Dr. Pamela Yates (Global)

This column originally appeared in the Halifax Examiner June 11, 2018.

Start with this: a July 11, 2017, CBC news story entitled “Lack of Psychologists Delays Youth Sentencing More than 6 Months.”

The story quoted Brandon Rolle, the managing lawyer at the youth office for Nova Scotia Legal Aid who pointed out that the IWK Health Centre was taking six to 13 months to complete court-ordered psychological assessments for young people guilty of criminal offences. Those assessments — a critical element in the youth justice process — should have been wrapped up in 60 to 90 days max.

The IWK, Atlantic Canada’s primary health care centre for children and youth, including those in trouble with the law, didn’t deny the reality. Instead, a spokesperson explained, “We have 3.25 psychologists available to us right now and they’re currently working overtime every week to get those reports.”

Assume for the moment the situation hasn’t improved all that much in the 11 months since that CBC report. Good assumption…

Now, flash backwards to 2014, three years before that CBC story appeared. That’s when the IWK posted a job opening for a “program lead” to run its Youth Forensic Services, Mental Health and Addictions program. At that point, the position had been vacant for three years.

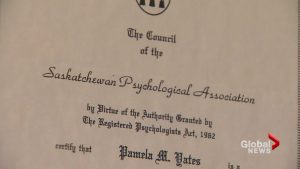

In Ottawa at the time, Pamela Yates, a prominent Canadian forensic psychologist, was considering what she would do in the next phase of her career. She was then the national director of reintegration services for Corrections Canada. She’d spent 18 years in the federal corrections bureaucracy, beginning as a psychologist in its regional assessment centre in British Columbia in 1997. The next year, she moved to Saskatchewan where she worked as a psychologist, then as clinical director for a sex offender program treating “the highest risk sex offenders in Canada.” By 2000, she’d moved east — and up — to Ottawa as national manager for all sex offender programs in the country, then served as director of a correctional program review, then director of planning and strategies, and then…

Those were heady times in corrections. The focus was on rehabilitation “and I was responsible for policy changes,” she says, adding proudly: “I worked with some heavy hitters.”

Then along came Stephen Harper and his Conservatives. Rehabilitation was no longer in vogue. Corrections Canada’s focus became lock-them-up-and-throw-away-the-key punishment and budget cutting.

Pamela Yates knew it was time for a change. She applied for two vacant positions: one at the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre, the other at the IWK. She was offered both.

Her husband’s family is based in Ottawa. He ran a business there. But he was ready to retire. Pamela had grown up in Halifax; her first degree — an honours BA in Psychology — was from Saint Mary’s University. “We were interested in a new adventure. We looked at the pros and cons and decided, ‘let’s have an adventure.’”

Although she’d spent much of her career on the policy side in the adult corrections system, Yates was not without clinical experiences in the field, or from the other side of the victim-perpetrator divide. While a grad student, she says she’d become “saturated, worn down” dealing just with prisoners, so she began spending time volunteering at women’s shelters in Ottawa, focusing on violence against women and children’s issues. “But ultimately,” she says now, “I decided I wanted to work with offenders. I wanted to do something, to get at the causes instead of just treating the effects.”

She saw the IWK job in that context. “I wanted to do for kids what I’d been doing in the adult world — to get to prevention. I felt I had 10-15 years left in my career and I wanted to make the IWK the centre” for young offender prevention and treatment.

More specifically, she believed she knew what needed to be done. “One of my projects,” she says today, “was to streamline the assessment process and reduce the time to complete assessments.”

But she adds she saw the IWK’s lack of psychologists as a “minor factor contributing to the delays… There were other services that also required attention. The youth sex offender program had an 18-month waiting list to complete an assessment, and treatment was almost non-existent… The majority of staff were not specialists in forensics, and so one of my responsibilities was also to increase their knowledge and skills in this specific area. With my background, I was to increase the number of youth served, reduce wait times and ensure the services offered were consistent with both young people’s needs and with best practices in the field.”

Yates moved back home to Halifax, settled in, got to work. Her early performance reviews were all positive. As were the results. The hospital’s youth forensic services team, she says, “was meeting deadlines except in all but a few of the most complex cases.”

And then, on August 7, 2015, she received a bolt-out-of-the-blue faxed letter from IWK vice president Jocelyn Vine: “This letter serves to inform you that your regular full-time position as the Clinical Program Leader, Youth Forensics, is being terminated effective immediately.”

What had happened?The short answer: the Nova Scotia Board of Examiners in Psychology, the all-powerful, self-regulating regulator of the psychology profession in the province, happened.

Soon after she’d begun her duties at the IWK, the board turned down Yates’ seemingly routine application to be formally registered as a psychologist in Nova Scotia, which was one of the official requirements of her new job.

“Your registration [as a psychologist with the College of Psychologists] in Saskatchewan is in the non-practising category,” board registrar Allan Wilson wrote. “You have never been fully registered as a psychologist in any Canadian jurisdiction… The board concluded,” concluded his letter of rejection, that Yates’ 25-years-in-the-past MA and PhD programs at Carleton had also focused too much on research and too little on applying research; did not require for-credit supervised internships; and included too few courses in assessment and evaluation, intervention, ethics and standards.

“It should be noted,” noted the letter in conclusion, “that failure to meet any one of the criteria can be sufficient for the board to conclude that the program is not acceptable.”

So… Concluded. Application rejected.

But…

It is true that, because she moved to Ottawa and worked more and more in management and policy, her licence to practise designation did become non-practising in 2005. To get it back, she would simply have had to put in more supervised hours, something she says she would have been happy to do, and told the board she would be happy to do.

The board didn’t offer her that option, in spite of the fact that, under a federal-provincial agreement on trade mobility and a mutual recognition agreement of the regulatory bodies for professional psychologists in Canada — not to forget the laws of common sense — the board should have been looking for ways to make it easier rather than harder for Yates to transfer her qualifications to needy Nova Scotia.

As for the board’s other arguments? According to Yates, the psychology education environment was very different in the 1990s. There were only three formal internship programs in the country, and only one of them was in her specialty of forensics. “I just didn’t even know that one existed,” she admits.

That said, she did spend three years during her “research-focused” grad program working as a “psychology intern” at the Rideau Correctional and Treatment Centre performing — among other duties — “direct intervention to incarcerated offenders with addictions and substance abuse issues.” Although that work was overseen by one of her MA supervisors as well as the Centre’s chief psychologist, it wasn’t for university credit “so it didn’t check that box” for the Nova Scotia licensing authorities.

Yates says she was “devastated” when the board rejected her application. “I was crying, but I was trying to be professional,” she says now. She called her boss, Dr. Ruth Carter, the then-director of mental health and addictions services at the hospital. Carter, Yates recalls, was “very supportive.”

The Nova Scotia Board of Examiners in Psychology’s internal review committee — which exists to provide an independent review of rejected applications — rubber-stamped the initial rejection. They did that despite additional submissions from Yates. She included:

- copies of three books she’d written on the assessment and treatment of sex offenders, including a guide for clinicians, which the registrar had returned unopened, without even presenting them to the committee.

- affidavits from her former PhD supervisor and a letter from a Canada Research Chair in Forensic Psychology who’d worked with her, all attesting to her skills and experience.

She even tracked down former students from her “research-focused” PhD and discovered that at least eight-to-10 of them were currently practising as psychologists in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, the Northwest Territories, Ontario and New Brunswick.

Yates applied for a judicial review of the board’s decision but —before she even got a response — the IWK had terminated her.

She was then turned down for the judicial review on the technicality that she’d waited too long to apply. So she went back to square one, applied again to the board for a licence in October 2016, was rejected again — “The board relies on its prior decision and will not be rendering a new decision as the matter has already been determined” — re-applied for a judicial review. And finally got her day in court.

In March 2018 — more than three years after she began her job at the IWK, close to two years after she was fired and less than one year after the CBC’s story on those delays in court-ordered assessments of young offenders — Nova Scotia Supreme Court Justice Timothy Gabriel released his decision, chastising the board of examiners for failing to follow its own act and for its “high-handed” procedural unfairness, and ordered the board to reconsider her application.

That process is apparently ongoing.

But the process that led us to this process raises all sorts of still unanswered — perhaps unasked — questions.

Why did the psychologists’ organization’s board of examiners reject Pamela Yates application in the first place? What is — what should be — its role in self-regulation of the psychology profession? Is there a pattern of self-protection in self-regulation by professional licensing bodies like the board of examiners that is less about protecting Nova Scotians and more about preserving its own professional fiefdom?

Consider this: the board of examiners claims it “protects the public by regulating practitioners of psychology in Nova Scotia.” Does that mean patients in Saskatchewan, where Yates was originally licenced (and could be again), are unprotected? How about patients in BC, the Northwest Territories, Ontario and New Brunswick, all jurisdictions where her fellow “un-interned” Carleton grads are now practising as psychologists? Should patients there be worried? Or should we?

There are also legitimate questions for the IWK. Why did it summarily fire Yates while she was still in the middle of her battle with the board of examiners to obtain her licence? Was that — again — to protect vulnerable patients from harm, or protect itself from criticism and liability?

As for Yates? She’s just finished up a contract with Dalhousie University to write a report on opioid addiction for Nova Scotia’s department of justice. She continues to run her own private consulting service training — among others — practising psychologists in risk assessment, treatment and management programs.

She says she’d like to stay in Nova Scotia, but she’s not sure she can afford to.

Meanwhile, it is worth noting that Yates’ position at the hospital — the one that was vacant for three years when arrived in 2014 — is still vacant today.

A version of this column originally appeared in the Halifax Examiner. To read the latest column, please subscribe.

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books