranged from his children: “I’d come home and my kids would run away from me. They were scared of me. My own kids! I cried.” The four children, two boys and two girls, are all grown now and the family has made its peace. One of the boys is a welder in Fredericton, the other a policeman in Moncton. Neither ever wanted to be a boxer. “That was my doing,” Therese says forcefully. “It’s no life. Two grown men hitting each other. It’s crazy.”

“Ma’am,” Durelle says suddenly, as if he hadn’t heard her. “We got to call. Where’s the number?” Therese tells me resignedly the bill for long-distance calls to their daughters — one is a computer technician in Calgary, the other a mother and housewife in Yellowknife — runs to about $75 a month. Tonight, he talks with his daughter and granddaughter in Yellowknife. “Listen,” he says, holding the phone to my ear while three-year-old Jenny tells her grandfather what she wants Santa Claus to bring her. “She’s smart, that one. You listen.” The eyes are closed.

Therese brings out peanuts and potato chips and Yvon opens up some more beer. “Right now, Ma’am is the most important thing in my life,” he tells me. “If it weren’t for her, I’d be the worst hobo in the world.” Even in the worst of his best times, when he was ignoring family responsibilities for fistic fame and the good life, he would still occasionally remember how much he loved her. While training for the Moore fight, for example, he ran away from his training camp one weekend just so he could get back to Baie Ste. Anne to see her. Today, their relationship is bantering, warm. “No other woman in the world would put up with me,” he says.

Durelle is happy. He has the love of a good woman, children and grandchildren on whom he can lavish attention and, thanks to money he made from the sale of The Fisherman’s Club and reinvested, enough income to see him comfortably through his old age. He has good friends in Chatham who welcome him each morning when he shows up for coffee and, of course, the dog who is devoted only to him. Yvon Durelle is a happy man, but…

He is also bored. And he misses the times that are gone. The realization sneaks up on you like a punch from the blindside. In the flurry of his earnest efforts to convince you how happy he is today, he drops small hints: The disappointment in his face when he realizes there’s a fight in Halifax and he won’t be there, the need to exaggerate his already formidable achievements, the suggestions that I should arrange for a club in Halifax to invite him to show his film of the Moore fight. “They’d sell a lot of beer,” he says. “I know they would. People love to see that fight. They still love to talk to me.”

His fists brought him to that fight and the fight brought him, briefly, to the world. But other fists sent him home again and, today, fewer an

people remember what those fists could do. Tonight, all they can do is try to keep time with the music.

“Lie-La-Lie…”

We are listening to the end of that radio documentary about his career and Durelle is singing along with the theme music in a strange, high-pitched voice. The producers chose to end their tribute to him with “The Boxer,” a song by Simon and Garfunkel.

And a fighter by his tradeAnd he carries the reminders

Of ev’ry glove that laid him down

And cut him ’till he cried out

In his anger and his shame,

“I am leaving, I am leaving.

But the fighter still remains…*

“That was an old song, and they wrote new words-about me,” Yvon Durelle says. It isn’t true, but that doesn’t matter. The song is Yvon Durelle.

He picks it up again. “Lie-La-Lie…”

His eyes are closed.

*c 1968 Paul Simon.

ATLANTIC INSIGHT, DECEMBER 1982

TYvon

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

THE LATEST COMMENTS