January 19, 2007

Denny’s Back in town

For Dennis Gerard Stephen Doherty, one-time fabulously successful singing star and all-time Nova Scotian-Irish free spirit, life had made a habit of spilling neatly and easily into its proper place without so much as a nudge from him.

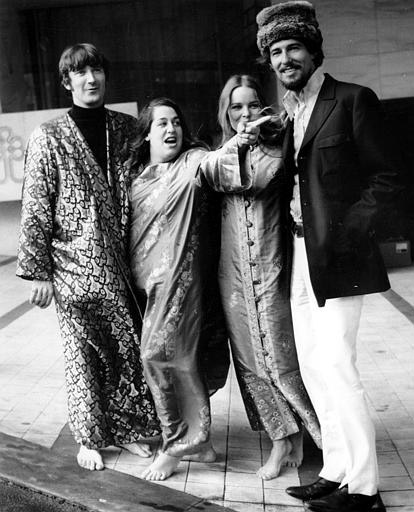

But by the spring of 1977, the last of the royalty cheques from his days with the Mamas and the Papas had disappeared into yet another good night and the California estate he had purchased at the height of his fame was decorated with a "for sale" sign. His friends were scattered — Mama Cass Elliot dead and Papa John and Mama Michelle Phillips, the husband-and-wife half of the group, puttering about in new careers and no longer husband and wife. For Papa Denny Doherty, California Dreamin’ had gradually become a dull, season-less reality.

So for no reason in particular, he decided it was time to go home. In Halifax, he spent some time with his father, drank a few drinks, and looked up some old friends. He performed at the annual Atlantic Folk Festival and waited to see what developed.

Across town, on the fourth floor of the CBC television studios, variety producer Jack O’Neil was all plans. Marg Osburne was gone and O’Neil needed another star for 13 half-hour shows scheduled for summer, 1978. He was sitting and doodling, and staring at his office wall when his musical director dropped by with a tape O’Neil just had to hear. It was from the Atlantic Folk Festival.

"The thing that hit me first wasn’t Denny’s singing," O’Neil recalls. "Everyone knew he could do that. What did impress me was a certain quality — a presence when he talked. There were 15,000 people at that festival and every one of them was listening when Denny spoke."

O’Neil quickly shipped the tape off to the head of network variety, Jack McAndrew, who pronounced himself "charmed" and swiftly signed Doherty up.

Without so much as a formal audition or even a word in his own behalf, Denny Doherty was the host of his own television series, Denny’s Sho* — a series that premiered last Thursday night and will be aired nationally in the same slot for the next 12 weeks. Breaks like that have been the story of his life.

"Listen, I’m up at the family homestead with the old man," he says on the phone. "Maybe we could all get together at Comeau’s and have a couple o’ beers."

A noisy, working-class bar plunked strategically across from Halifax’s Stadacona naval base, Comeau’s is the favorite haunt of off-duty sailors, taxi drivers, dockworkers and an over-the-hill gang of regulars who have long since staked out their own favorite tables. Denny’s father’s is the one nearest the main door.

This barn-like beer hall is light-years removed from the days when Doherty flitted from one exotic place to another in a hired Lear jet to be greeted by swooning pre-pubescents screaming, "Denny! Denny!" In Comeau’s, in fact, the better-known Doherty is his father — also Denny — a cheerfully grumpy retired dock-worker who still plays tuba for a local orchestra.

Denny junior gives no hint that he is bothered by the lack of attention paid him. A gold chain bracelet (“I wear it for the day I run out of gas in the middle of Idaho. I’ll just hack off a link and that’ll take me to L.A.") is the only physical leftover of his previous life. He has added a neat beard and a potbelly since the Mamas and the Papas split up and, with his heavy arms and stubby, working man’s hands, he looks like a dockworker on his day off. Which is probably what he would have become if it hadn’t been for music.

Born in 1940, the fourth of five children, he grew up in a clapboard, barracks-style apartment in Halifax’s hard-scrabble Wellington Court district. "Denny was always mummy’s favorite," says his father after ordering two glasses of draft beer all around. "In her eyes, he could do no wrong."

Denny, however, remembers differently….

Stories of his exploits begin to pour out faster than the beer. They all begin and end with the admonition that they must never, never be repeated. A mysterious fire in a lumberyard. An occasional smash-and-grab involving cartons of cigarettes. What saved him from serious run-ins with the law was music, more specifically, playing the trombone in the Police Boys Club band. "The cops would stop you and then they’d take a took and say, ‘Aren’t you the kid in the band?’ " Denny recalls, his green eyes flashing amusement. "They never knew what you had hidden in the bushes across the street."

An indifferent student, Denny fancied himself a singer. His friends eventually became so exasperated by his habit of singing along with the car radio that to shut him up, they finally dared him to get up and sing with the band at the Saturday night dances. Because his father knew the bandleader, Denny was given the chance to do a Pat Boone-like rendering of “Love Letters in the Sand” while 500 couples shuffled across the makeshift wooden floor that hid the usual ice of the Halifax Forum. "I could see that all those people were actually dancing and listening to me. I was hooked.” He was 15.

He soon drifted into fulltime folk music with a group called the Halifax Three. After a year of playing local clubs for drinks and change, they set off to make their fame and fortune. They arrived in New York at the beginning of the 1960s but, finding neither fame nor fortune, they went their separate ways.

Denny and the group’s backup guitarist, Zal Yanovsky (later a founding member of the Lovin’ Spoonful), headed for Mac’s Pipe and Drum in Washington where they waited tables, tended bar and, between sets of the featured attraction — a moonlighting bagpiper from the White House — got a chance to play and sing.

Between 1962 and 1963, he drifted in and out of half a dozen groups, and in late 1963, teamed up with John and Michelle Phillips to help complete a contracted series of concerts for a group called the New Journeymen. One crazy night at the end of the tour, with $6,000 in the group’s pockets and their heads full of LSD, John decided to spin Michelle around in front of a map of the world. Wherever her finger pointed when she stopped, he announced, was where the group would go. Her finger stuck on the Virgin Islands.

In a couple of days, nine adults, one child, a dog, four tents, two Yamaha motorcycles, a bull fiddle, a trombone, three guitars, a banjo, assorted suitcases and an American Express card were crammed aboard a flight for the Caribbean.

Once there, they spent their days on the beach at Cinnamon Bay, singing and playing "from sunup to exhaustion" for change from curious tourists. Originally, the singers were John, Michelle and Denny. Later they were joined by Cass Elliot, who had also flown down with the group but whose voice was considered not right for John’s demanding arrangements. Later, she was accidentally hit on the head by a copper pipe thrown from a second-floor window and thereafter was mysteriously able to reach the three high notes she’d been missing. Gradually their voices blended into a single, finely tuned instrument.

Eventually, the scruffy band of musicians attracted the interest of the governor’s bored nephew and thereby attracted the attention of the governor himself. He gave them 24 hours to get off his islands.

With their last $400 (a quick-thinking American Express clerk had already confiscated their credit card) they reached Puerto Rico, where they headed for the gambling casinos. "Michelle rolled 18 straight passes at the crap table and we were gone."

They took their music to Los Angeles but got no offers. The manager of the Kingston Trio suggested they try driving cabs. Capitol Records were polite but non-committal. Finally, Barry McGuire, an East Coast friend who’d made it big with a song called “Eve of Destruction” offered to help out by recording one of John’s songs with the four of them backing him up.

After the recording session was over and McGuire had left, the record producer, Lou Adler, could contain his enthusiasm no longer.

"Who have you talked to?" he wanted to know. "What do you want?"

Without missing a beat, John answered that they wanted "a steady flow of cash from your office to our house. We don’t have a house yet, and after you get that, we’ll need a car to get there."

Adler took care of all their needs, dropped McGuire’s voice from the tape and substituted Denny singing lead vocal. Nineteen weeks after it was recorded, “Calilfornia Dreamin’” became the biggest hit in Boston since “White Christmas.” It went on to be voted 1966’s record of the year by both leading U.S. trade papers. A second single, “Monday Monday” sold three million copies.

The Mamas and the Papas were suddenly very wealthy and very famous.

Doherty bought himself a Hollywood mansion once owned by Mary Astor, complete with Chippendale furniture, assorted knickknacks and all the trimmings. "I started a party there in 1966," he laughs, "and it lasted until 1969. I’d go somewhere and come back and it would still be going on." He gave away so much money that his business manager finally quit with the curt, apoplectic note: "I cannot handle your account anymore. You are crazy."

His father suddenly breaks in on this flood of profligate tales. "Everybody says Denny went wild with his money, but he did some good things too. He bought his mother a house, the first we’d ever had." His father still lives in that house. His mother died in 1970. "Put that in your story now. Don’t forget."

"’You don’t have to use that," Denny smiles, embarrassed.

But just as accidentally as the phenomenon of the Mamas and the Papas began, it was over. "We were supposed to play the Albert Hall and we went over to London in 1968. But when we got there, everyone took off in separate directions. I stayed in my hotel room for two weeks, then went back to California. We never played the Albert Hall. When everyone was back, we’d run into each other on the street and say, ‘See you Monday,’ but nobody ever said which Monday. There was no formal breakup. It just happened."

They resurfaced briefly in New York in a "wacky musical comedy" John had written, but the show opened and closed within a week. The play did give Denny a new-found love of acting — and a new love, a drama teacher named Jeanette who now lives with him in Dartmouth. An earlier, brief marriage in California produced a daughter who now spends summers in Nova Scotia.

But all his efforts to breathe new life into his musical career were abortive. Record company executives who had once grovelled for a piece of his time were "in conference" and couldn’t be disturbed when he tried to sell them on a rock’n’roll band he’d formed. His one solo album, produced by a fringe company, disappeared almost before it was released in a morass of bankruptcy and non-existent promotion.

He eventually fell into an acting job at the Irish Arts Center in New York but the centre was non-profit and the acting non-paying so, when the music money finally ran out, Denny Doherty figured it was time to come home. How many millions had he gone through by then? Denny says he didn’t keep count. Later, he says he’d rather not talk about that anyway since the U.S. Internal Revenue Service still has an interest in the group’s earnings.

Somewhere around the third round of beer, Denny and his father fall into an argument over how much time his father needs to rehearse before his planned appearance on Denny’s new television program — doing a tuba version of the old Beatles song, “When I’m 64.” “1 need at least two full days to practise," his father argues. "I’m not like you, you know. I do things right." Denny shakes his head in feigned exasperation.

Denny does in fact work hard when he’s in studio. For all that, he is genuinely not ambitious. There are still no real plans. And there are no regrets about days gone by, no chips on his chunky shoulders.

"Denny has this crazy, devil-may-care charm that I think is going to come across on television," Jack O’Neil says. “If the show takes off, his charm is going to be the reason. It’s the key to the show."

His father scowls indulgently into his beer. "You know, it sure is a good thing that boy can sing because, Lord knows, he can’t do anything else.”

I’ll drink that,” Denny grins. “May it last forever.”

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

STEPHEN KIMBER, a Professor of Journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax and co-founder of its MFA in Creative Nonfiction Program, is an award-winning writer, editor and broadcaster. He is the author of two novels and eight non-fiction books. Buy his books

THE LATEST COMMENTS